CHAPTER 7: Épater le Bourgeois: 1954–58

CHAPTER 8: “Working Perversely to Please Himself”: 1959–63

CHAPTER 9: Nursery Crimes— The Gashlycrumb Tinies and Other Outrages: 1963

CHAPTER 10: Worshipping in Balanchine’s Temple: 1964–67

CHAPTER 11: Mail Bonding—Collaborations: 1967–72

CHAPTER 12: Dracula: 1973–78

CHAPTER 13: Mystery!: 1979–85

CHAPTER 14: Strawberry Lane Forever: Cape Cod, 1985–2000

CHAPTER 15: Flapping Ankles, Crazed Teacups, and Other Entertainments

CHAPTER 16: “Awake in the Dark of Night Thinking Gorey Thoughts”

CHAPTER 17: The Curtain Falls

Notes

A Note on Sources

A Gorey Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Mark Dery

About the Publisher

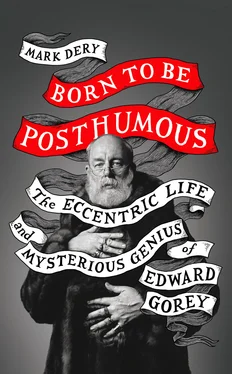

INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Cover Title Page Copyright Praise Dedication For Margot Mifflin, whose wild surmise—“What about a Gorey biography?”—begat this book. Without her unwavering support, generous beyond measure, it would have remained just that: a gleam in her eye. I owe her this—and more than tongue can tell. Introduction: A Good Mystery CHAPTER 1: A Suspiciously Normal Childhood: Chicago, 1925–44 CHAPTER 2: Mauve Sunsets: Dugway, 1944–46 CHAPTER 3: “Terribly Intellectual and Avant-Garde and All That Jazz”: Harvard, 1946–50 CHAPTER 4: Sacred Monsters: Cambridge, 1950–53 CHAPTER 5: “Like a Captive Balloon, Motionless Between Sky and Earth”: New York, 1953 CHAPTER 6: Hobbies Odd—Ballet, the Gotham Book Mart, Silent Film, Feuillade: 1953 CHAPTER 7: Épater le Bourgeois: 1954–58 CHAPTER 8: “Working Perversely to Please Himself”: 1959–63 CHAPTER 9: Nursery Crimes— The Gashlycrumb Tinies and Other Outrages: 1963 CHAPTER 10: Worshipping in Balanchine’s Temple: 1964–67 CHAPTER 11: Mail Bonding—Collaborations: 1967–72 CHAPTER 12: Dracula: 1973–78 CHAPTER 13: Mystery!: 1979–85 CHAPTER 14: Strawberry Lane Forever: Cape Cod, 1985–2000 CHAPTER 15: Flapping Ankles, Crazed Teacups, and Other Entertainments CHAPTER 16: “Awake in the Dark of Night Thinking Gorey Thoughts” CHAPTER 17: The Curtain Falls Notes A Note on Sources A Gorey Bibliography Index Acknowledgments About the Author Also by Mark Dery About the Publisher

A GOOD MYSTERY CONTENTS Cover Title Page Copyright Praise Dedication For Margot Mifflin, whose wild surmise—“What about a Gorey biography?”—begat this book. Without her unwavering support, generous beyond measure, it would have remained just that: a gleam in her eye. I owe her this—and more than tongue can tell. Introduction: A Good Mystery CHAPTER 1: A Suspiciously Normal Childhood: Chicago, 1925–44 CHAPTER 2: Mauve Sunsets: Dugway, 1944–46 CHAPTER 3: “Terribly Intellectual and Avant-Garde and All That Jazz”: Harvard, 1946–50 CHAPTER 4: Sacred Monsters: Cambridge, 1950–53 CHAPTER 5: “Like a Captive Balloon, Motionless Between Sky and Earth”: New York, 1953 CHAPTER 6: Hobbies Odd—Ballet, the Gotham Book Mart, Silent Film, Feuillade: 1953 CHAPTER 7: Épater le Bourgeois: 1954–58 CHAPTER 8: “Working Perversely to Please Himself”: 1959–63 CHAPTER 9: Nursery Crimes— The Gashlycrumb Tinies and Other Outrages: 1963 CHAPTER 10: Worshipping in Balanchine’s Temple: 1964–67 CHAPTER 11: Mail Bonding—Collaborations: 1967–72 CHAPTER 12: Dracula: 1973–78 CHAPTER 13: Mystery!: 1979–85 CHAPTER 14: Strawberry Lane Forever: Cape Cod, 1985–2000 CHAPTER 15: Flapping Ankles, Crazed Teacups, and Other Entertainments CHAPTER 16: “Awake in the Dark of Night Thinking Gorey Thoughts” CHAPTER 17: The Curtain Falls Notes A Note on Sources A Gorey Bibliography Index Acknowledgments About the Author Also by Mark Dery About the Publisher

Don Bachardy, Portrait of Edward Gorey (1974), graphite on paper. (Don Bachardy and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California. Image provided by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.)

Edward Gorey was born to be posthumous. After he died, struck down by a heart attack in 2000, a joke made the rounds among his fans: During his lifetime, most people assumed he was British, Victorian, and dead. Finally, at least one of the above was true.

In fact, he was born in Chicago in 1925. And although he was an ardent Anglophile, he never traveled in England, despite passing through the place on his one trip across the pond. He was, however, intrigued by death; it was his enduring theme. He returned to it time and again in his little picture books, deadpan accounts of murder, disaster, and discreet depravity with suitably disquieting titles: The Fatal Lozenge , The Evil Garden , The Hapless Child . Children are victims, more often than not, in Gorey stories: at its christening, a baby is drowned in the baptismal font; one hollow-eyed tyke dies of ennui; another is devoured by mice. The setting is unmistakably British, an atmosphere heightened by Gorey’s insistence on British spelling; the time is vaguely Victorian, Edwardian, and Jazz Age all at once. Cars start with cranks, music squawks out of gramophones, and boater-hatted men in Eton collars knock croquet balls around the lawn while sloe-eyed vamps look on.

Gorey wrote in verse, for the most part, in a style suggestive of a weirder Edward Lear or a curiouser Lewis Carroll. His point of view is comically jaundiced; his tone a kind of high-camp macabre. And those illustrations! Drawn in the six-by-seven-inch format of the published page, they’re a marvel of pen-and-ink draftsmanship: minutely detailed renderings of cobblestoned streets, no two cobbles alike; Victorian wallpaper writhing with serpentine patterns. Gorey’s machinelike cross-hatching would have been the envy of the nineteenth-century printmaker Gustave Doré or John Tenniel, illustrator of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. Hand-drawn antique engravings is what they are.

Gorey first blipped across the cultural radar in 1959, when the literary critic Edmund Wilson introduced New Yorker readers to his work. “I find that I cannot remember to have seen a single printed word about the books of Edward Gorey,” Wilson wrote, noting that the artist “has been working quite perversely to please himself, and has created a whole little world, equally amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned.” 1

That “little world” has won itself a mainstream cult (to put it oxymoronically). Millions know Gorey’s work without knowing it. Whether they noticed his name in the credits or not, Boomers and Gen-Xers who grew up with the PBS series Mystery! remember the dark whimsy of Gorey’s animated intro: the lady fainting dead away with a melodramatic wail; the sleuths tiptoeing through pea-soup fog; cocktail partiers feigning obliviousness while a stiff subsides in a lake. Then, too, every Tim Burton fan is a Gorey fan at heart. Burton owes Gorey a considerable debt, most obviously in his animated movies The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride . Likewise, the millions of kids who devoured A Series of Unfortunate Events, the young-adult mystery novels by Lemony Snicket, were seduced by a narrator whose arch persona was consciously modeled on Gorey’s. Daniel Handler—the man behind the nom de plume—calls it “the flâneur.” “When I was first writing A Series of Unfortunate Events,” he says, “I was wandering around everywhere saying, ‘I am a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey,’ and everyone said, ‘Who’s that?’ ” That was in 1999. “Now, everyone says, ‘That’s right, you are a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey!’”

Читать дальше