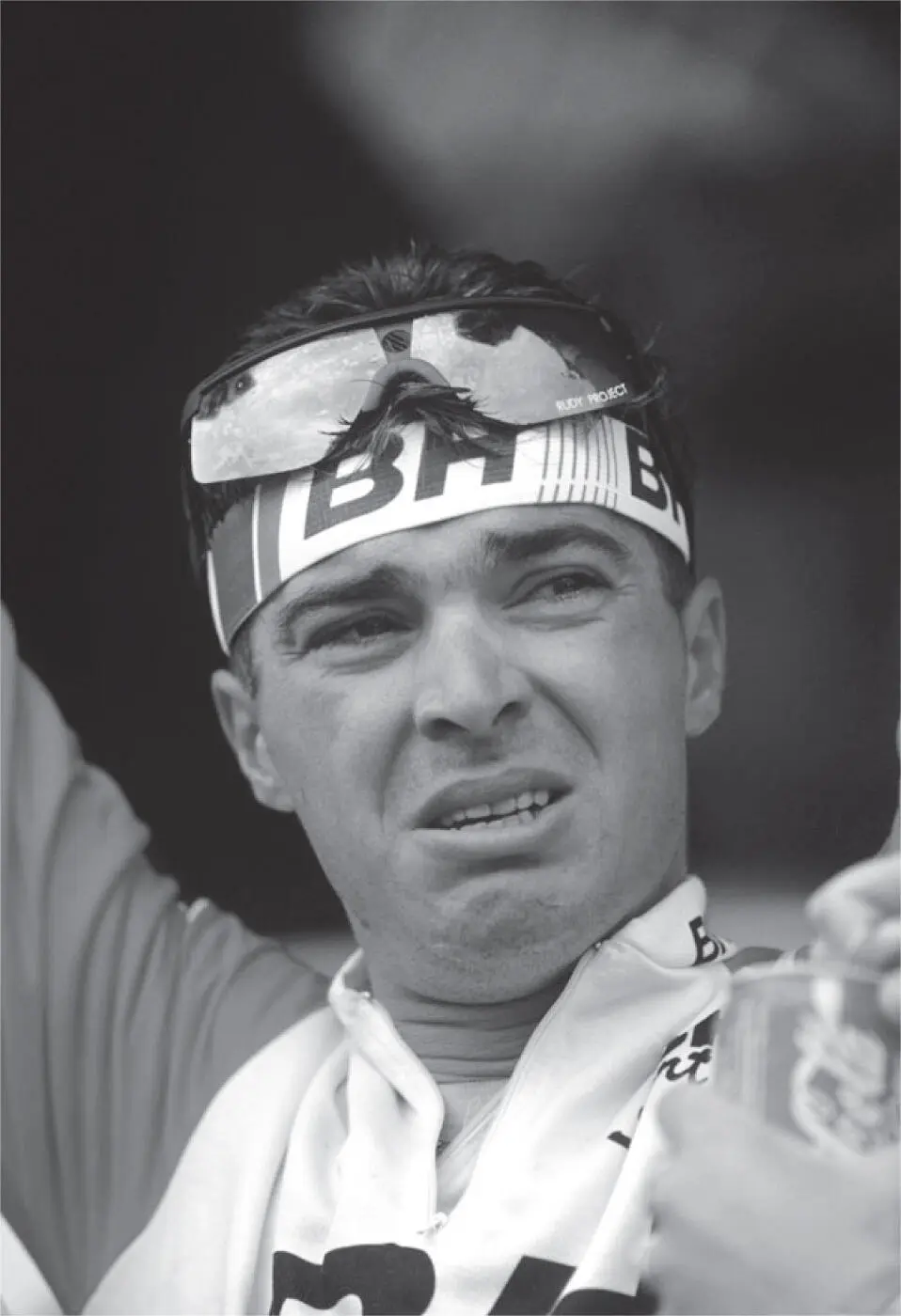

He is still regularly asked about Armentières. It is what he is remembered for. Which is ironic, because he still remembers nothing. ‘It has never come back. What I do remember now are the kilometres leading up to the finish. A lot of twisting and turning. Very fast. But the fall … nothing.

‘My first memory is waking up in the hospital. I had no idea what had happened. I knew – because I was hospitalised – that something had happened to me. But I couldn’t figure out what it was exactly. I had no broken bones or anything like that. How? Why? I had no idea. In the early morning, people started coming in, but I didn’t really speak French back then. So it was still a bit unclear. There was a television in the hospital that you had to keep going by putting coins in it. Believe it or not, that started showing the images of the race, and just when the sprint was about to happen I ran out of money! So even then I didn’t see the crash.

‘I didn’t see Jalabert in the hospital. I saw a man on a stretcher, but had no idea it was Jalabert. I just saw a lot of blood.’

Nelissen didn’t see the policeman, either. Nor did he hear from him. In his interview with Truyers in the winter of 1994, Nelissen said: ‘People say he was given a camera by a girl behind the barrier and he took the picture to do her a favour.’ Even if that were true – and it was never proven – Nelissen remarked that it was ‘very sweet of him, but not allowed. He was there to secure our safety, which didn’t happen.

‘It’s unfortunate, but he didn’t do it deliberately. Therefore I didn’t want to press charges, even though there was a lot of pressure from the team. That would just have caused a lot of misery and pain. For him, it would have been terrible; he would have lost his job, his house. That, I would have never wanted. I don’t want him to pay for the rest of his life.’

Gendron, the gendarme, worked for the French army unit CRS-3 in Quincy-sous-Sénart, though Nelissen understood that he moved – or was moved, perhaps – to the south of France with his wife and young child after the incident. The crash in Armentières was the subject of a subsequent police investigation, but Gendron was cleared of any wrongdoing.

At the time, would Nelissen have wanted to see him? ‘Huh,’ he says. ‘An apology would have been nice … I did hear stories later on that he lost his house … But what do you make of stories like that?’

Peter Post estimated that the cost to Nelissen in lost earnings was around £2 million. And although, as Nelissen told Truyers, the rider did not want to pursue Gendron through the courts, Post felt differently. ‘Peter Post didn’t want to leave it,’ Nelissen says now. ‘But what happened in court exactly, I don’t know. I personally got 65,000 Belgian Francs [about 1,500 Euros]. That’s what the policeman had to pay me. But what he had to pay to Peter Post, to the team, I don’t know. There was a legal case; I had to deposit my [medical] expenses, my bills. But I never appeared in court. I was just given this compensation.’

Nelissen recalls that he was back on his bike just two weeks after the crash. Really, he says, his injuries were not that bad. It was a miracle. It could also be partly why he harbours no ill feeling towards the policeman. On the contrary, he is remarkably generous. ‘If you hear what happened, that he took a picture for a little child,’ he says now, ‘well, everybody makes mistakes in life. He has been punished very hard for it. But I don’t really know what happened to him; I heard so many stories, it’s impossible for me to figure out what is true and what is not.’

The legacy of the crash for Nelissen is a scar above his eye and problems with his back: ‘I had three hernias that go back to the crash. My spine was damaged, but the helmet took the blow, that’s for sure. You need some luck in life.’ But he is known for his bad luck. ‘Yeah, but I was still lucky in a way. It could have been worse. That’s how I see it. I can be grateful for still being here. After my last accident [at Ghent–Wevelgem], I’m lucky to still have a right leg.

‘People have often told me I was born unlucky, but that’s not how I see it. The young rider in the Tour [Fabio Casartelli, who died in a crash in 1995], then [Andrei] Kivilev [who died in a crash in 2003], these riders didn’t have my luck. I have to see the positive.’

He still follows the sport, he says. But he doesn’t ride a bike. ‘Let me put it this way: if I do ride on two wheels, it’s on a motorbike. Nothing else. I drive a Harley-Davidson now, which I bought last year. I had one before, but now I changed it for a heavier model. A bit easier, more comfortable. Bike riding, no. No time and no motivation.’

And no fear of speed? ‘No, not at all. But I know the dangers of riding on two wheels. I take everything into account: rain, road surface, if there are small stones … I try to anticipate, because that’s when it’s dangerous. If you’ve ridden on two wheels so many times in the past, and you’ve fallen so many times, then you know what can happen.’

Nelissen appears content. The only experience that can induce anxiety is the place itself: Armentières. ‘I still get goosebumps when I pass through that neighbourhood. Which happens quite often, riding home from Calais. Same for Lovendegem [where he crashed at Ghent–Wevelgem]; you realise, this is where I fell. Lovendegem is worse, because that was fin de carrière . When I enter that town now, it’s strange. I deliver there, so I am there often. It’s not fear, just a strange feeling. This is where it all turned into shit.’

Armentières doesn’t quite hold the same memories. As Nelissen puts it: ‘There is nothing for me to forget, because I don’t remember anything.’

Classement

1Djamolidine Abdoujaparov, Uzbekistan, Polti, 5 hours, 46 minutes, 16 secs

2Olaf Ludwig, Germany, Panasonic, same time

3Johan Museeuw, Belgium, Mapei, s.t.

4Silvio Martinello, Italy, Mercatone Uno, s.t.

5Andrei Tchmil, Russia, Lotto, s.t.

6Ján Svorada, Czech, Lampre, s.t.

Joël Pelier

7 July 1989. Stage Six: Rennes to Futuroscope.

259km. Flat.

On the morning of the first road stage of the 1989 Tour de France, Joël Pelier told his team director, Javier Mínguez: ‘I would like to attack today.’

‘Joël, you know why you’re paid,’ Mínguez replied. ‘To protect Cubino.’

‘I was an équipier ,’ Pelier explains, ‘so I worked for my team leader.’ Laudelino Cubino was a typical Spanish climber. ‘Forty kilogrammes soaking wet and he couldn’t ride at 60kph on the flat. I was his guardian angel.

‘When you’re an équipier ,’ Pelier continues, ‘you don’t have any possibilities for yourself.’ But five days later, during stage six, Mínguez had a change of heart. ‘I don’t know why,’ Pelier says, ‘but he gave me carte blanche . During the stage, I went back to the car to get a rain jacket and bidons . There were about 180km left, and he asked me why I didn’t attack. It was like he was challenging me. He told me he didn’t think I had the balls to attack because there were too many kilometres left. He was laughing, but it was like a bet, or a challenge.’

Читать дальше