On my return, my mother and I discussed the visit and she insisted that I really think about what I wanted to do. ‘Mike, I hope you’re not doing this for me or your father, because that would not be right. If you don’t want to go, then please tell me, and that will be the end of it.’ When I told her I wanted to stay at home she said, ‘Good, that’s that, then.’

We never spoke about it again until many years later when she confided she was thrilled with my decision, as she dreaded the prospect of me living away from home at such an early age. Crucially, though, she reiterated that she would have supported me either way. Mum and Dad often pointed out possible obstacles but never ever put one in our way.

As a young teen I was a true believer, and very dedicated to the Catholic Church. I spent a lot of time as an altar boy in the local Friary. It was a beautiful place and most of the Franciscans were wonderful people. We had many visiting priests and brothers who came to spend time at the centre, and when I was about fourteen, maybe fifteen, a regular visiting Franciscan brother came to our house to ask my mother for permission to take me to Galway for a weekend retreat. He sat with my mother and grandmother drinking tea, talking God and Church and praising my work at the Friary. He blessed them both and followed me out to the hallway, closing the door behind him. In the privacy of the hallway he enquired about my girlfriends, their names and which one I liked best. He began poking and feeling around my genital area, asking me if I liked it. I felt trapped, and was extremely uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to do. He continued until I managed to get to the front door. I begged him to leave me alone. As he pushed past, I noticed a lot of dandruff on the collar of his brown robe. That’s how I still remember him today. I felt ashamed, and almost dirty. I made up some excuse for turning down the trip to Galway, and I left it there in that hallway for years and years and tried not to think about it. Years later, I was walking down Abbey Street in Dublin when I spotted him coming towards me. I panicked, and hid in a doorway. As he walked by, all I noticed was the dandruff. It was still there. I wanted to scream at him, but I had no voice. I was still scared, or perhaps ashamed. I was twenty-one years of age. I never saw him again.

We all knew that certain priests in the parish were ‘dodgy’ – many altar boys relayed stories of hands slipping into their trousers. Some of us eleven- or twelve-year-olds were once brought into the office one by one by a Franciscan priest, who said he was to show us some ‘personal hygiene’ habits. He said our parents had requested it, but that we were bound to silence, as they were far too embarrassed to broach the subject further. Best keep it to ourselves. Yes, Father. Among ourselves we knew there was something wrong. We had our names for them, and we tried to steer clear of their advances and warn the younger boys, but the overriding reality was that we had a dedication to a church that controlled every aspect of our lives – and that’s where their power lay.

I have never forgotten those instances of abuse, and unfortunately to this day I still harbour a deep sense of personal responsibility for allowing them to have occurred in the first place. I have had to wrestle with that guilt every time it finds its way to the surface. I certainly felt betrayed. Thankfully, I do not own that shame any more. Healing is powerful in that regard.

In 2001 I felt compelled to write and record a song called ‘Garden of Roses’ after all the harrowing accounts of cases of child abuse by religious orders, including one particular cleric close to home. Deep down I knew I had to speak to Mum about the song’s imminent release, and if I could, talk about my own experience. Words will never truly describe that profound moment between a mother and her son. We talked and cried a little but together crossed over into a very special place of understanding. I felt such a deep sense of relief because I knew she understood my hurt, and I in turn empathised with her own very personal pain.

In the garden of roses where you came by,

Beautiful roses, the eyes of a child

In your secret desire you cut it all down.

Now the petals lay scattered on tainted ground

In the garden of roses, beautiful roses.

Hot Press founder Jackie Hayden called me after hearing the song; he wanted permission to include it in his book In Their Own Words , a compilation of personal stories from abuse victims in the Wexford region to support the Wexford Rape Crisis Centre. I was invited to perform at a few very powerful and moving healing services where the song found its true home. The song continued to make an impression with listeners as the revelations kept coming, as it was included in a 2011 book, The Rose and the Thorn by Audrey Healy and Don Mullan. In the autumn of 2018, I was invited to perform the song once again, but this time at a day of remembrance for Ireland’s lost children at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam in County Galway. It seems we have come some way from those terrible days of darkness. I certainly hope so. May the healing continue.

Now your temple has fallen, the walls cave in.

We witness the sanctum in their evil sin.

But a river once frozen deep in the mind

Flows on like a river should in the eyes of a child

In the garden of roses, those beautiful roses.

– ‘ Garden of Roses’, What You Know (2002)

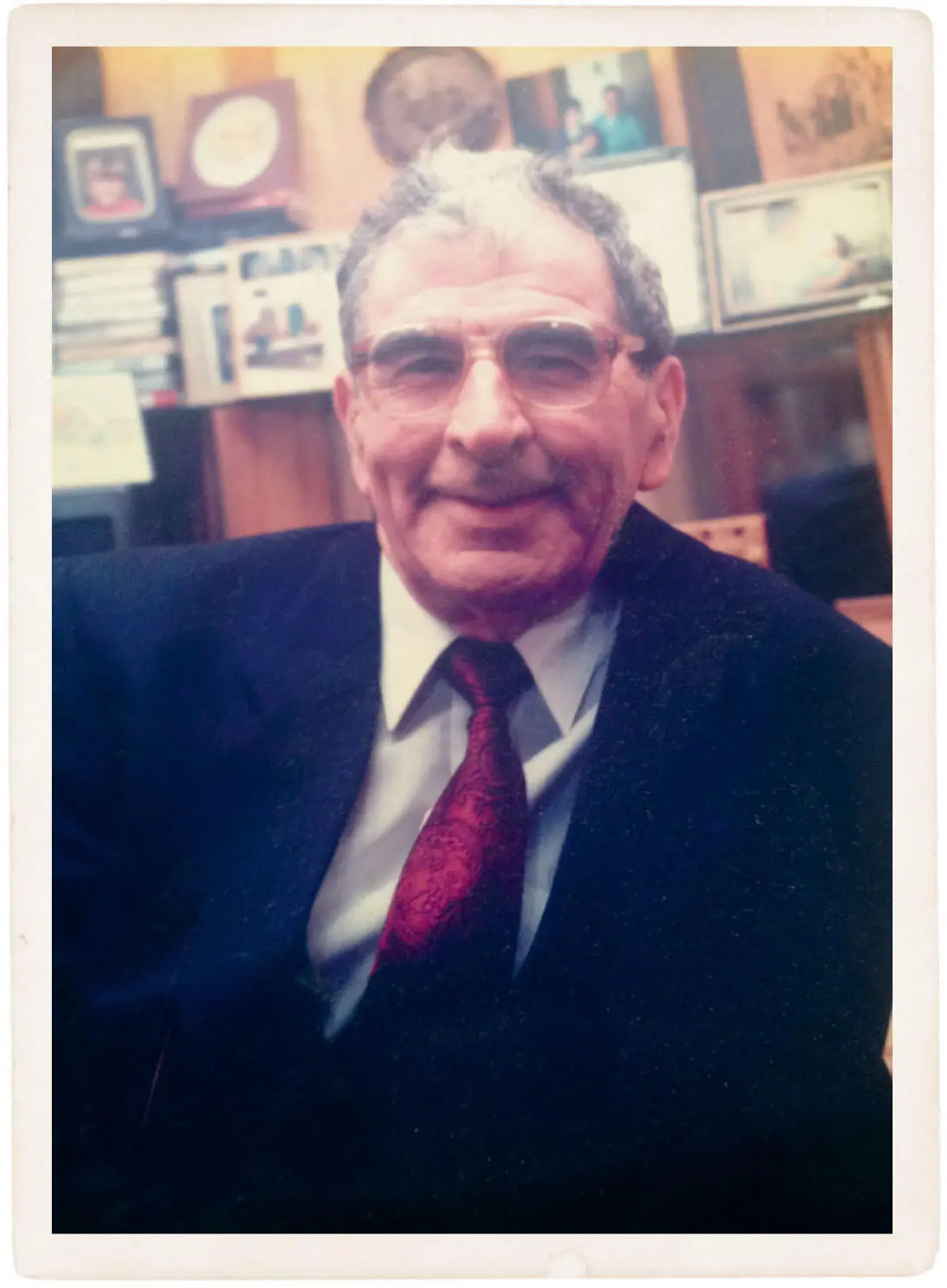

FAREWELL TO DAD

My dad died before the avalanche of abuse stories arrived, and I know he would have been shocked to the core. He was a very religious man, and like many of his generation lived by church rules and served without question. I have no doubt that I could have spoken openly to him about writing ‘Garden of Roses’. He would have listened and offered comfort, of that I am certain. His death in June 2000 had a profound effect on my life and my songwriting. Two years later I released the album What You Know . The title of the album is an expression he used for almost everything that he could not instantly put a name to. If he wanted you to get a paintbrush from the shed he might say, ‘Mikie, will you get the what-you-know from the shed, I want to finish that bit of painting. It’s in the box beside the what-you-know, the screwdrivers.’ You had to be on his wavelength, but we usually were.

A songwriter friend of mine once wrote of his dad’s passing, ‘The greatest man I never knew lived down the hall.’ It was such a sad song. I am glad to say I knew mine very well and we shared many great times together. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he was given nine weeks to live. Such was his strength and determination he lasted almost two years and faced it with great courage. Thankfully, I never had a slate to clean with him so we carried on as normal and tried our best to make the journey comfortable. His funeral was one of the biggest Ennis has ever seen, a testament to his wonderful personality and selfless generosity. He sits on my shoulder for every gig and I love to talk about him. He never got to see me in chef whites but I have absolutely no doubt it would have pleased him and he may have turned to Mum and said, ‘Sure, Mary, once he has a frying pan in his hand, he won’t go hungry.’

Take away the sad and lonely, all the trouble that surrounds him,

Firefighter won’t you come …

CHAPTER 2

DOOLIN

Читать дальше