Copyright

For Dan, with love

Each of these modern stories is a variation (a very free one) on a much older tale.

The original fables are summarised at the end of the book.

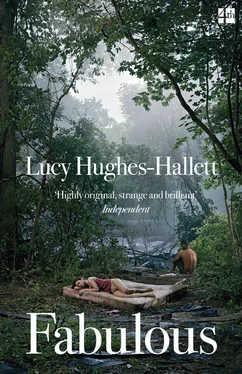

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Author’s Note

6 Contents

7 ORPHEUS

8 ACTAEON

9 PSYCHE

10 PASIPHAE

11 JOSEPH

12 MARY MAGDALEN

13 TRISTAN

14 PIPER

15 The Fables

16 By the Same Author

17 About the Author

18 About the Publisher

Landmarks CoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pages iii iv v vii 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 21 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 47 50 51525354555657585960616263646566 69727374757677787980818283848586878889909192939495 97100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115 117120121122123124125126127128129130131 133136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158 161164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197 199201202203204205 ii 207

There was no forewarning.

She was in the park with her friend.

Every Wednesday they went, with their dogs. ‘What do you say to each other?’ he asked. She couldn’t answer. But he knew that they talked all the way round.

Once he went looking for them. There was something he was worried about. Something that couldn’t wait until she got back, at least that’s what he thought. He saw them coming towards him between the silver birches and she was talking, hands in the pockets of her old velvet coat, head down watching her feet, talking non-stop. When she looked up and saw him she waved, and after that it was her friend who was talking, looking at him, as she did so, in a way he thought rude. When they came up to him he explained about the thing. Was it the heating? He wanted her to hurry home with him, but she didn’t seem to care about it. She wasn’t a worrier the way he was. Sometimes he found her insouciance maddening.

Anyway, that was a while ago. But then she was out with her friend again and the earth cracked open and an arm reached up from the chasm and dragged her down.

The friend, she was called Milla, came and rang the doorbell. He could hear her over the intercom but he couldn’t understand what she was saying. He could have just pressed the little button, but he didn’t want her coming in for some reason – he’d get annoyed with Milla, the way she was always wanting his wife to go out with her and leave him on his own – so he took his keys like he always did, in case, and went down the stairs quite slowly. Through the stained glass he could see Milla jerking around, and he could hear the bell ringing and ringing upstairs in the flat. He opened the front door. He’d probably been asleep. That would be why he hadn’t noticed she was late back, and why he wasn’t sensible enough to let Milla in with the little knob.

Milla said, ‘Oz, I’m so sorry. Oz, Eurydice’s … She’s in St Mary’s. I’ll take you. Let’s go and get your coat.’

The terrible arm dragged Eurydice out of the light. She, who had always slept with a lamp left on in the corridor because darkness pressed against her eyes and smothered her sight. She, who would fuss about restaurant tables, who always wanted the one by the window. She, who would shift her chair around the room throughout the day, dragging it six inches at a time to be always in the patch of sunlight. She sank into blackness. She was obliterated.

Milla didn’t see it happen. Oz saw it as they drove to the hospital. He saw it over and over again. He saw the hand slipping itself around Eurydice’s knees as a snake might wrap itself around its prey. He saw it descend on her from above and lift her by her hair so that the skin of her gentle face was pulled tight over sharp bones. He saw it grasp her around the hips and heave her up, head and feet flopping down undignified. Fee Fi Fo Fum and down she goes. Into the crevasse she went, into the valley of death, into the foul mouth.

Where is she? He kept asking and asking. Milla was patient with him. Milla said, ‘She’s in St Mary’s. We’re on our way there. We’ll see her very soon.’ ‘I know, Oz, I do too, but the doctors are with her. We just have to sit and wait.’ ‘I don’t know how long, but the nurse will tell us as soon as she can.’ ‘I’ll get you a cup of tea, shall I?’ ‘Don’t drink it yet, it’ll be hot.’ ‘I’ll wait outside. Here. This gentleman will help you.’ ‘She’s in the Greenaway Ward. We’ll see her in a minute or two.’ ‘In here.’ ‘She’s here, Oz. Look. Here she is.’ But Eurydice was gone.

What had been left lying among the pliable blades of coming daffodils was something as frail and pretty and futile as the feathers from a plucked bird. He was grateful to Milla for caring so much about it. He knew she was right – the conventions governing human civilisation required them to pick the remnant up, and rush to find help for it, and keep watch by it – but it was no longer Eurydice, no longer his wife. He saw the hands, dry and pale, with the tiny wart at the base of the third finger on the right, and her grandmother’s pearl ring on the middle finger on the left, and the broken nail she had complained about as she was putting on her scarf to go out that morning and the nail caught in the woolly stuff. They were her hands, but she had left them, along with her thinning hair and scaly elbows (I’m like an old tortoise, she said, when she felt them) and the ankles which still, when she wore black tights or even more when she was bare legged in summer, were worth showing off. These things had been hers, but they failed to contain her, to keep her safe.

Gluck has him singing at the moment of loss. A lament, generalising from the particular, meditating upon lovelessness and how it annuls life’s meaning. Stuff like that. Monteverdi was wiser. Monteverdi asks him only to sing a word that is barely a word even. ‘ Ahimè ’. A sigh. A sigh which brings the lips together, which says mmmm’s the word from now on for evermore, and then relents into that plangently accented vowel.

He had a remarkable counter-tenor voice. The critics said Suave Silvery Ethereal Limpid. When he was young he was afraid women would think he was gay, or weird, because his voice was as ungendered as an angel’s, but he needn’t have worried.

All that afternoon he sang. He felt too shaky to stand but his powerful lungs drew in air and converted it into music. He was a clarion. Milla tried to hush him but he didn’t even know that he was singing, so how was he to know that he should stop? They gave him a chair and placed him by the bed where they said Eurydice was lying, but she wasn’t there.

He could see her neck, and the softly puckered skin where it met her shoulders. He knew that part of her so well – so well – but this afternoon it was no longer hers. She’d left it behind, as she left clean hankies in the pocket of his coat when she borrowed it. Her favourite mug, the colour of violets, upturned by the sink. Clues as to her presence. He tried to tell one of the nurses how touched he was to see that piece of her neck, how much it reminded him of her, but the nurse thought he was worried that she might be cold, and pulled up the blue blanket so that even that memento of her was hidden from him.

Читать дальше