On 18 March, 1967, the Torrey Canyon ran on to the Seven Stones Reef and in all about 60,000 tons of crude oil were lost into the sea. At least 10,000 birds were collected, and many more must have died unbeknown, of which 9 out of 10 were guillemots. In the aftermath we now know (see special review by Bourne 1970, and Parslow 1967) that guillemots at some breeding colonies in Scilly and the north Cornish coast have been considerably reduced; in Cornwall, but not Scilly, fewer shags and herring gulls were breeding in 1966; kittiwake numbers at a colony within the worst polluted area were reduced in 1966. Only a few razorbills and apparently no puffins suffered in Britain, though these last are difficult to census. This was not the case in the Sept Iles in Britanny, the most important seabird colony in France, where careful protection had allowed a recovery in seabird numbers following the persecutions of the last century. While aerial species such as the gannet had escaped damage, such divers as the shag had suffered markedly and the auks very severely: counts before and after the incident show that the number of pairs of guillemots fell from 270 to 50, of razorbills from 450 to 50, and of puffins from 2,500 to 400. This is the first incident where really detailed knowledge has been available, making a fairly comprehensive ecological survey possible so that wildlife interests are given more than passing regard. The public has been aroused at the prospects of ruined beaches and the ‘overriding concern of the Government throughout has been to preserve the coasts from oil pollution and to adopt a course most likely to achieve this end’. Unfortunately the enormous quantities of detergents used for this purpose have done vastly more immediate and probably long-term harm to intertidal organisms than the oil itself. Whatever the pros and cons of the whole sad story, it illustrates the dilemma man finds himself in today. In some fields his technology has progressed far too quickly, while in others it has lagged, so that when accidents occur he is too often forced to resort to ill-conceived panic measures. Since this book has been in press there has been another major wreck of auks, this time in the Irish Sea in August 1969. At first attributed to gales, it seems that many birds came ashore under conditions of not particularly unfavourable weather. Analyses show the bodies to contain high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls, agents used in the paints and plastics industry. This new chemical hazard, unrealised when Mellanby prepared his book, highlights the complexity of the interaction of man and wildlife and the need for drastic measures if man is to avoid becoming the ultimate victim of this extensive environmental pollution, which wildlife is indicating.

CHAPTER 2

ECOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

A THOROUGH insight into the relationships between birds and humans demands some understanding of population ecology, a knowledge of how animal numbers fluctuate and change through births and deaths and of the factors which determine these processes. Populations have dynamic properties and these cannot be neglected by people concerned with wild life management, whether as game preservers, conservationists, pest controllers or farmers. This chapter attempts to set out some of the basic principles with pertinent examples, but these same principles will emerge in later sections in various guises. Our knowledge of the subject was first collated and clearly enumerated by Dr D. Lack (1954) in a stimulating book The Natural Regulation of Animal Numbers since when more field studies have been made by various workers, which Lack (1966) has summarised in his Population Studies of Birds. Both books should be consulted by the reader who is really interested in this subject. In this account I have drawn on examples which, wherever possible, have direct relevance to economic ornithology.

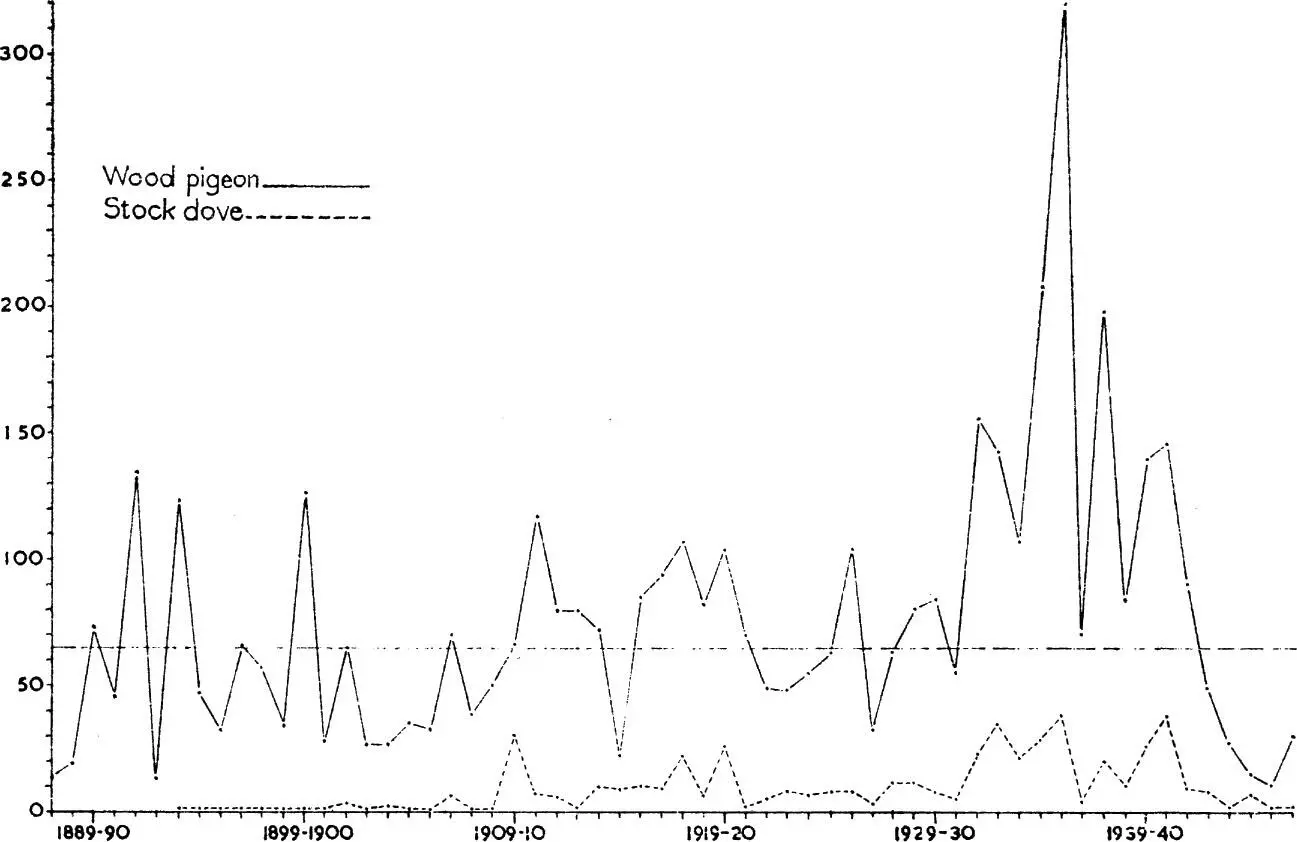

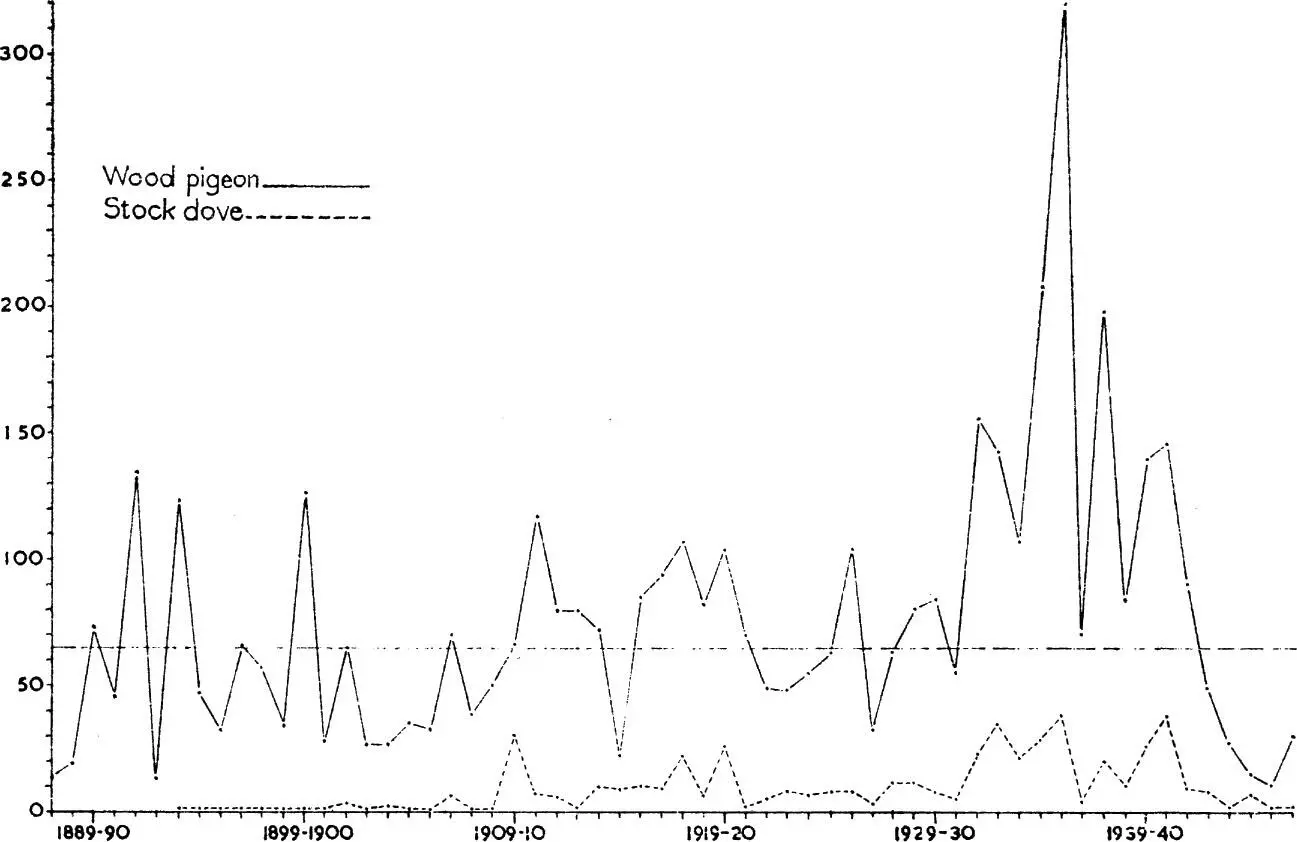

Farmers tend to the pessimistic belief that all problem birds become more abundant every year. Yet careful counts of most such species living in stable environments usually show there to be no clear tendency towards a steady increase, or even decrease, though numbers may fluctuate from year to year. For instance, many farmers believe that the wood-pigeon has increased drastically during this century to become more of a pest, though in conditions of stable agriculture this is unlikely to be true. In fact, there is evidence of a decline since the early 1960s associated with a reduction in the acreage of winter clover-leys and pastures. Certainly the species has moved into newly developed marginal land; places like the east Suffolk heathlands, which have been ploughed and claimed for agriculture since the Second World War, have been colonised by wood-pigeons. Fig. 1 gives some indication of how wood-pigeon numbers have varied on a Scottish estate near Dundee since 1887, and it is evident that fluctuations have occurred within narrow limits, with no evidence at all for a sustained rise or fall. In contrast, Fig. 1 also shows how the closely related stock dove has increased over the same period; this species first colonised in Scotland in 1866, reached Fife in 1878 and increased dramatically in Scotland in the next ten years. Every year each pair of wood-pigeons rears on average just over two young and it is evident that if all these survived to breed in their turn, population size would increase exponentially. That this does not normally occur indicates that some form of regulatory mechanism must be operating. Furthermore, this regulation must be density-dependent, that is, it must become proportionately more effective at high population densities and proportionately less effective at low ones. If the regulatory factor (s) operated without regard to density, it is evident that population size could fluctuate widely without reference to a particular level – to the constant mean represented by the dotted line in the figure.

FIG. 1. Annual number of wood-pigeons and stock doves shot on an estate near Dundee. The data refer to an area which remained virtually unchanged during the period under review, and nearly all the birds were shot by one man who maintained a reasonably constant shooting pressure. They, therefore, probably provide a fair index of the total population. The autumn of 1909 was a disastrous one for the harvest owing to gales and rain from August until October so that much corn remained uncut. This resulted in an influx of wood-pigeons and the appearance of stock doves in large numbers. (Data by courtesy of Dr J. Berry.)

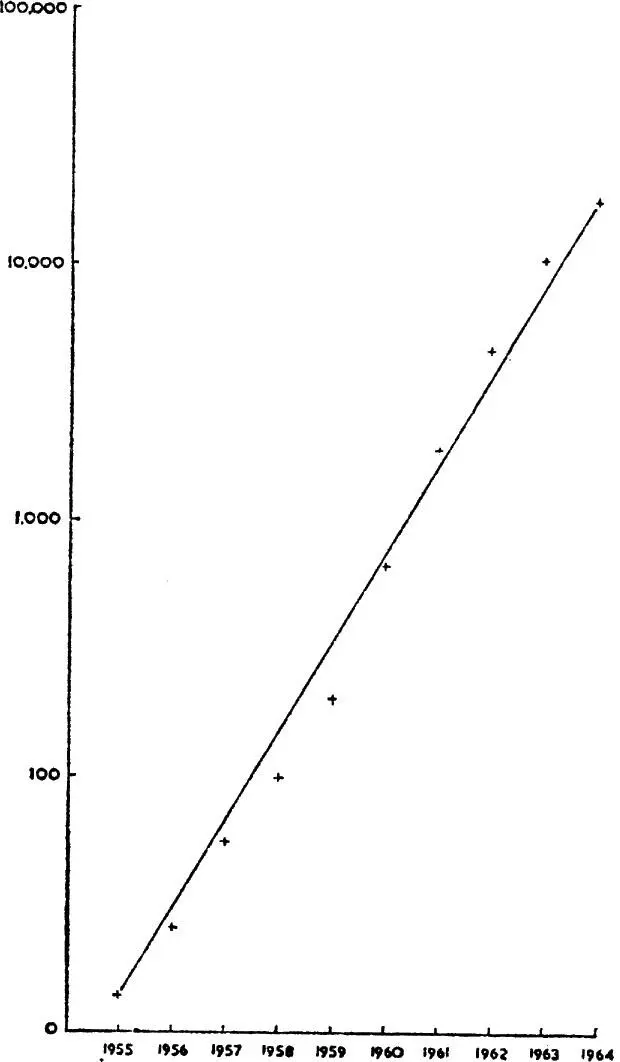

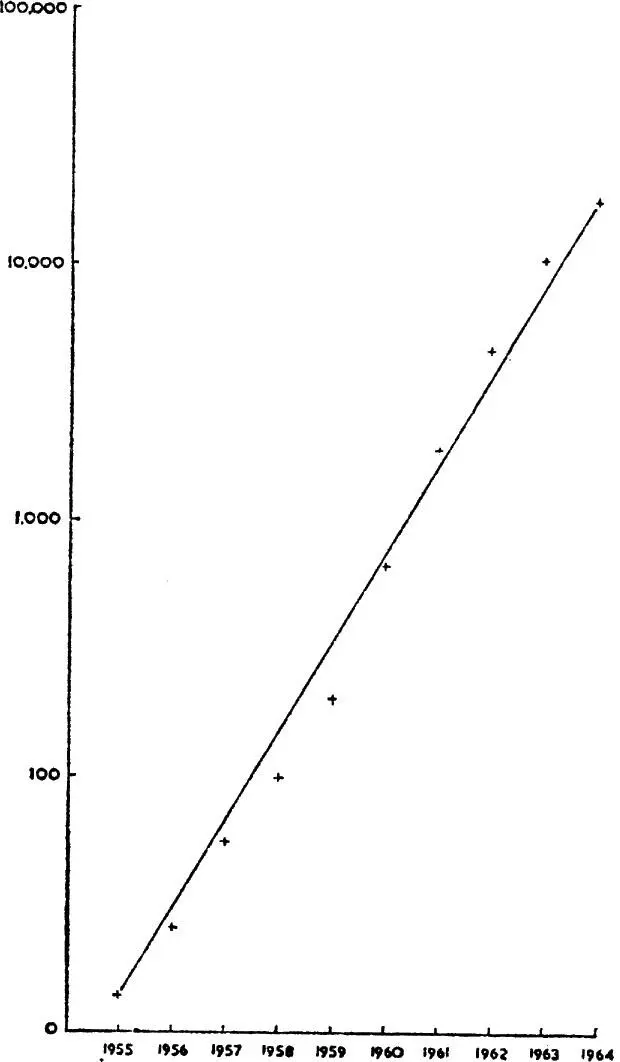

FIG. 2. Logarithmic increase of the collared dove in Britain. (Data from Hudson 1965).

Sometimes bird numbers do in fact increase geometrically, as when a species moves into a previously untenanted region where there is scope for it to live; in biological terms where a vacant niche exists (see below). In this way the collared dove dispersed dramatically across Europe to reach Britain in 1952. It had spread to south-east Europe from northern India by the sixteenth century but had then remained static in its European outpost until 1930. It has subsequently spread north-west across Europe, reaching Jutland in 1950 and Britain in 1955; an expansion 1,000 miles across Europe in twenty-four years. Why this spread was so long delayed is not clear, though it is most feasible, as Mayr has suggested, that a genetical mutation occurred which suddenly rendered the species less restricted in its needs. (We can imagine a bird, though not necessarily the collared dove, to be restricted by a temperature tolerance which a single sudden genetic mutation could remedy.) Throughout Britain and Europe a vacant niche existed for a small dove living close to man; it is even possible that the decline in popularity of the dove-cote pigeon created this niche. Whatever the explanation, a high survival rate among collared doves has evidently been possible, and their potential capacity for geometric increase has been realised: see Fig. 2, which relates to Britain. The Syrian woodpecker may be on the brink of a similar explosion. It is considered to be a recently evolved species (post-glacial) which replaces the great spotted woodpecker in south-east Asia. It spread to Bulgaria to breed in 1890, to Hungary in 1949 and to Vienna in 1951. A significant feature of the bird’s ecology in Europe is its confinement to cultivated areas which do not suit the great spotted woodpecker. If it proves to be better adapted to this man-made niche we can anticipate a continuing advance across Europe. Agricultural development in the Balkans may well bring other surprising range extensions.

Читать дальше