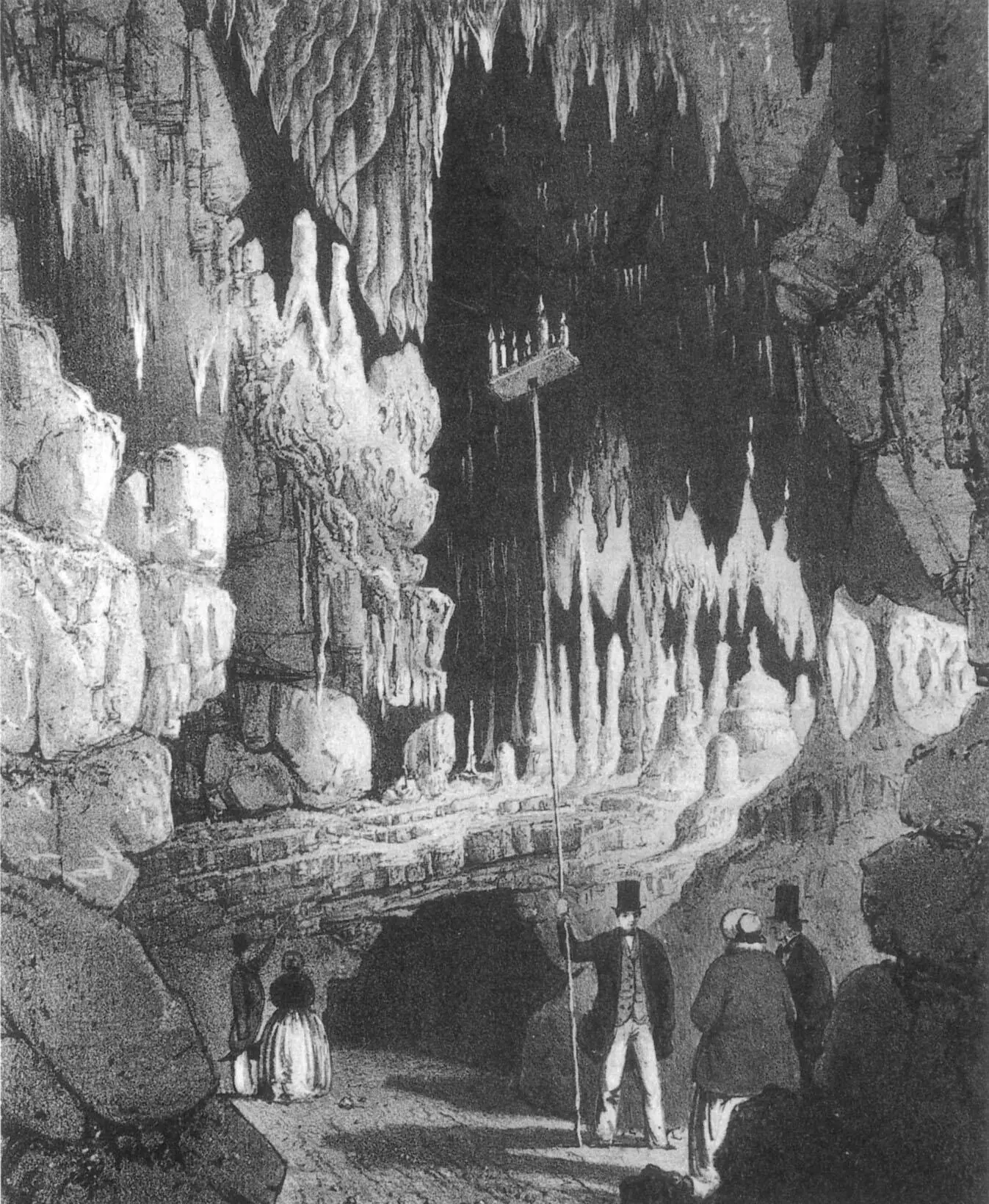

Fig. 1.5 Interior Chamber of Cox’s Stalactite Cavern, Cheddar, Somersetshire. Lithograph by Newman & Co. London; pub. S. Cox, Cheddar about 1850. (Courtesy of Trevor Shaw)

“I fastened a cord about me, and ordered them to let me down gently. But being down about two fathom I found the rocks to bear away, so that I could touch nothing to guide myself by, and the rope began to turn round very fast, whereupon I ordered the miners to let me down as quick as they could.”

He landed dizzy but safe 21 m below, on the floor of a cavern 35 m in diameter and nearly 37 m high within which he found large veins of lead ore. Surprisingly, Beaumont’s account failed to stimulate much curiosity about caves in scientific circles, and after a brief flurry of lead mining, the cave, known as Lamb Leer, was abandoned; its entrance shaft eventually collapsed and the sealed-off chamber was virtually forgotten for two centuries.

The rediscovery of Beaumont’s long-lost Lamb Leer cave took place in 1879, the same year that a young French law student, Edouard-Alfred Martel, made his first visit to the famous Adelsberg Cave in Slovenia (which was then part of Austria, but since World War II has reverted to its local name of Postojna Jama). Martel was completely enthralled, and in 1883 began to devote all his vacation time to cave explorations in the Causses of southwestern France. What set him apart from previous cave explorers, was his meticulous preparations and his systematic recording of all aspects of the caves he explored, combined with a tremendous physical ability and courage. His speciality was deep vertical pits, and in 1889 he successfully negotiated the 213 m vertical entrance shaft of the Rabanel pothole north-west of Marseilles – an outstanding feat given the equipment then available.

To calculate a pit’s depth, he would read the barometric pressure at the bottom and compare it with the surface pressure. He measured the horizontal dimensions of each newly-discovered chamber with a metal tape, drawing a sketch of the cave as he worked. Roof heights were calculated with an ingenious contraption: after attaching a silk thread to a small paper balloon, he would suspend an alcohol-soaked sponge beneath it, light the sponge, and measure off the length of thread carried aloft by the miniature hot-air balloon. Martel also habitually recorded subterranean air and water temperatures, finding variations with depth and season, and amassed whole volumes about cave geology, hydrology, meteorology and flora and fauna. But perhaps his greatest contribution to cave science was his research on how subterranean water circulates – a study prompted by his own bout with ptomaine poisoning, contracted from drinking spring water in 1891. After recovering from the illness, he traced the spring’s source using fluorescein dye introduced to nearby sink holes. Descending the appropriate pit, he found the putrefying carcass of a dead calf that had contaminated the spring with what he wryly termed “veal bouillon”. Further study allowed him to distinguish between “true springs”, fed by diffuse circulation of rainwater, cleaned and filtered by its passage through soil and rocks, and “false springs” fed by a rapid flow from sinkholes via cave passages too large to filter out impurities. Martel’s subsequent campaigning for stricter control of sources of drinking water eventually led to a dramatic reduction in deaths from typhoid and won him a gold medal from the French Government.

In 1895 Martel founded the French ‘Société de Spéléologie’, arguing that ‘ speleology ’, which had been previously considered a sport or a singular eccentricity, should be recognized as a fully-fledged science – “a subdivision of physical geography, like limnology for lakes and oceanography for seas.” A prolific author, he edited Spelunca , his Society’s bulletin, and wrote books about his own cave discoveries. In 1907 the French Academy of Sciences awarded him the grand prize for physical sciences, and in 1928 he was elected president of the Geographical Society of Paris. By the time he died in 1938, aged 78, the grand old man of speleology had personally probed nearly 1500 caves, hundreds of which had never been entered before; his technical innovations had become standard equipment for other cavers; and above all, his persistence and dedication had created a framework within which the seedling science of speleology could develop and blossom.

Meanwhile, the systematic documentation of caves had also started in Britain, with the formation of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club in 1892. Under the influence of S.W. Cuttriss, dubbed ‘the scientist’ for his assiduity in recording the group’s findings, its members drew up surveys of the caves they explored, and kept notes of temperatures, altitudes and geographical features.

The great exploration challenge of the day was the awesome Gaping Gill, a pothole high on the slopes of Ingleborough Hill which had been plumbed to a depth of 110 m, but had never been descended. The main obstacle to its exploration came from Fell Beck, an icy stream which cascades down the entrance, filling it with spray and extinguishing any flame which might light a caver’s descent, as well as half-drowning him. A local man, John Birkbeck, had made two heroic, but unsuccessful attempts to descend the pit in the 1840s, after digging a trench to divert the Fell Beck to another sink. His first try nearly proved fatal, when strands of his rope were severed on a rock ledge, but on his second attempt he reached a ledge at 58 m which now bears his name. Yorkshire Ramblers’ member Edward Calvert took up the challenge and had almost completed his own preparations for a descent on rope ladders in 1895, when Martel arrived on the scene, hot-foot from London where he had been invited to address an International Geographical Congress on cave-hunting methods.

As something of a celebrity, Martel was encouraged by the lord of Ingleborough Manor to have a crack at the great pothole and given the support needed to refurbish and extend Birkbeck’s trench. On August 1, before an eager crowd, Martel knotted together his lengths of ladder and lowered them into the darkness. As he climbed down the four metre-wide shaft he was rapidly enveloped by “half-suffocating whirls of air and water” which soaked his clothes and the field telephone which he relied upon to communicate instructions to the back-up team who controlled his safety line from the surface. The cascade redoubled 40 m down and he had to descend through a “frigid torrent gushing from a large fissure”. Pausing on Birkbeck’s ledge to untangle the huge heap of rope which had lodged there, he continued into the unknown depths below. Sixteen metres on, the walls of the shaft suddenly receded and Martel found himself swinging like a pendulum near the roof of an immense chamber nearly 160 m long by 30 m high. He alighted on the floor only 23 minutes after he began the descent, and characteristically at once set about measuring and sketching his discovery. For an hour and a quarter, the Frenchman revelled in the spectacle of the “Hall of the Winds”, Britain’s largest underground chamber from whose roof the waters of the Fell Beck tumbled “in a great nimbus of vapour and light”. There was a certain sense of nationalist triumph too: “The most pleasant feature was the thought that I had succeeded where the English had failed, and on their own ground.”

Fig. 1.6 Gaping Gill – the main chamber showing the waterfall falling 110 metres from the surface. A photograph taken in the 1930s by Eli Simpson. (Trevor Shaw collection)

Читать дальше

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)