In the context, the arrival of Clarke proved fortuitous: his glowing reports of Bonaparte’s ability and devotion to the Republic persuaded the Directors that it was best to retreat. On 6 December 1796, they abolished the role of commissioners altogether.

Meanwhile, Josephine had returned to Milan and a semblance of harmony was restored. She gave a ball on 10 December at which the couple presided in regal manner. Although he had a low opinion of Italians, considering them to be lazy and effeminate, morally defective and politically immature, Bonaparte went along with the wishes of the Milanese intellectual elites for an independent Italian republic. Pre-empting any hopes the Directory might still entertain of using Lombardy as a bargaining counter, on 27 December he announced the creation of the Cispadane Republic (covering the nearside of the river Po, Padus in Latin). It was given an armed force made up of Poles forcibly enlisted by the Austrians who had either deserted or been taken prisoner, under the command of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski.

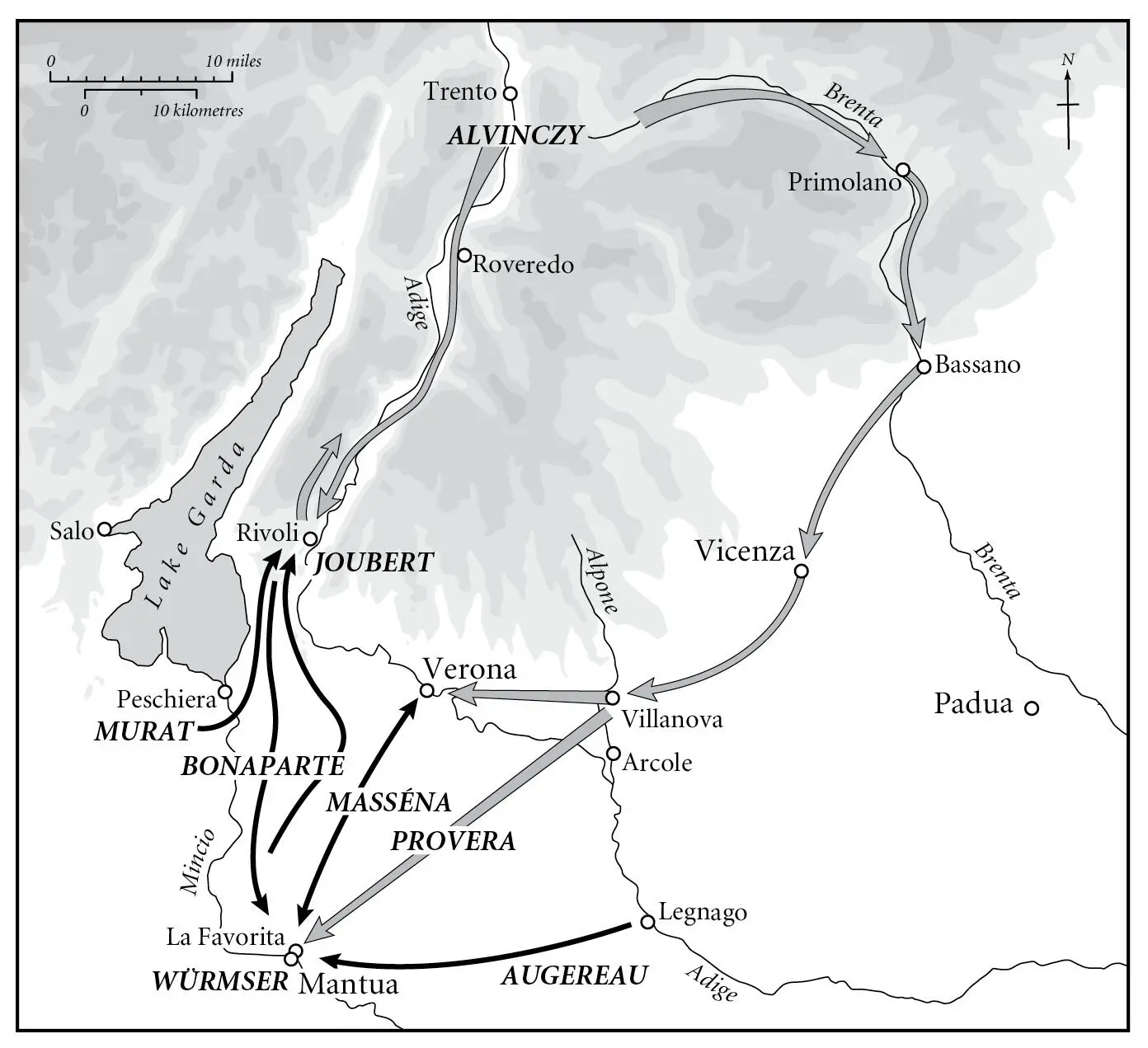

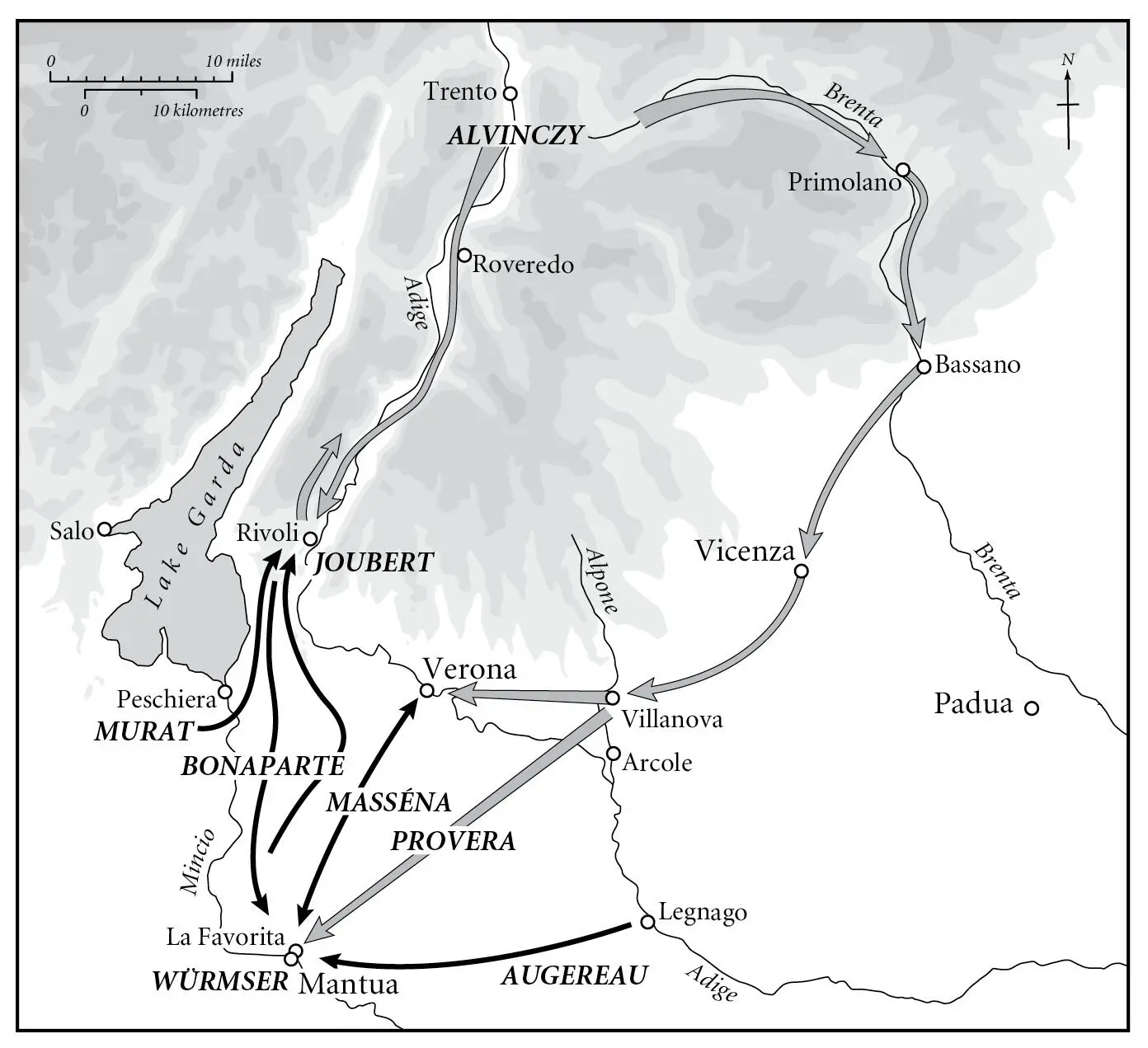

At the beginning of January 1797 the Austrians were on the move once more, Alvinczy marching down the valley of the Adige while two other corps swept down the valley of the Brenta to relieve Mantua. Leaving only a small force to parry these, Bonaparte collected all the troops he could muster and on the night of 13 January made a rapid march up to Rivoli, where Joubert was attempting to stem Alvinczy’s advance. He arrived at two o’clock in the morning and quickly took in the situation. Alvinczy had split his force into six columns, and Bonaparte set about them separately, defeating one after the other. By late afternoon Alvinczy was in full retreat. This was turned into a rout by the intervention of Murat on his flank, and the Austrians fled, leaving behind nearly 3,500 dead and wounded and 8,000 prisoners, representing 43 per cent of Alvinczy’s total effectives.

This obviated the need for pursuit, which was as well, since late that afternoon Bonaparte received news that one of the Austrian prongs to the south, under General Provera, had broken through and was close to Mantua. He ordered Masséna to gather up his exhausted troops and dashed south. On 16 January, while Colonel Victor contained a sortie from Mantua by Würmser, Bonaparte directed Augereau’s division against Provera at La Favorita outside the city, forcing him to surrender. It was an extraordinary result: in the space of less than four days he had depleted the Austrian forces by more than half. In the space of the week the French had taken 23,000 prisoners, sixty guns and twenty-four flags. With all hope of relief dissipated, Würmser would surrender Mantua and its garrison of 30,000 men, half of them too sick to walk, on 2 February, giving Bonaparte another twenty standards to send back to Paris. The victory had been achieved through extraordinary exertion – Masséna’s corps had fought at Verona on 13 January, at Rivoli the following day and outside Mantua two days later, covering ninety-odd kilometres in the process.

Bonaparte did not need to wait for the surrender of Mantua to know how complete his triumph was, and on 17 January he wrote to the Directors announcing that in the space of ‘three or four days’ he had destroyed his fifth imperial army. ‘I’ve beaten the enemy,’ he wrote to Josephine that evening. ‘I am dead tired. I beg you to leave immediately for Verona. I need you, because I think I am going to be very ill. A thousand kisses. I am in bed.’29

She did come, but there could be no question of a long rest. Austria would not admit defeat and was mobilising a new force. It was also negotiating with the Vatican and the kingdom of Naples, which had a sizeable army. The Directory had long before ordered Bonaparte to overthrow the papacy, which it regarded as the source of all obscurantism in the world and the avowed enemy of the French Republic. Bonaparte felt no animus against the Church and treated the clergy in the lands he occupied with respect, if only out of calculation. But he despised Pius VI, whom he regarded as a treacherous opportunist ready to stir against him every time the Austrians looked as though they might be winning. He was also short of cash, both for his army and to send back to France to placate his political masters, and there was no shortage of that to be found in Rome.

With 8,000 men, some of them Italian auxiliaries, he entered Bologna, where on 1 February he declared war on the Pope. He defeated a contingent of papal troops at Imola and took possession of Ancona. He had a cold and was depressed by the farcical nature of ‘this nasty little war’, as he wrote to Josephine on 10 February. Confronted by badly led mercenaries and displays of religious fanaticism, at Faenza he rounded up all the monks and priests of the place to lecture them about true Christian values.30

The Pope sent a delegation to negotiate, but the honey-voiced prelates who had been so successful with Garrau were no match for a bullying Bonaparte. By the Treaty of Tolentino, signed on 19 February, Pius ceded the former papal fiefs in France, Avignon and the Comtat Venaisin, the Legations of Bologna, Ferrara and Romagna, along with Ancona. He also agreed to close his ports to British ships, and undertook to pay 30 million francs and deliver a number of works of art and manuscripts.

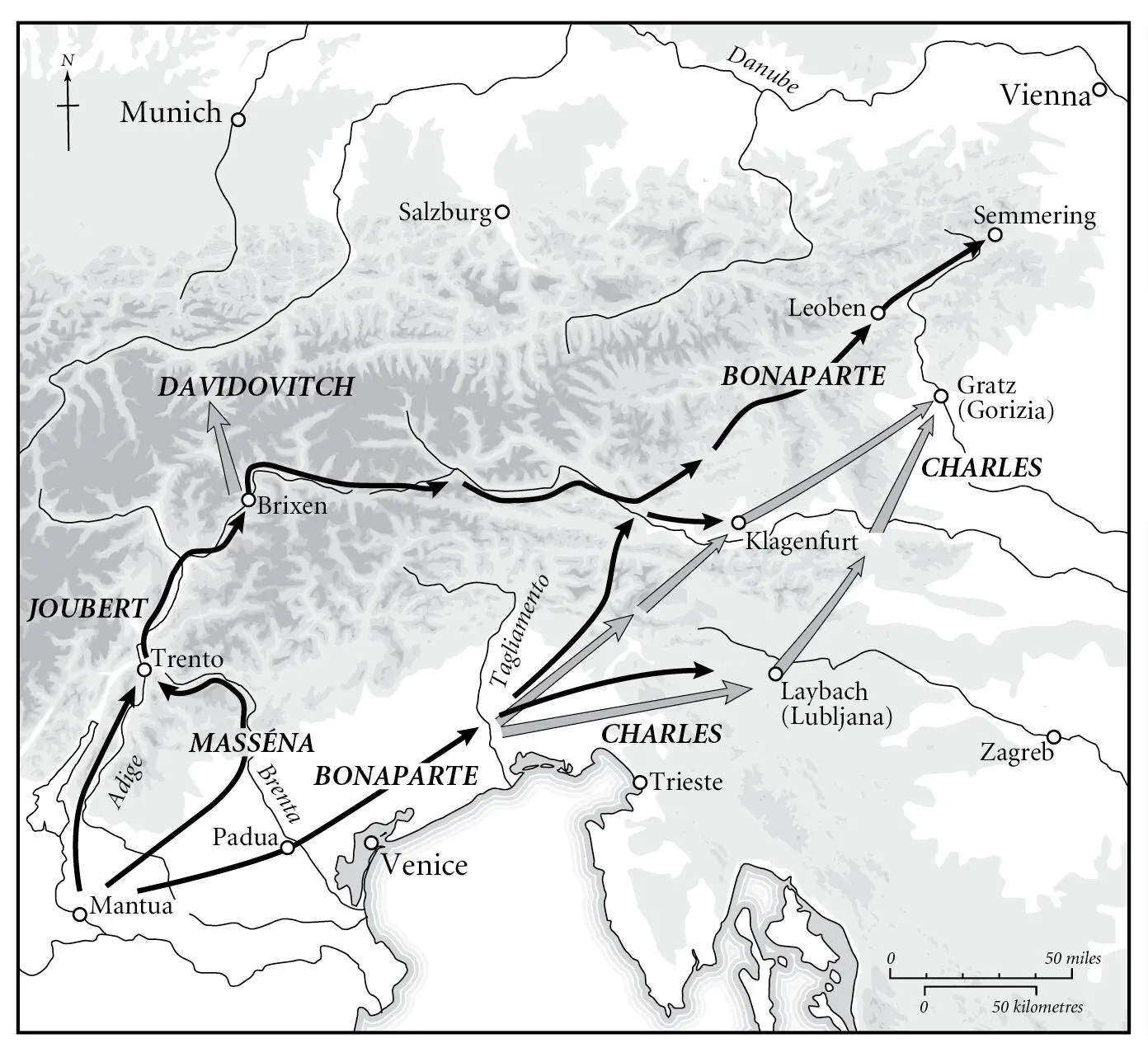

Five days later Bonaparte was back in Bologna with Josephine, who accompanied him to Mantua, where he prepared for the next campaign. The Directory had accepted that only he was capable of beating the Austrians decisively, and reversed its policy of treating the Italian theatre as a diversion. It transferred two strong divisions from the northern theatre, under generals Delmas and Bernadotte, reinforcing Bonaparte significantly: he could field 60,000 men while leaving 20,000 guarding his rear. This made him undertake what was under any circumstances a daring enterprise – a march on Vienna.

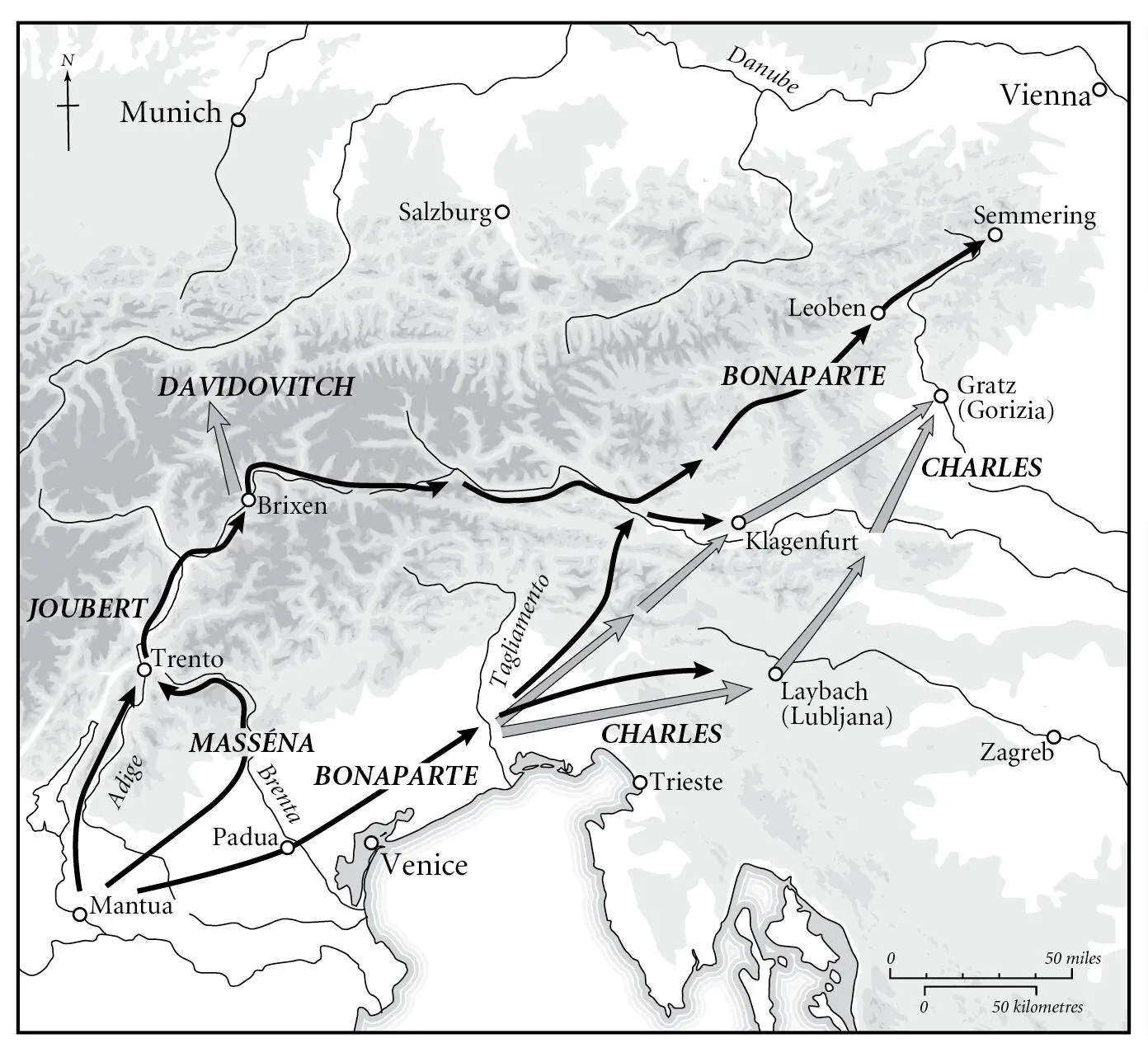

Three Austrian forces stood in his way, one under Davidovitch at Trento, another blocking the valley of the Brenta, and the main force concentrated along the river Tagliamento. They were under the overall command of Archduke Charles of Austria, a capable general two years younger than Bonaparte who had defeated the French in Germany. His presence was helping to restore the morale of the Austrian troops, and Bonaparte decided not to give him time. On 10 March he went into action, forcing Davidovitch up the valley of the Adige towards Brixen while Masséna advanced up the Brenta and Bonaparte took on the archduke himself on the Tagliamento. He breached his defences and forced him to fall back on Gratz (Gorizia) and Laybach (Lubljana). By then two of the passes were in French hands, and the archduke had to beat a hasty retreat if he were not to be cut off as Bonaparte reached Klagenfurt, on 30 March.

He was now poised to advance on Vienna, but if he did so, the Austrian armies in Germany could sweep into his rear. Behind him lay the whole of Italy guarded by a mere 20,000 men. Anti-French feeling simmered throughout the peninsula, with Naples, Venice, the papacy, Parma and Modena only waiting for a chance to strike. His army had advanced so far that it was running out of supplies, and the rocky region in which it now found itself would not sustain it for long. He therefore had to conclude peace urgently.

The one thing that would convince Austria to give in was a French advance across the Rhine by Moreau and Hoche, who had taken over from Pichegru, and Bonaparte sent request after request to the Directory urging it to order one. But he had learned to rely only on his own resources. On 31 March he offered Archduke Charles an armistice, but pressed on swiftly, reaching Leoben and taking the Semmering pass, less than a hundred kilometres from Vienna. There was panic in the Austrian capital, with people packing their valuables and leaving for places of safety. But with no support from Moreau and Hoche, Bonaparte could not afford to go any further. On 18 April preliminaries of peace were signed at Leoben.

Читать дальше