Buonaparte spent the first weeks of 1794 travelling up and down the coast inspecting the defences and issuing quantities of crisp instructions. These go into minute detail on the exact quantities of powder and shot required, which spare parts should be assembled, and even the manner in which horses should be harnessed for specific tasks.

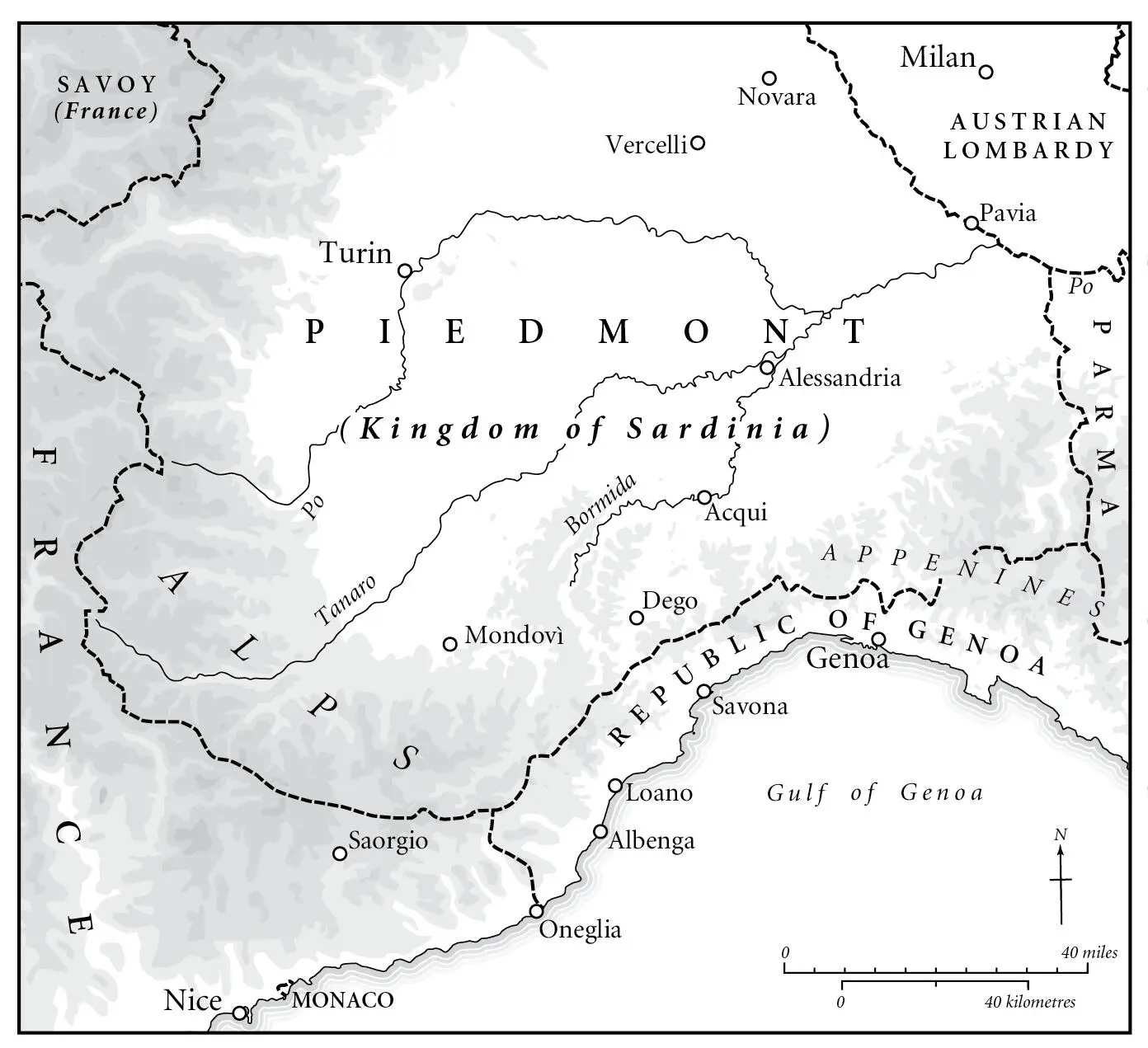

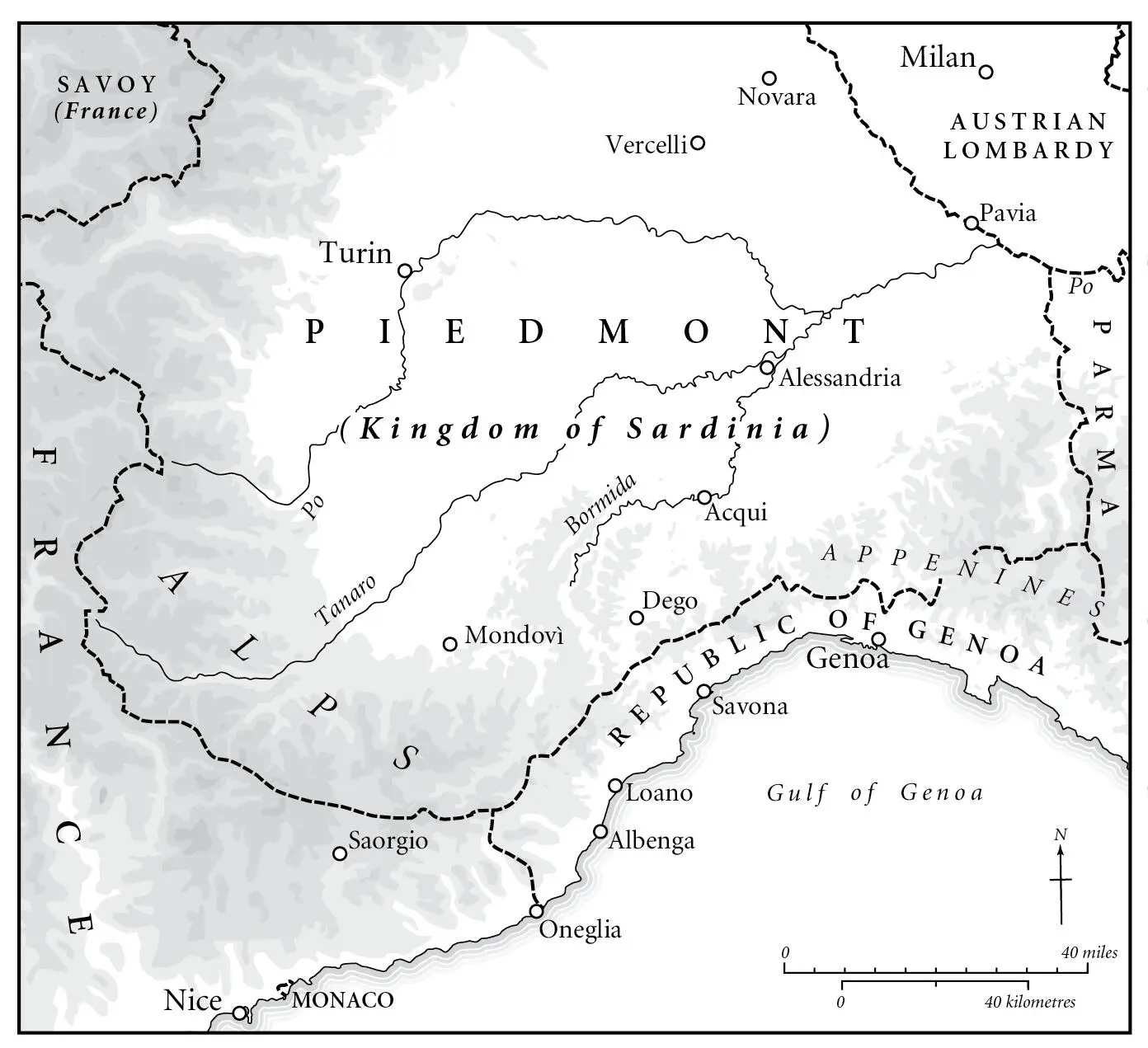

At the beginning of February he was appointed to command the artillery of the Army of Italy, operating against the forces of the King of Sardinia. They had invaded southern France in 1792 but were driven back, following which Savoy and Nice had been incorporated into the French Republic, but they still held the Alpine passes, from which they threatened to recover the lost provinces. The port of Oneglia, a Sardinian enclave in the territory of the neutral Republic of Genoa and the chief link between the king’s island and mainland provinces, was also considered a threat, since it resupplied British warships and harboured corsairs who preyed on French shipping.

Buonaparte’s new salary allowed him to install his family in the comfortable if modest Château-Sallé outside Antibes, not far from his headquarters in Nice. Joseph, whose job as commissary had awakened an interest in trade and speculation, was currently in Nice too, exploring business opportunities. Lucien was at Saint-Maximin, where as head of its Jacobin club he had changed the town’s name to ‘Marathon’, in homage as much to the ‘martyr of the Revolution’ Jean-Paul Marat, who had been assassinated in his bath by the royalist Charlotte Corday, as to the heroic ancient Greek defenders of their homeland. He had also changed his own name, to ‘Brutus’, and had married Christine Boyer, the sister of the keeper of the inn at which he lodged.1

The commander of the Army of Italy was General Pierre Dumerbion, a sixty-year-old professional. He was supervised by the political commissioners Saliceti, Augustin Robespierre and Ricord, who commissioned Buonaparte to prepare a campaign plan. As the Sardinian positions in the mountains were almost unassailable, he suggested ignoring them and striking at their bases: their left wing on the lower ground nearer the sea was vulnerable, and if the French could break through there, they would be able to sweep into the enemy rear. His plan was accepted, and operations began on 7 April, spearheaded by General André Masséna, who captured Oneglia two days later, and by the end of the month the French were in Saorgio, strategic gateway into Piedmont.

Buonaparte’s role consisted of ensuring the artillery was in position and adequately supplied. To assist him he had selected two old comrades from the regiment of La Fère, Nicolas-Marie Songis and Gassendi, his new companions Marmont and Muiron, and as aides-de-camp Junot and his own younger brother Louis. By 1 May he was back in Nice, drawing up further plans which would have taken the French into the plain of Mondovi, but the operations were halted by the war minister Lazare Carnot, who was against involving French forces any deeper in Italy. The Midi was still politically unstable, and there might be unrest if the army moved off. Carnot also needed all available troops to roll back the Spanish invasion.

Buonaparte composed a memorandum for the Committee of Public Safety giving a strategic overview of France’s military position. He argued that invading Spain would yield no tangible benefits, while invading Piedmont would result in the overthrow of a throne that would always be inimical to the French Republic. More important, it would make it possible to defeat Austria, which would only make peace if Vienna were threatened by a two-pronged attack, through Germany in the north and Italy in the south. Austria, he argued, was the cornerstone of the coalition against France, and if it were knocked out that would fall apart.2

Robespierre suggested that Buonaparte accompany him to Paris. The two men had grown close over the past four months, drawn together by the zeal with which they approached their respective tasks and by the shared conviction of the need for strong central authority. Under the dominant influence of Robespierre’s elder brother Maximilien, the Committee of Public Safety in Paris was exercising just such authority, through a reign of Terror which sent thousands to the guillotine. But Robespierre’s grip on power was weakening, and Augustin’s suggestion that Buonaparte come to Paris might have had something to do with that: he allegedly suggested placing him in command of the Paris National Guard.3

Buonaparte briefly considered the proposal, and according to Lucien discussed it with his brothers before deciding against it. To Ricord he admitted a reluctance to get involved in revolutionary politics, and his instinct was to stay at his post with the army. Whether the fact that he was also having an affair with Ricord’s wife Marguerite had any bearing on his decision is unclear.4

At the beginning of July he was sent by Saliceti to Genoa to assess the intentions of the city’s government, which was neutral but under pressure from the anti-French coalition, and to inspect its defences for future reference. He left on 11 July, accompanied by Junot, Marmont and Louis, as well as Ricord, but was back at Nice by the end of the month. Yet he was too busy to attend the wedding of his brother Joseph on 1 August.5

Joseph’s bride, Marie-Julie Clary, was twenty-two years old, not pretty, but pious, honest, generous, dutiful, family-minded, intelligent and rich. She came from a family of Marseille merchants with extensive interests in the ports of the eastern Mediterranean, and she brought him a considerable dowry. With this under his belt, Joseph’s bearing changed, and he now assumed a gravitas he felt appropriate as head of the family.6

Buonaparte was still at headquarters when, on 4 August, news reached him of the coup in Paris which had toppled Robespierre on 27 July – 9 Thermidor in the revolutionary calendar. He was deeply affected by the misfortune of his friend, who was guillotined along with his brother the following day. And he did not have to wait long to be arrested himself.7

As soon as he heard of the fall of Robespierre, Saliceti wrote to the Committee of Public Safety accusing Augustin Robespierre, Ricord and ‘their man’ Buonaparte of having sabotaged the operations of the Army of Italy and conspired against the Republic with the allies and with Genoa, whose authorities had bribed Buonaparte with ‘a million’ (the currency was not specified). He ordered the arrest of Buonaparte and the seizure of his papers prior to his being sent to Paris to answer charges of treason.8

It is not clear whether Buonaparte was actually put in gaol or merely under house arrest. Junot managed to pass a note to him offering to arrange his escape, but Buonaparte refused. ‘I recognise your friendship in your proposal, my dear Junot; and you well know that which I have vowed you and on which you know you may count,’ he wrote back. But he was confident his innocence would be recognised and urged Junot to do nothing, as this could only compromise him. Innocence was no guarantor of safety under revolutionary conditions, but Buonaparte was lucky. Saliceti’s accusation had been no more than a reflex of self-preservation, and as soon as he felt he was in the clear he sent another letter to Paris stating that examination of the general’s papers had yielded no evidence of treason, and, bearing in mind his usefulness for the Army of Italy, he and his colleagues had ordered his provisional release. Nobody apart from Junot seems to have taken the charges against Buonaparte seriously. His landlord Joseph Laurenti, with whose daughter Buonaparte was carrying on a flirtation, had stood bail, and as a result he spent most of the eleven days of his detention in his own lodgings.9

Читать дальше