Vin Packer

www.spice-books.co.uk

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

SIGN ME UP!

Or simply visit

signup.millsandboon.co.uk

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

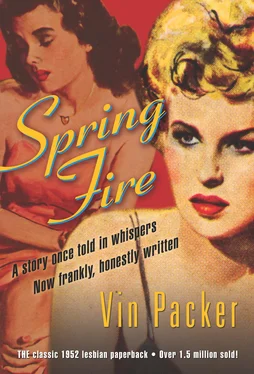

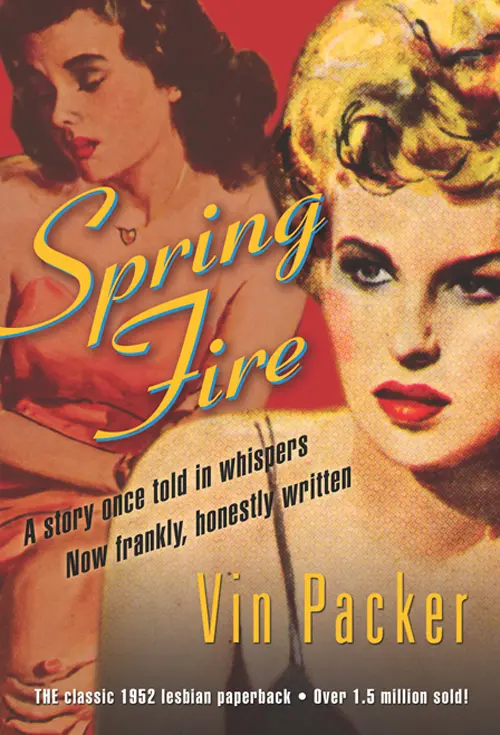

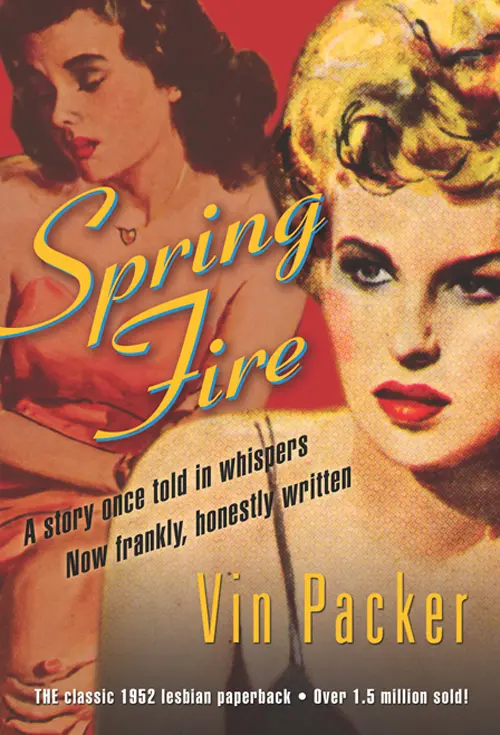

Cover

Title Page Spring Fire Vin Packer www.spice-books.co.uk

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Endpages

Copyright

INTRODUCTION by Vin Packer

I was having drinks in a little bar inside the Algonquin Hotel, with an editor named Dick Carroll, when he asked me, “What kind of story is a young girl like you burning to tell?” He was grinning at me, as though any answer to that question would be frivolous and lightweight. After all, I had gone to work for him straight out of college, only months before. I roomed with three sorority sisters. I was just finding my way around New York City.

I said, “I’d like to write about boarding school. I went because I had heard homosexuality ran rampant in places like that. I wanted to find out if my suspicions were right, that I was one of those. Sure enough, I was rewarded with first love.”

“A little love story with a twist, hmmm?”

“Yes, but not a happy ending. I didn’t think I was strong enough to go through all the secrecy and disapproval. Her mother found one of my letters to her and called my parents threatening to call the police if I ever contacted her daughter again.”

“What happened next?” Dick asked.

“My parents told me, and I told myself, that it was just a silly schoolgirl thing. All I needed to do was put myself in a male/female environment. So I chose the University of Missouri, co-ed, and with a fine journalism school, since I wanted to be a writer.”

“Were you cured?” Dick asked.

“I had a wonderful time. I pledged a sorority. I fell in love with a Hungarian who’d escaped the Holocaust. I began to write story after story. That was when I learned there wasn’t a cure. My Hungarian wasn’t enough, nor were my friends, and my stories were missing something, too. So that’s what I’d like to write about, if there were a way.”

Dick told me maybe there was a way.

He was the new editor of a line of paperback originals called Gold Medal Books, brought out by Fawcett Publications. The idea that good books could appear in paper without having to be in hardcover first was new. I was one of Dick’s secretaries, who didn’t know how to take shorthand, so I was assigned to read books thought to have potential, selected from the slush pile. A would-be writer, I very often finished reading a new manuscript thinking: I could do that .

“You might have a good story there,” Dick said, “but you’d have to do two things. The girls would have to be in college, not boarding school. And, you cannot make homosexuality attractive. No happy ending.”

“Well, my story didn’t have a happy ending, anyway.”

“But your main character can’t decide she’s not strong enough to live that life,” Dick said. “She has to reject it knowing that it’s wrong. You see, our books go through the mails. They have to pass inspection. If one book is considered censurable, the whole shipment is sent back to the publisher. If your book appears to proselytize for homosexuality, all the books sent with it to distributors are returned. You have to understand that. I don’t care about anybody’s sexual preference. But I do care about making this new line successful.”

“In other words, my heroine has to decide she’s really not queer.”

“That’s it. And the one she’s involved with is sick or crazy.”

He told me that if I wrote an outline and submitted it with one chapter, he would advance me $1000.

A month later, Sorority Girl was on the Gold Medal Schedule. Since they paid a penny a copy on print order, and usually printed 400,000 copies, I would receive $3000 more when I was finished.

After Dick read the final manuscript, he said we would have to change the title.

“It has no particular sales pull,” he said.

“I don’t want it to have an unhappy title like The Well of Loneliness , ” I said.

“Neither do I,” said Dick. “I want to call it Spring Fire.”

“What? What does that even mean?”

“It means there’s a big seller by James Michener called The Fires of Spring , and we might pick up a few readers who confuse the titles.”

I just stared back at him in disbelief.

“Look,” he said, “I’m taking a big chance here because this is the story you told me you wanted to write. Fawcett Publications is taking a chance, too. Do you really think there’s much of an audience out there for this? It’s set in a sorority, for Pete’s sake! We have to jazz up the title and wrap it in a sexy cover. We have to! This is a business.”

So it was that the book was called Spring Fire , and at the end one young woman goes mad, while the other realizes she had never really loved her in the first place. While that may have satisfied the post office inspectors, the homosexual audience would not have believed that for a minute. But they also wouldn’t care that much, because more important was the fact there was a new book about us. Suddenly, we were on the newsstands and in the magazine stores, right up front on the racks.

Lesbians and homosexuals, in those days, had no sense of entitlement. The majority of us were closeted. A lot of us went to big cities so we could find others, mostly in bars catering to us. I was still dating men. My sorority sisters knew nothing about my homosexual love affair in boarding school. They had no idea that more and more when I went on dates, I was asking my “boyfriends” to find bars where lesbians went, claiming that I wanted to do an article about such women. Although the word gay was becoming popular among us, it had not yet been mainstreamed. There were no magazines or newspapers about us, no clubs for us to belong to. Books written about us were very few with small print orders, and not reviewed in major publications. We were never mentioned in radio dramas or soap operas and needless to say as television got started, we were not in the scripts. The church and synagogues called us sinners, as they still do, and the law called us criminals. We had no legitimacy.

This is not to say the “twilight path” was filled with broken glass.

We had good times despite our oppressors, the rules against us, and our invisibility. But it would be many years before enough of us gained the self-respect that made us fight against the labels “abnormal” and “perverse,” and begin to realize our numbers, our strength, and our potential politically.

In 1952 when Spring Fire was published it sold 1,463,917 copies in its first printing, more than The Postman Always Rings Twice by James Cain and more than My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier sold in that same year.

Читать дальше