Over the sound of burned crusts against my teeth I heard a knock on the door, and Prosper Lost peeked in at us. He was the Lost Arms’ proprietor, a word which here means he stood around the lobby with a small smile and called it running the place. I called it a little creepy, although not to his face. “Lemony Snicket,” he said.

“You’re not Lemony Snicket,” Theodora said to him.

“There’s someone downstairs to see you,” Lost explained to me.

Theodora frowned at the proprietor. “Whoever’s waiting downstairs isn’t Lemony Snicket either,” she said. “Lemony Snicket is right here with crumbs on his shirt.”

“Someone is here to see Lemony Snicket,” Prosper Lost said, as clearly as he could.

“Thank you,” I told the proprietor, and excused myself.

“Whatever you’re doing,” Theodora called after me, “be quick about it. You have a very busy day, Snicket. You have to buy some napkins.”

My mouth wasn’t full, but I pretended it was so I didn’t have to answer as Prosper Lost led me down the stairs. “Who is it who wants to see me?” I asked him.

“A minor,” Lost replied.

“Do you mean a child, or someone who works in a mine?”

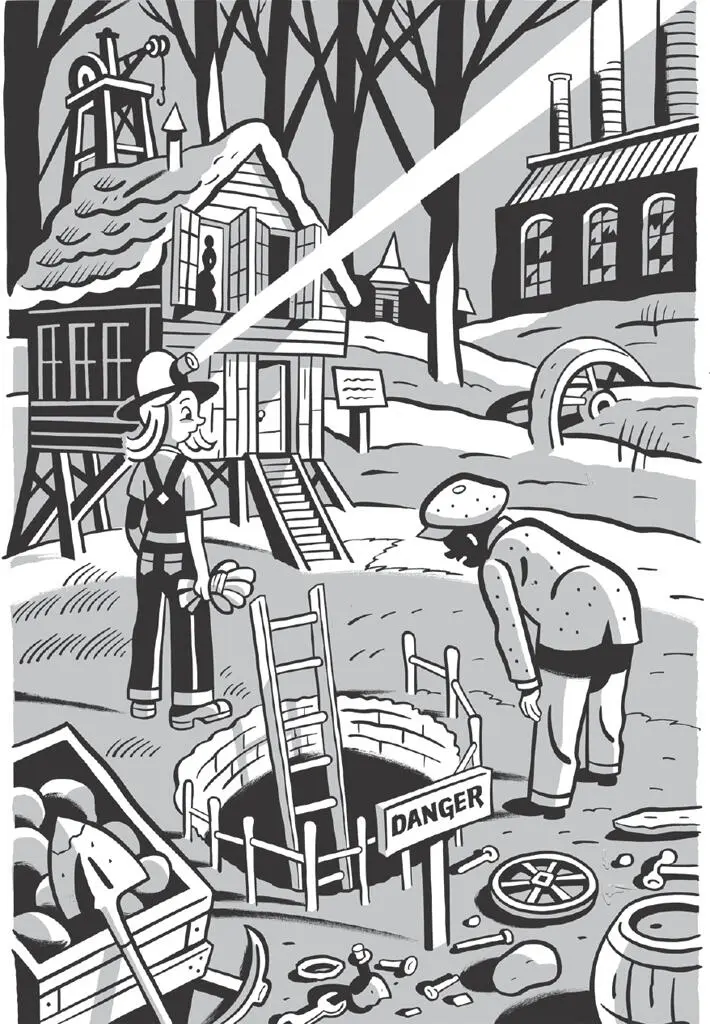

“Both,” Lost said, and sure enough, in the lobby was a girl about my age wearing a helmet with a light attached to it, the kind people wear when digging underground. The hat looked a little big on her head, and she took off some oversized work gloves so she could shake my hand.

“I’m Marguerite Gracq,” she said. “I spell it in the French way.”

“I’m Lemony Snicket,” I said. “I think my name is spelled the same in any language.”

“Around town they say you’re something of a detective.”

“Around town they’re wrong. I’m something else.”

“Well, I need some help.”

“What kind of help?”

“Pictures are falling down in my living room.”

“Sounds like you need a handyman.”

Marguerite shook her head. “They’re falling too neatly.”

“Maybe it’s just because I’ve had a lousy breakfast,” I told her, “but I’m not following you.”

“Follow me to my home,” Marguerite said, “and I’ll explain everything and poach you an egg, besides. I put a little vinegar in the poaching water, so my eggs turn out nice and fluffy.”

A fluffy poached egg is a good breakfast, and a good breakfast is better than a bad one, like a good book is better than having your toe chopped off. We walked out of the Lost Arms together and down the quiet street. Most of the streets in Stain’d-by-the-Sea were quiet. The town was emptying out.

“I know that most businesses in town have been failing,” I told Marguerite, with a nod at a boarded-up shop. “How’s mining going?”

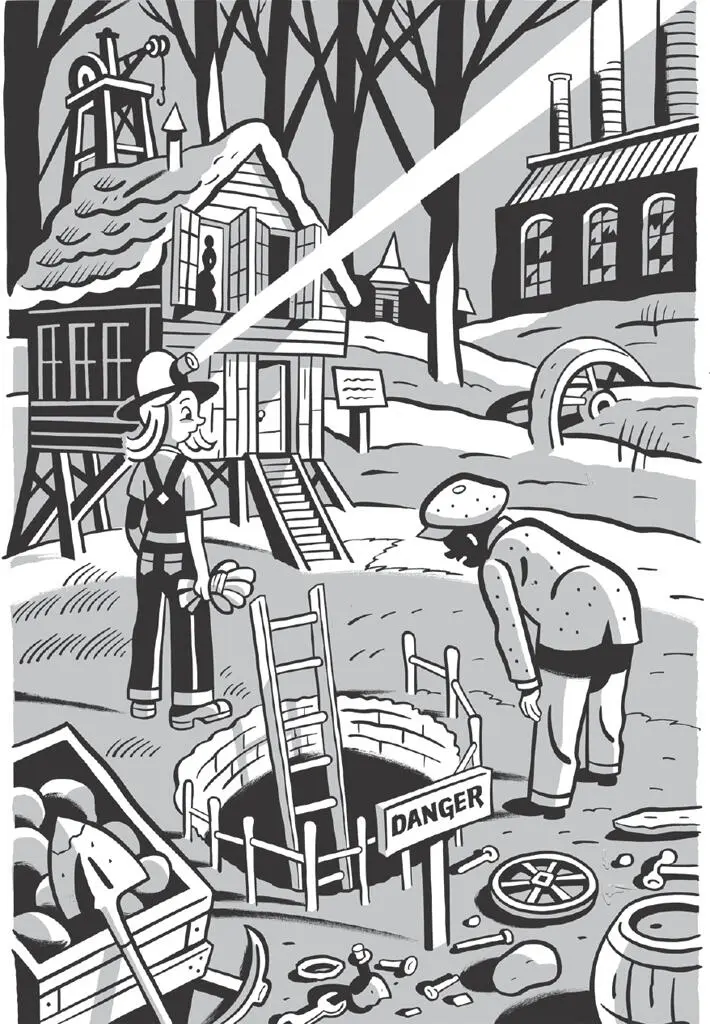

“There’s just one small mine in Stain’d-by-the-Sea,” she said, “and it’s in my front yard. My father says we’ve gotten all the gold we’re going to get from it. He’s out of town for a few weeks finding us a better place to live. I’m staying here to close up the mine and make sure nothing happens to the gold.”

“He left you here all alone?”

Marguerite frowned and shook her head. “He hired a woman named Dagmar to watch over me. She doesn’t do much but sit and listen to the radio. I don’t like her.”

“What does she listen to?”

“Polkas.”

“No wonder you don’t like her.”

Marguerite smiled. “That’s not the only reason,” she said. “Dagmar doesn’t seem trustworthy. The paintings didn’t start falling until she arrived, and nobody else has been around. I keep thinking she’s after something, but nothing has been stolen.”

“Most untrustworthy people hanging around a gold mine are after the gold.”

“My father has been very careful about his stash,” she said. “When we bring gold up from the mine, he immediately takes it all to his workshop to melt it down. Then he hides it someplace in that room. Even I don’t know exactly where, and I have the only workshop key. My father gave it to me when he left town, and I keep it with me always.”

Marguerite reached into her overalls and drew out a skinny key on a thick cord around her neck.

“Have you ever let Dagmar use the key?” I asked. “She could have had a copy made.”

Marguerite shook her head. “I’m the only one who’s been in the workshop since my father left, and I can see that nothing has been touched. The problem’s not with the gold, Snicket. It’s with the pictures in my living room.”

We’d arrived at a small wooden house with a roof covered in moss, narrow windows wide open, and a large hole in the front yard with the top of a ladder jutting out from it. Various tools were scattered around the browning lawn. From the windows I could hear a particularly peppy polka. All polka music is peppy. There’s nothing wrong with feeling peppy, but a polka insists that everyone else has to be peppy too, even if they don’t feel like it.

Marguerite kicked off her boots and led me into a friendly-looking place. There was a large wooden staircase with piles of books here and there, and a carpet decorated with images of mythical beasts and smudges of dirt. Leafy plants hung in the windows, shedding leaves wherever I looked.

“I’m back, Dagmar,” Marguerite called upstairs. “I have a friend with me! I’m going to make him a poached egg!”

“Do whatever you want,” replied a cranky voice, over the sound of the polka. The music’s peppiness had clearly not spread to Dagmar.

“The kitchen’s right over here,” Marguerite said, “but if you don’t mind, I’d like to show you the living room first.”

“Of course,” I said, and she led me through an archway into a room as pleasant and rumpled as the rest of the house. The wooden floor was painted black, with the paint peeling off here and there, and the sofas and chairs were all bright yellow except where they were patched up with squares of other bright fabrics. There was a large reading lamp, made from another miner’s helmet, and on the walls were portraits of pale, thoughtful-looking people, with one portrait leaning against the wall underneath a blank space on the wall where it clearly belonged. One portrait, depicting a man with a bow tie and an elegant cane, had a large rip right across the middle, and Marguerite looked at it sadly. “Henry Parland was the first one to fall,” she said, “just a few minutes after Dagmar arrived. Luckily, it’s the only one that’s been damaged. Since then, it seems that one falls whenever I’m down in the mine. Paavo Cajander, Katri Vala, Eino Leino, Otto Manninen, and this morning Larin Paraske, who had already fallen, was found right as you see her, leaning on the wall like all the others.”

“Your father certainly likes Finnish poets,” I said.

“These portraits belonged to my mother,” Marguerite said. “They were precious to her, but they’re not particularly valuable.”

“And they haven’t particularly been taken,” I said.

“Nothing has,” Marguerite said, looking around the room. “I admit I’m suspicious of Dagmar, but I can’t say she’s committed any kind of crime. The paintings just keep falling and then we hang them back up.”

“You say they fall when you’re in the mine,” I said, glancing out the window at the hole in the yard, “but surely you can’t hear them fall from down there.”

“Dagmar tells me they’ve fallen,” Marguerite said, “or I notice myself when I come in for a snack.”

“And who puts them back up?”

“I do,” Marguerite said, with a note of pride in her voice. “I fetch a hammer and a nail from the workshop and do the job myself. And I do it right, Snicket. Don’t think it’s my fault they keep falling.”

Читать дальше