‘Come on,’ said Salter. ‘We need to look for the boat and our stuff before the tide takes it back.’

Moss looked at the black river doubtfully. But she knew he was right. If there was a chance they could find it, they had to try. A broken boat and two wet blankets were better than nothing at all.

They scrambled back to the water’s edge and worked their way up the shoreline, prodding and scouring. But all they found were bits of old crate, bricks and bones, coughed up by the tide.

‘This is hopeless.’ Moss turned from the river and stared up the shore. Not far off, slumped like a tired army in the mud, were the fishermen’s tumbledown huts.

Salter was shaking his head. ‘Where is it?’ he muttered.

‘Let’s face it, the boat’s gone,’ said Moss. ‘We need to find somewhere to sleep. Salter ?’

‘Here,’ he said. ‘It was here .’ He was dashing to and fro like a mouse that had lost its hole. ‘It was here . I swear on me old nan’s teeth.’

Then he stopped. Sniffed the air. And looked down. Now he was on his knees, scrabbling in the shingle.

‘Salter, what are you doing?’

He pulled a piece of charred wood from the stones. ‘The smoker . . .’ He took a few steps forward and blinked with disbelief, turning in a slow circle and looking at the ground. He was standing on what could only be described as a pile of broken sticks.

And then she understood.

‘Oh, Salter, I’m sorry –’

‘Me old shack. It’s gone.’

Moss stared helplessly at where Salter’s hut had been. Never much to look at from the outside, inside the shack had been snug as two cats. Now it was smashed to tinder. A heap of wood, barely enough for an hour’s blaze.

‘Salter,’ she said gently, ‘it can’t be helped. All those children on the riverbank, hungry and frozen. When they realised you weren’t coming back, they’d have taken what they could. Come on. You’d have done the same.’

‘Maybe I would,’ said Salter gruffly. ‘But you ain’t never built somethin with yer bare hands, only to find it pulled to pieces like a chicken from its bones . . . Wait a minute.’ He patted his pockets. ‘Cussin collops!’ He kicked at the ground, sending a spray of shingle into the river. ‘All me coins must’ve fallen out.’

No money, no blankets and no boat. At least there were fires on the shore. There was a chance they wouldn’t freeze to death. They traipsed back to the bonfire and sat huddled together, backs to the heat, as close as they could get without setting themselves alight. And Moss must have forgotten the cold, because at some point she felt her head fall gently against Salter’s shoulder.

In the distance, cries and cheers mixed with the hush of the waves.

‘You asleep, Leatherboots?’ murmured Salter.

She was too tired to reply. But as sleep came, she felt the lightest touch of something soft on her forehead.

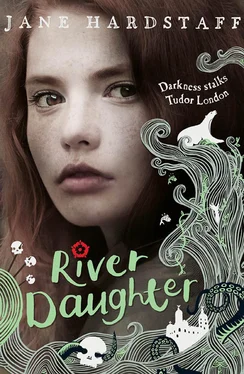

CHAPTER SIX 6 Cat’s Head 7 Eel-Eye Jack 8 The Great White Bear 9 On the Roof of The Crow 10 Little Elizabeth 11 Whipmaster 12 Hiding 13 The Pit 14 Catching Salmon 15 Salter’s Way 16 Jenny Wren 17 Slider 18 The River Inside 19 Friendship Broken 20 Bladder Street 21 Princess Redhead 22 An End to All This 23 Bear Fight 24 The Slider Rises 25 Boat of Leaves A note from the author Acknowledgements Also by Jane Hardstaff

Cat’s Head 6 Cat’s Head 7 Eel-Eye Jack 8 The Great White Bear 9 On the Roof of The Crow 10 Little Elizabeth 11 Whipmaster 12 Hiding 13 The Pit 14 Catching Salmon 15 Salter’s Way 16 Jenny Wren 17 Slider 18 The River Inside 19 Friendship Broken 20 Bladder Street 21 Princess Redhead 22 An End to All This 23 Bear Fight 24 The Slider Rises 25 Boat of Leaves A note from the author Acknowledgements Also by Jane Hardstaff

A howling river wind woke Moss early next morning. She lifted her head and sat up. Salter was still asleep, propped against an empty beer barrel. She guessed he’d dragged it over to the fire to shield them from the wind. She stood up and shook out her dress. It was smoky and specked with ash, but the wool was bone-dry next to her skin. Silently she thanked Pa. Without a blanket or a groat to her name, this dress was all she’d got.

‘Arrggh.’ Salter groaned himself awake. He stretched and his neck cricked. ‘Sweet Harry’s achin bones! Feels like someone chopped me head off and put it back the wrong way.’

Moss didn’t hear him. She was already down by the water’s edge, walking along the shore. The strangeness of their river journey was fresh in her mind – snatched by a freak current and dumped right in front of the Tower.

‘Hey! Leatherboots! Wait for me!’

Salter caught her up. ‘Where are you goin?’

‘Back to where we pitched up last night.’

‘Won’t do no good. Tide’ll have taken the boat. Won’t be nothin to find now.’

‘I know. I just –’ She broke off. What could she say? She wasn’t going to tell him about the Riverwitch.

But Salter was distracted by something else. The grey river raked the shingle, leaving a sticky sludge in its wake.

‘Steer clear of that mud, Leatherboots,’ said Salter. ‘You never know how deep this stuff is. Maybe it’s just an inch or two, or maybe it’s sinkin mud.’

‘Sinking mud?’

‘Deep as a pit, thick as porridge – mud that’ll trap you an’ pull at yer boots an’ the more you struggle, the more stuck you get. Till you ain’t got the strength to even call out fer help. And when it knows you ain’t goin nowhere, that mud will suck you down. Cold an’ thick an’ pressin the life from yer lungs. An’ there ain’t a thing you can do but watch yerself get swallowed slow.’

Moss stopped walking. ‘That’s what it felt like. That day the fish jumped out and I got stuck.’

Salter nodded. ‘It’s evil stuff an’ no mistake, an’ you don’t go near it if you can help it.’

They were almost at Tower Wharf. A putrid smell crept past Moss’s nostrils.

‘Holy dogbits!’ Salter’s nose caught the wind. ‘That’s disgustin! I think I’m gonna gip.’

The closer they got to the Tower, the stronger the smell, until Moss’s eyes were watering.

‘Hold it, Leatherboots. What is that ?’

Salter was pointing at a messy object, half buried in the mud not five feet from where they walked.

‘Wouldn’t touch it if I was –’

Too late. Moss was crouching by the muddy object, trying not to retch on the foulness that clawed its way down her throat.

It was a ball of matted fur, caked with river mud and what looked like old blood. Moss grabbed a stick and poked at it, rolling it over slowly. The matted fur was odd-looking. Speckled with a strange pattern, though it wasn’t easy to see through all the mud. The ball tipped on its side.

‘Oh!’

Moss jumped back.

Two startled eyes stared up at her – huge and black-ringed, faded by death. A lolling tongue poked through four enormous fangs. It was the head of some poor dead animal. Washed up by the tide.

Salter was beside her now. He whistled. ‘ That is one big cat. What’s it been feedin on? All the other cats in town?’

‘That’s no cat,’ said Moss.

‘Got cat ears,’ said Salter. ‘Got cat eyes. And I reckon them straw things plastered to its fur are whiskers.’

‘Look at its teeth,’ said Moss. ‘When did you last see a cat with fangs the size of parsnips?’

‘Well, what is it then?’

‘I don’t know.’

Читать дальше