First published in Great Britain in 1908 by Methuen & Co Ltd

Reissued in 2000 by Egmont Books

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

This edition published 2021 by Egmont Books

Text copyright © The University Chest, Oxford, under the Beme Convention

Line illustrations copyright © The Shepard Trust

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

Ebook ISBN 978 0 7555 0079 6

www.egmontbooks.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

or stored in a database or retrieval system, without

the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont Books is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

1 I The River Bank

2 II The Open Road

3 III The Wild Wood

4 IV Mr Badger

5 V Dulce Domum

6 VI Mr Toad

7 VII The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

8 VIII Toad’s Adventures

9 IX Wayfarers All

10 X The Further Adventures of Toad

11 XI ‘Like Summer Tempests Came His Tears’

12 XII The Return of Ulysses

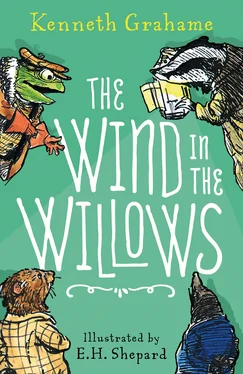

13 Back series promotional page

14 About the Author

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

I The River Bank

II The Open Road

III The Wild Wood

IV Mr Badger

V Dulce Domum

VI Mr Toad

VII The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

VIII Toad’s Adventures

IX Wayfarers All

X The Further Adventures of Toad

XI ‘Like Summer Tempests Came His Tears’

XII The Return of Ulysses

Back series promotional page

About the Author

I

The River Bank

The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash; till he had dust in his throat and eyes, and splashes of whitewash all over his black fur, and an aching back and weary arms. Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing. It was small wonder, then, that he suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said ‘Bother!’ and ‘O blow!’ and also ‘Hang spring-cleaning!’ and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat. Something up above was calling him imperiously, and he made for the steep little tunnel which answered in his case to the gravelled carriage-drive owned by animals whose residences are nearer to the sun and air. So1he scraped and scratched and scrabbled and scrooged, and then he scrooged again and scrabbled and scratched and scraped, working busily with his little paws and muttering to himself, ‘Up we go! Up we go!’ till at last, pop! his snout came out into the sunlight, and he found himself rolling in the warm grass of a great meadow.

‘This is fine!’ he said to himself. ‘This is better than whitewashing!’ The sunshine struck hot on his fur, soft breezes caressed his heated brow, and after the seclusion of the cellarage he had lived in so long the carol of happy birds fell on his dulled hearing almost like a shout. Jumping off all his four legs at once, in the joy of living and the delight of spring without its cleaning, he pursued his way across the meadow till he reached the hedge on the further side.

‘Hold up!’ said an elderly rabbit at the gap. ‘Sixpence for the privilege of passing by the private road!’ He was bowled over in an instant by the impatient and contemptuous Mole, who trotted along the side of the hedge chaffing the other rabbits as they peeped hurriedly from their holes to see what the row was about. ‘Onion- sauce! Onion-sauce!’ he remarked jeeringly, and was gone before they could think of a thoroughly satisfactory reply. Then they all started grumbling at each other. ‘How stupid you are! Why didn’t you tell him –’ ‘Well, why didn’t you say –’ ‘You might have reminded him –’ and so on, in the usual way; but of course, it was then much too late, as is always the case.

It all seemed too good to be true. Hither and thither through the meadows he rambled busily, along the hedgerows, across the copses, finding everywhere birds building, flowers budding, leaves thrusting – everything happy, and progressive, and occupied. And instead of having an uneasy conscience pricking him and whispering ‘Whitewash!’ he somehow could only feel how jolly it was to be the only idle dog among all these busy citizens. After all, the best part of a holiday is perhaps not so much to be resting yourself, as to see all the other fellows busy working.

He thought his happiness was complete when, as he meandered aimlessly along, suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before – this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shake and a-shiver – glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble. The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man, who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

As he sat on the grass and looked across the river, a dark hole in the bank opposite, just above the water’s edge, caught his eye, and dreamily he fell to considering what a nice snug dwelling-place it would make for an animal with a few wants and fond of a bijou riverside residence, above flood-level and remote from noise and dust. As he gazed, something bright and small seemed to twinkle down in the heart of it, vanished, then twinkled once more like a tiny star. But it could hardly be a star in such an unlikely situation; and it was too glittering and small for a glow-worm. Then, as he looked, it winked at him, and so declared itself to be an eye; and a small face began gradually to grow up round it, like a frame round a picture.

A brown little face, with whiskers.

A grave round face, with the same twinkle in its eye that had first attracted his notice.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)