In highly staged environments, meaning appears to emanate from the atmosphere itself. Atmospherics welds feeling and affect to the museum narrative. This can be understood as a variation of the “reality effect”: in literature, the way in which an accumulation of apparently insignificant details (details that don’t appear to be “signs” within the larger text) combine to produce a strong sense of realism (Barthes 1986). Hilde Hein sees immersive exhibitions as potentially creating “a public reality that passes for knowledge” (2000, 80). But this assumes that all exhibitions must be first and foremost factual representations. Yet, reality effects are part of the pleasures of fiction (which is never entirely invention), and in exhibition contexts they arguably help to construct temporary and playful worlds apart, rather than insidious substitutes for fact.

Reinventing exhibition space

Biehl-Missal and vom Lehm look at the development of atmospherics as a retail marketing tool in the context of the “experience economy” ( Chapter 11). They suggest that the production of staged atmospheres is about the production of value. In a time of corporate sponsorship and private–public partnerships, highprofile and often spectacular museums have become integral parts of new planned urban environments, alongside shopping centers, travel hubs, and other “cultural assets.” In his chapter, museum designer Peter Higgins lists some of the elements of increasingly vigorous attempts to market museums as destinations alongside other attractions and family days out: “including high-quality food and beverage, sophisticated retail, profitable temporary exhibitions, and corporate out-of-hours events” ( Chapter 14).

The global spread of neoliberal economics and ideology is particularly evident in the contemporary art world; as Mark Rectanus points out, art museums are entangled with private agencies, large-scale commercial events, and global art markets. Rectanus gives the example of corporate museums such as the BMW complex in Munich, and the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, South Korea, which combine educational, consumption, and entertainment facilities to reshape, not just the museum, but the urban environment ( Chapter 23). In the late 1980s the majority of commercial art galleries in London were to be found in Cork Street, Piccadilly, and had relatively small exhibition spaces. During the 1990s wealthy collectors and art patrons started to develop their own large exhibition spaces that could compete with museums (such as the Saatchi Gallery in St. John’s Wood). Today, London is full of museum-standard, huge white cube spaces which are privately owned and which sell contemporary art rather than collect it, such as the Gagosian, the Lisson Gallery, and Hauser & Wirth’s large Savile Row galleries. These private museums reconfigure social space more widely: in summer 2014 Hauser & Wirth opened another large-scale institution on a rural farm in the southwest of England with five galleries covering 2483 square meters, which will turn the small town in which it is situated into a key destination for contemporary art tourism (Shalam 2014). 6

Designing retail environments and designing museums involve different constraints and priorities: in the United Kingdom, Peter Higgins finds that National Lottery funding makes it difficult to adopt a holistic, integrated approach to the architecture and the interior, which is often “retro-fitted” into a spectacular but perhaps impractical building ( Chapter 14). In the case of the contemporary art museum, the competition for iconic buildings has been understood as the “visual expression” of an increased privatization in which “a collection, a history, a position or a mission” are demoted in favor of “cool” and “photogenic” environments (Bishop 2013, 11–12). Concerns about illusionistic environments and manipulative atmosphere implicitly suggest that there might be such a thing as a neutral exhibition space. Yet, even the white cube art gallery is a designed space, intended to facilitate particular understandings of the autonomy of modern or contemporary art.

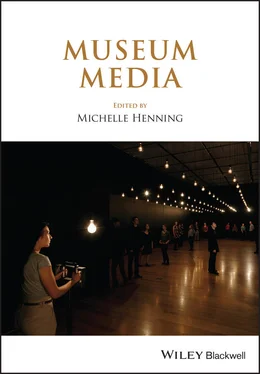

Exhibitions choreograph visitors; they produce a certain kind of social space. Herbert Bayer, quoted earlier, suggested that exhibitions were and are exciting to design because they could involve so many different media and materials in the production of new kinds of experience. Higgins, whose company, Land Design Studio, has designed many major museums and exhibitions, calls his chapter (14) “Total Media” as an appeal for a more collaborative, holistic approach to museum-making, but also in recognition of the complex, multisensory, multimedia aspects of exhibition design involving the use of light, sound, and the “tactile and olfactory” alongside audiovisual and graphic elements.

Discussing the practices of the Stapferhaus in Lenzburg, Switzerland, Beat Hächler writes that space can be understood not as a container but as an arrangement of relationships, as a means of engineering certain performative possibilities. Indeed, since the 1920s, artists and designers have conceived of the exhibition space as an environment that changes as visitors move around it. It was a means of creating new experiences, new ways of seeing and exploring space, that corresponded with artistic practices aimed at transforming perception. Some of these exhibition experiments can be viewed today. For example, at the Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz in Łódz in Poland, Wladysław Strzeminski’s Neoplastic Room has been restored. The gallery, which originally opened in June 1948, is both a container for various works of art by Strzeminski and his contemporaries, and an immersive abstract artwork itself. The paintings and sculptural constructions within it are not simply the subject of the exhibition but are part of the same field of practice: like many avant-garde artists, Strzeminski worked in design and architecture as well as painting (Szczerski 2012, 237). 7

The Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven in the Netherlands has made a point of collecting, or reconstructing, historically important exhibition spaces and multimedia installations such as Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Workers’ Reading Room of 1925; El Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet, originally commissioned in 1927 for the Landesmuseum in Hanover, Germany, by Alexander Dorner and destroyed in 1936; and Lászlo Moholy Nagy’s Room of Our Time (1930), which was never constructed in its entirety until its (re)construction in 2009 (see Elcott 2010). Haidee Wasson situates the avant-garde’s reinvention of exhibition space in relation to film and in the context of trying to “defy the static models that dominated in established museums” ( Chapter 26). The artists themselves often expressed the aims of these innovative installations in more explicitly political terms, wanting to jolt the visitor from “passivity” into (implicitly revolutionary) “activity.”

This idea of using installation to reinvent visitor activity also informed British pop artist Richard Hamilton’s pioneering exhibitions from the 1950s. The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London recently exhibited a reconstruction of an Exhibit (1957), the result of his collaboration with another artist, Victor Pasmore, and the critic Laurence Alloway. It consists of a room full of rectangular sheets of Perspex, suspended at different heights and angles and ranging in color and translucency from completely transparent to semitransparent coffee brown, dark red, yellow, and opaque black. Hamilton and his collaborators described an Exhibit as a game for the artists, who construct it improvisationally on site, according to predecided rules but without rehearsal: “Once the rules were settled, a high number of moves was possible ... an Exhibit as it stands, records one set of possible moves.” They suggest that, by entering the exhibit, visitors also participate in a game. 8Conceived in this way, the exhibition still has a structure, and its explicit content becomes something that is an implicit content of every exhibition: the moves and decisions of the visitors. This is the exhibition medium stripped down to its bare minimum. Nevertheless, visitors to the ICA in 2014 played a different game from visitors in 1957: armed with camera phones, many (including myself) photographed and videoed the installation.

Читать дальше