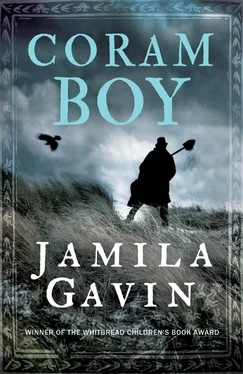

Otis and Meshak were in a queue of at least three drovers’ trains ahead of them, each with their thirty or so head of cattle, so they would be lucky to get across before nightfall.

‘Pots, pots, pans and pots, griddles and ladles, kettles and skillets, mugs and jugs, knives, forks and spoons, farming tools, all Cornish tin and Newcastle iron,’ Otis sang out in his trader’s patter.

‘The charity man’s here!’ A murmur went round. Word had gone on ahead that he was coming and some had waited for him.

In recent times, Meshak had got used to his father being called a ‘charity man’, though it had puzzled him. A wayfaring minister to whom they had once given a lift told him that in the Bible the word ‘charity’ meant ‘love’. It was true that a lucrative part of his father’s business as a travelling man was to collect abandoned, orphaned and unwanted children – many from local churches and poorhouses – and take them to the ever increasing number of mills that were springing up throughout the country. Otis always called the children ‘brats’ – as if, like rats, they were really vermin – but he made money out of them. Older boys, he handed over to regiments and naval ships, which were always on the lookout for soldiers and sailors to fight whatever wars were going on with the Prussians or the French abroad or the Jacobites up in the north. Down at the docks of London, Liverpool, Bristol and Gloucester, he made deals with ships who took both girls and boys to North Africa, the Indies or the Americas, along with their cargoes of slaves, cloth, timber and metal.

That may have been considered by some to be an act of charity, but Meshak wasn’t at all sure that it was love. He only had a vague idea about what love was. He thought he had been loved by his mother, though he could hardly remember her. She used to hug him and kiss him; she had played with him and told him stories. Then one day she had died and was gone for ever, and no one ever hugged or kissed him again, except for Jester – if you count face-licking, tail-wagging and jumping up a dog’s way of hugging and kissing. Meshak knew he loved his dog and that Jester loved him, but he would never have called that charity.

The children whom his father picked up on the open road or in small villages, towns and cities, and took into his wagon as an act of charity, never looked happy or grateful. They were usually handed over roughly, received roughly, fed little, beaten often. All in all, Meshak couldn’t say that either they, or indeed himself, were loved. If this was love, it was also business. Money changed hands, sometimes a lot of it.

But Meshak accepted that his father was a good and Christian man because everyone said he was. He was admired for this most Christian virtue, charity.

The sky was darkening not just with evening, but with a cloud bank of dark, purple rain expanding across the sky. A spiral of gulls circle-danced across the surface of the river; the evening light turned their white underbellies to silver. A few foresters and farming people converged eagerly on their wagon, bearing tools which needed sharpening, mending or exchanging.

Meshak knew what to do. He pulled back the flaps of the wagon and lifted out the pots and pans, knife-sharpeners, meat hooks, scissors, graters, mincers, goblets, griddles, knives and axes, as well as knick-knacks like combs and beads, bobbins and cottons, balls of string, trinkets and baubles. He spread out a large piece of sail cloth in a clearing by the side of the road and laid everything out so they could finger and question and calculate their terms for bargaining.

Meshak was up to dealing with simple transactions so, while he bartered, his father moved away in deep conversation with a well-dressed man, who led him into the cottage. He was not a wigged gentleman but a parish man with his hair drawn back under a broad-brimmed hat and wearing brown wool breeches and leather boots.

The skies darkened further and the first plops of rain thudded to earth. The queue for the ferry had shortened to just one wagon in front now, and Meshak had already repacked the wagon by the time Otis reappeared.

‘Get these brats in,’ he muttered. He referred to five solemn, poorly clad children in tow: a girl and a boy as young as three and five, who clutched each other’s hand tightly, and the rest – all boys – aged eight and nine years old. The children were silent, as though they had been born learning to stifle their fears. They allowed Meshak to herd them into the back of the wagon.

When the children were in place, tucked round the sides, still mute, still staring, Meshak and Otis began to separate the train of mules from the wagon. The ferryman was impatient now, looking anxiously at the stormy sky and the low sun, and urged them to hurry.

Otis tugged the reins down over the wagon mule’s ears and roughly cajoled it on to the ferry. The nervous animal resisted, unwilling to step on to the rocking craft, until a sharp stroke of the whip made it leap aboard with a clatter of hooves. Otis pulled a sack over the animal’s head to blinker it from the heaving water. He had just about cajoled a fourth mule on to the ferry when a woman’s voice called out softly, ‘Are you the Coram man?’

Meshak turned to see. He was surprised that his father reacted instinctively, as if that had always been his name. Meshak had never heard it before. Otis tossed Meshak the reins. ‘The boy will see them on,’ he yelled to the ferryman, and as Meshak took the reins and soothed the frightened mule, his father had already leapt ashore.

It was no housemaid or potato picker, like so many others who had hailed him, but a gentlewoman who, though trying to look modest and inconspicuous, was unmistakably a lady. Even had her refined voice not given her away, the cut and cloth of her cloak betrayed her. Her head was lowered into a basket, which she hugged tightly to herself, and she hung back in the shadows of the trees on the riverbank, trying not to be seen or identified.

The transaction was rapid. A heavy purse of money went into Otis’s pouch and he took the basket with a great show of reverence and concern, as if he would protect it with his life. Meshak heard the lady give one short, pitiful shriek of grief, quickly stifled. Otis leapt back on to the wagon and thrust the bundle into Meshak’s arms. ‘Look caring,’ he muttered, ‘till we’re on the other side.’

The ferry pulled away, but the woman continued to stand stiffly at the water’s edge, watching them. Meshak felt her eyes fixed on them all the way across. She was still standing there when they disembarked.

Chapter Two  The Black Dog

The Black Dog

The rain came down with a vengeance. The wind swished through the trees, making them bend and sway. The road turned to mire, and they still had two or three miles before they reached Gloucester city centre. The mules bowed their heads into the driving rain. The squeaks and mewlings in the sacks ceased. The wooden wheels ground along the deep, water-logged ruts, heavy with wet, sticky, clinging mud which sent out a spray with every turn and coated the dogs outside. Their legs kept running incessantly, also sending out muddy sprays; running, running, because they had no choice but to keep their legs moving, tied as they were to the axle. Jester was lucky; as Meshak’s dog he was allowed in the wagon.

Meshak pulled the flaps tightly shut to keep out the damp cold. The brats all looked at him with long, doleful glances as he snuggled up to Jester for warmth. He shut his eyes so as not to witness their despair. He felt hungry. They felt hungry. They were starving, probably hadn’t eaten since dawn. He didn’t want to know. Didn’t want to think about it. He had an apple in his pocket. He took it out with his eyes still closed and began to munch. He knew they were staring at him, their eyes huge with longing. He ate it as quickly as he could and fed the core to Jester. There was a shudder of repressed envy from the brats. They would have fallen eagerly on it and eaten every scrap if they could. Jester swallowed the core in a gulp.

Читать дальше

The Black Dog

The Black Dog