Akimbo knew that it would be impossible for him to do anything about the poachers in the reserve itself. The poaching gangs travelled by night, and were armed. Then they struck quickly and as quietly as possible, before fading away into the bush again. Every so often, the rangers picked up their tracks and pursued them, but usually they were too late.

He thought of different plans, but none of them seemed likely to work. If there was no point in his waiting for the poachers, why not go to the village and find them? That was the way to get the proof he would need to stop them.

At the edge of the rangers’ camp there was a storeroom. Akimbo had been inside only once or twice, as it was always kept locked, and his father rarely went there. In it were the things which the rangers confiscated from poachers when they managed to find them.

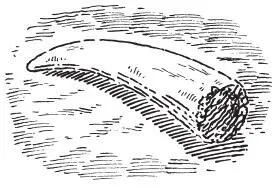

It was a grim collection. There were cruel barbed-wire traps, designed to tighten like a noose around an animal’s leg when it stepped into the concealed circle of wire. There were rifles, spears and ammunition belts. But what was saddest of all were the parts of animals which had been caught by the poachers. As well as horns and skins, there were the most sought-after trophies of all, the tusks of elephants.

Many of these things were kept to show to visitors, so that they could see what the poachers did. Some were also kept in the hope they would be needed as evidence once the poachers were caught. But that seemed to happen so rarely that the tusks and the traps just gathered more and more dust.

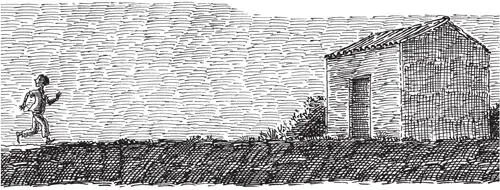

That night, at a time when the rest of the camp was asleep, Akimbo slipped out of his room and made his way across the compound towards the storeroom. In the moonlight he could make out the shape of the storeroom against the night sky. He paused in the shadows for a few moments, to check that nobody was about, and then he darted along the path to stand in front of the storeroom door.

His father’s bunch of keys was heavy in his pocket. He had slipped it out of the pocket of his father’s working tunic while his parents were busy in the kitchen. He had felt bad about that, but he told himself that he was not stealing anything for himself.

Now he tried each key in the storeroom lock. It was a slow business. In spite of the moonlight, there was still not enough light to see clearly, and it was difficult to keep those keys he had already used from being jumbled up with those which he had yet to try.

At one point he dropped the whole bunch, and it made a loud, jangly noise, but nobody woke up.

At last the lock moved, and with a final twist the bolt slid home. Akimbo pushed open the door and wrinkled his nose as he smelled the familiar, rotten odour of the uncured skins. But it was not skins he had come for. There, in a corner, was a small elephant tusk, which had been roughly sawn in two. Akimbo picked this up, checked that it was not too heavy to carry, and took it out of the storeroom. He took off its label. Then, locking the door again, he crept away, just like a poacher making off with his load of stolen ivory.

‘I’d like to go to the village,’ Akimbo told his parents the following morning.

Akimbo’s father seemed surprised.

‘Why? There’s nothing for you to do there.’

‘There’s Mato. I haven’t seen him for a long time. I’d like to see him. Last time I was there his aunt said that I could stay with them for a few days.’

His father shrugged his shoulders, looking at Akimbo’s mother.

‘If you want to go, I suppose you can,’ she said. ‘You’ll have to walk there, though. It’ll take three hours – maybe more. And don’t be any trouble for Mato’s aunt.’

Again Akimbo felt bad. He did not like to lie to his parents, but if he told them of his plan he was sure that they would prevent him from trying it out. And if that happened, then nobody would ever stop the poachers, and the hunting of the elephants would go on and on.

As his father had warned him, the walk was not easy. And, carrying a chunk of ivory in a sack over his shoulder, Akimbo found it even more difficult than he had imagined. Every few minutes he had to stop and rest, sliding the sack off his shoulder and waiting for his tired arm muscles to recover. Then he would heave the sack up again and continue his walk, keeping away from the main path to avoid meeting anybody.

At last the village was in sight. Akimbo did not go straight in, but looked around in the bush for a hiding place. Eventually he found an old termite hole. He stuffed the sack in it and placed a few dead branches over the top. It was the perfect place.

Once in the village, he went straight to Mato’s house. Mato lived with his aunt. She was a nurse and ran the small clinic at the edge of the village. Mato was surprised to see Akimbo, but pleased, and took him in for a cup of water in the kitchen.

‘I need your help,’ said Akimbo to his friend. ‘I want to find somebody who will buy some ivory from me.’

Mato’s eyes opened wide with surprise.

‘But where did you get it?’ he stuttered. ‘Did you steal it?’

Akimbo shook his head. Then, swearing his friend to secrecy, he told him his plan. Mato thought for a while and then he gave him his opinion.

‘It won’t work,’ he said flatly. ‘You’ll just get into trouble. That’s all that will happen.’

Akimbo shook his head.

‘I’m ready to take that risk.’

So Mato, rather reluctantly, told Akimbo about a man in the village whom everyone thought was dishonest.

‘If I had something stolen which I wanted to sell,’ he said, ‘I’d go to him. He’s called Matimba, and I can show you where he lives. But I’m not going into his house. You’ll have to go in on your own.’

Matimba was not there the first time that Akimbo went to the house. When he called an hour later, though, he was told to wait at the back door. After ten minutes or so the door opened and a stout man with a beard looked out.

‘Yes,’ he said, his voice curt and suspicious.

‘I would like to speak to you,’ Akimbo said politely.

‘Then speak,’ snapped Matimba.

Akimbo looked over his shoulder.

‘I have something to sell. I thought you might like it.’

Matimba laughed. ‘ You sell something to me ?’

Akimbo ignored the laughter.

‘Yes. Here it is.’

When he saw the ivory tusk sticking out of the top of Akimbo’s sack, Matimba stopped laughing.

‘Come inside. And bring that with you.’

Inside the house, Akimbo was told to sit on a chair while Matimba examined the tusk. He looked at it under the light, sniffed it, and rubbed at it with his forefinger. Then he laid it down on a table and stared at Akimbo.

‘Where did you get this?’ he asked.

Читать дальше