Secondary sonographic markers

While measurement of the NT combined with serum markers has been the mainstay of general population screening for many years, other sonographic features of aneuploidy have also been reported in the first trimester. Cystic hygroma is reported in about 1 of every 300 first‐trimester pregnancies, and refers to a markedly enlarged NT, often extending along the entire length of the fetus, with septations clearly visible. While it is not clear that a cystic hygroma is distinct from a markedly enlarged NT, this finding is associated with a 50% risk for fetal aneuploidy and in the remaining euploid pregnancies, almost half will be found to have major structural fetal malformations, such as cardiac defects and skeletal anomalies. Less than 25% of all cases of first‐trimester septated cystic hygroma or markedly enlarged NT (e.g., ≥6.5 mm) will result in a normal liveborn infant. Therefore, this finding should prompt immediate referral for CVS, and pregnancies found to be euploid should be evaluated carefully for other malformations with a detailed fetal anomaly scan and fetal echocardiography at 18–22 weeks of gestation, or in the first trimester if such evaluation is available.

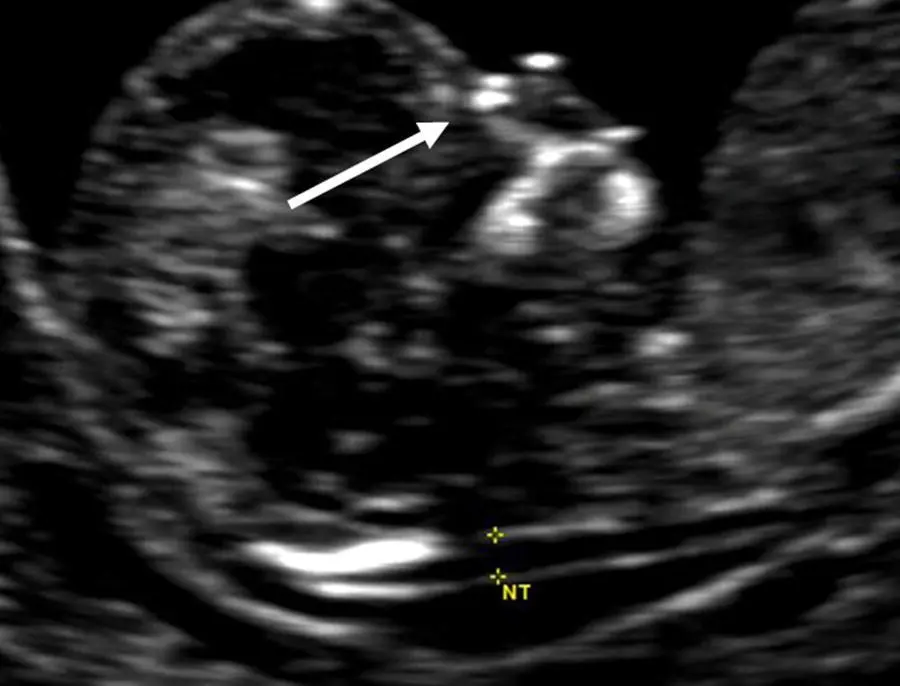

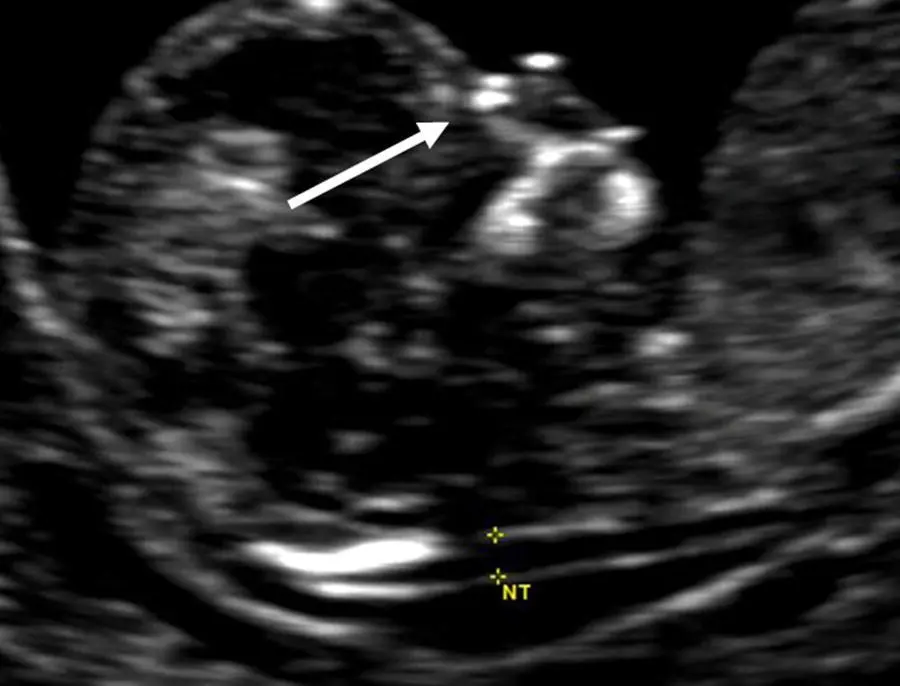

Figure 5.3 Nasal bone image of a euploid fetus at 13 weeks. Various features of good nasal bone technique are evident in this image: a good midsagittal plane, clear fetal profile, downward‐facing spine, slight neck flexion, and two echogenic lines, representing the overlying fetal skin and the nasal bone. The white arrow indicates the fetal nose bone, which loses its echogenicity distally.

Source: Mary E. Norton, MD.

Other sonographic features that have been reported to be useful in detection of trisomy 21 at 11–14 weeks include an absent nasal bone ( Figure 5.3), an abnormal Doppler blood flow pattern in the ductus venosus, and abnormal blood flow across the tricuspid valve with evidence of tricuspid regurgitation. However, studies suggesting a role for aneuploidy screening using these sonographic evaluations in the first trimester have been derived from select high‐risk populations, and likely overestimate the screening performance. At this time, while evaluation of the nasal bone can be useful for risk stratification in cases with enlarged nuchal translucency, first‐trimester evaluation of these other secondary markers is not recommended for general population screening.

Second‐trimester screening

Risk assessment for fetal trisomy 21 for many years involved primarily second‐trimester serum screening with maternal serum assay of alphafetoprotein (AFP), hCG, unconjugated estriol (uE3), and inhibin‐A (quad marker screening). In some practices, ultrasound assessment of features of aneuploidy, such as characteristic malformations or minor findings or markers, was used to assess or modify risk. Second‐trimester serum screening is now less commonly used due to the higher detection of first‐trimester combined or cfDNA screening, as well as the benefits of earlier detection. However, there is still a role for quad marker screening in patients who do not present for care until the second trimester.

Sonographic detection of major malformations

The genetic sonogram is a term that has been used to describe second‐trimester sonographic assessment of the fetus for signs of aneuploidy. The detection of certain major structural malformations that are known to be associated with aneuploidy should prompt an offer of genetic amniocentesis. Table 5.2summarizes the major structural malformations that are associated with the most common trisomies. Given the increasing popularity of first‐trimester screening, many advanced obstetric ultrasound practitioners have attempted to bring the genetic sonogram forward in gestation so that an anomaly scan may also be performed toward the end of the first trimester. Relatively limited data are available to validate the accuracy of the genetic sonogram in the first trimester for general population screening, and therefore the optimal time remains at about 18–22 weeks of gestation.

Table 5.2 Sonographic findings associated with trisomies 21, 18, and 13

| Trisomy 21 |

Trisomy 18 |

Trisomy 13 |

| Major structural malformations |

|

|

| Cardiac defects: |

Cardiac defects: |

Holoprosencephaly |

| • Atrioventricular (AV) canal defect |

• Double outlet right ventricle |

Orofacial clefting |

| • Ventricular septal defect |

• Ventricular septal defect |

Cyclopia |

| • Tetralogy of Fallot |

• AV canal defect |

Proboscis |

| Duodenal atresia |

Meningomyelocele |

Omphalocele |

| Cystic hygroma |

Agenesis of the corpus callosum |

Cardiac defects: |

| Hydrops fetalis |

Omphalocele |

• Ventricular septal defect |

|

Diaphragmatic hernia |

• Hypoplastic left heart |

|

Esophageal atresia Clubbed or rocker‐bottom feet Renal abnormalities Orofacial clefting Cystic hygroma Hydrops fetalis |

Polydactyly Clubbed or rocker‐bottom feet Echogenic kidneys Cystic hygroma Hydrops fetalis |

| Minor sonographic markers |

|

|

| Nuchal thickening |

Nuchal thickening |

Nuchal thickening |

| Mild ventriculomegaly |

Mild ventriculomegaly |

Mild ventriculomegaly |

| Short humerus or femur |

Short humerus or femur |

Echogenic bowel |

| Echogenic bowel |

Echogenic bowel |

Enlarged cisterna magna |

| Renal pyelectasis |

Enlarged cisterna magna |

Echogenic intracardiac focus |

| Echogenic intracardiac focus |

Choroid plexus cysts |

Single umbilical artery |

| Hypoplastic nasal bones |

Micrognathia |

Overlapping fingers |

| Brachycephaly |

Strawberry‐shaped head |

Growth restriction |

| Clinodactyly |

Clenched or overlapping fingers |

|

| Sandal gap toe |

Single umbilical artery |

|

| Widened iliac angle |

Growth restriction |

|

| Growth restriction |

|

|

When a major structural malformation is found, such as an atrioventricular canal defect or a double‐bubble suggestive of duodenal atresia, the risk of trisomy 21 in that pregnancy is increased by approximately 20–30‐fold. For many patients, such an increase in their background risk for aneuploidy will be sufficiently high to justify genetic amniocentesis.

Sonographic detection of minor features of aneuploidy

Second‐trimester sonography can also detect a range of minor features or “markers” suggestive of aneuploidy. These are not structural abnormalities of the fetus per se but are associated with an increased probability that the fetus is aneuploid. These minor markers are typically much more common than structural abnormalities and likelihood ratios based on the presence or absence of these markers have been used to adjust each patient’s risk of having a fetus with trisomy 21. However, with improvements in aneuploidy screening, including serum and combined methods as well as cfDNA screening, these minor findings add little to the detection of chromosomal abnormalities. Rather, when screening results indicate a low risk of aneuploidy, these markers are most commonly normal variants. The one possible exception is a thickened nuchal fold, which is uncommon in euploid fetuses and therefore has a low false‐positive rate and relatively high specificity for Down syndrome. In cases in which multiple markers are seen, the risk of aneuploidy is higher and genetic counseling may be indicated. Table 5.2also summarizes the minor sonographic markers that, when visualized, may increase the probability of an aneuploid fetus.

Читать дальше