So let’s take a closer look at how our current ideas about ‘normal’ took shape. In nineteenth-century Britain, a regular working day ranged from 10 to 16 hours, typically for six days a week. From the midnineteenth century onwards, workers on both sides of the Atlantic campaigned for a ‘just and sufficient’ limit to their hours of labour. The eight-hour movement gathered strength, and workers came out in their thousands to demand ‘eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will’. 7Karl Marx maintained that shortening the working day was a ‘basic prerequisite’ of what he described as the ‘true realm of freedom’, 8and this became a central issue for socialist and labour movements in industrialized countries across the world.

In 1856, stonemasons in Melbourne, Australia, fought successfully for an eight-hour working day – a global first. 9In 1889, gas workers in East London became the first to do so in Britain. In 1919, the nascent International Labour Organization (ILO) set out its Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, establishing the principle of an eight-hour day, or 40-hour week, which has since been ratified by 52 countries. 10

In 1926 the US Ford Motor Company was one of the first major employers to adopt a five-day, 40-hour week for workers in their factories – with no reduction in pay. Productivity increased and the corporation went from strength to strength. 11In 1930, the cereal magnate W. K. Kellogg replaced three daily eight-hour shifts at his plant in Battle Creek, Michigan, with four six-hour shifts. Results included big cuts in absenteeism, turnover and labour costs, and a 41 per cent reduction in workplace accidents. 12

Franklin D. Roosevelt launched his ‘President’s Re-employment Agreement’ in 1933, urging US employers to raise hourly wages and cut the length of the working week to 35 hours. Roosevelt shared the view of UK economist John Maynard Keynes that government spending could stimulate the economy and that there was a strong relationship between higher productivity and shorter hours of work. He hoped to get more people back into work and – by raising wages at the same time – boost consumption and growth. Firms readily signed up, and between 1.5 million and 2 million new jobs were created.

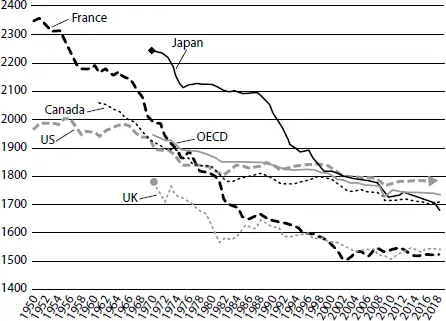

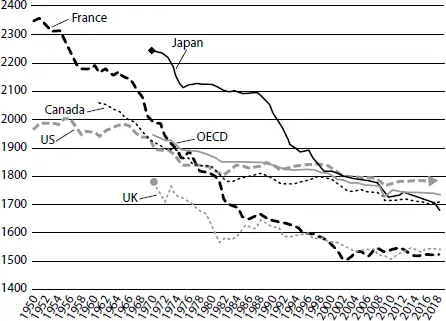

A combination of industrial struggles and government initiatives ensured that the two-day weekend and the 40-hour week were widely adopted as standard by the middle of the twentieth century. But it wasn’t all plain sailing. Average working hours continued to fall, as Figure 1 indicates, but less steeply from the 1980s. After that, the trend flattened in many countries and in some went into reverse.

In 1930, Keynes famously predicted that a 15-hour week would be the norm by the twenty-first century – how wrong he was! What happened to put a brake on progress towards reduced working time? A combination of economic and cultural developments have locked us into the eight-hour day norm.

Figure 1: Average annual hours actually worked per worker, 1950–2018, all G7 countries with data pre-1971 and the OECD average.

Source: OECD https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AVE_HRS

When Keynes made his ill-fated prediction, he assumed that economy-wide labour productivity – that is, gross domestic product (GDP) per hour worked – would rise to a level that enabled society’s needs to be met while everyone spent far fewer hours in paid employment. He anticipated an era of ‘material abundance’, bringing with it a challenge to ensure that it would ‘yield up the fruits of a good life’.

For three decades following the Second World War, productivity did indeed rise quickly. At the same time, collective bargaining played a prominent role in the wider economy; so too did public sector coordination. Partly as a result of this, gains from productivity growth were more evenly distributed across society, in terms of both rising pay and falling average working hours.

But from the 1980s, the rules governing advanced economies began to change. Rates of growth in labour productivity started to fall as overall levels of investment by firms and governments receded. The composition of industry also started to shift, with a decline in manufacturing and a rise of the service sector. Information and communications-based technology became increasingly dominant, but appeared to have lower marginal gains for measurable GDP growth than the improvements in manufacturing and production seen in earlier decades.

The economic pie was increasing more slowly overall. More crucially still, a larger share of it started to shift towards property owners and shareholders at the expense of workers. The capacity of trade unions to bargain for better pay and conditions was undermined, most notably in the UK during the 1980s but in other countries and decades as well. Overall, pay increased at even slower rates compared with returns on wealth. The average level of unemployment rose significantly. Income inequality rose to unprecedented post-war heights across Europe and North America, and then stubbornly remained high through various manifestations of both ‘left’ and ‘right’ governments across different countries. The rate of progress towards more leisure time slowed down conspicuously.

The 2008 financial crisis fired the starting gun for a third major post-war evolution in power and reward across advanced economies. In the UK, for example, the long-run rate of productivity growth has dropped by two-thirds since 2008. This has been both cause and effect of a marked increase in low-paid, insecure work and a period of weak pay increases without precedent in modern records. One in six workers in the UK (more than five million people) are experiencing low pay alongside some form of insecurity at work; 13many are trapped in a revolving door between low pay and no pay at all. Meanwhile, in many other countries – notably in Southern Europe – unemployment remains very high. Alongside these disturbing trends, reductions in the average working week have stalled since 2008 for the longest period since before the Second World War.

Behind all this, a powerful confluence of ideas has shaped prevailing attitudes about what is ‘right’ as well as ‘normal’. In 1926 – the same year Ford Motor Company introduced the five-day 40-hour week – Judge Elbert H. Gary, board chairman of the United States Steel Corporation, told the New York Times that the five-day week was impractical, uncompetitive and illogical, not only for steel workers, but for any other business. ‘The commandment says, “Six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work.” The reason it didn’t say seven days is that the seventh day is a day of rest and that’s enough.’ 14

Judge Gary’s aversion to shorter hours drew on something much deeper than fear of commercial risk. He subscribed to a widely held belief that work was the God-given purpose of humankind. Where labour was brutal and coercive – as it so often was – it was helpful to distinguish between body and mind, as Descartes had suggested. 15For if humans were made ‘in the image of God’, then their Godlike essence could be safely located in the mind (or soul), which may be separate and immortal, leaving the mortal body to be honed and disciplined into a machine for the mines, mills and factories of industrial capitalism.

The mechanical clock was a vital component of that discipline. As clockwork became more reliable and widely used, it set the scene for what Marx identified as the commodification of time and what British historian E. P. Thompson described as the birth of ‘industrial time consciousness’. 16Industry required its human machines to operate predictably and reliably, in ways that could be measured, bought and sold.

Читать дальше