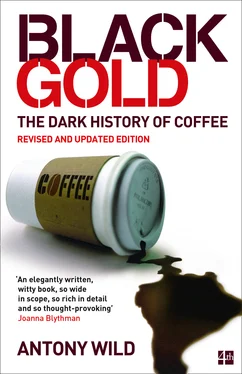

Many of the momentous events and grand personages of world history have scratched ghostly messages on the black basalt of St Helena, and deciphering them in this isolated context conveys a curious sense of the underlying connectedness of the island with the pivotal phenomena of that larger world. Thus da Nova’s fleet was returning from India, where the Portuguese were starting to build a trading empire that was to dominate the Indian Ocean for the next century; the East India Company was threatening to usurp that empire by the time it took possession of the island in 1659; the Dutch and French success with growing coffee in their colonies outshone that of the Company, whose neglected seedlings were buffeted by the southern trade winds; Napoleon had introduced to Europe the drinking of chicory as a coffee substitute under his ‘Continental System’ and, during his exile, he planted a coffee tree in his garden that died from exposure to those same winds; the island became a refuge for captured slave ships after abolition and one such was on its way to Brazil, where slavery was the cornerstone of that country’s coffee industry …

The 5000-strong population of St Helena has been used recently as a kind of Petri dish by sociologists wishing to study the effects of television – introduced only in the last few years – on everything from crime rates to Girl Guide membership. In this book, the island will also be used as a Petri dish: we will return to it repeatedly to study how the history of coffee and colonialism evolved together over the last five hundred years to forge an unholy alliance that still exists for the benefit of Western coffee consumers at the expense of the people of the Third World countries – more often than not former colonies – that produce it, and of the planet itself.

In 1991 I bought a small one-kilo bag of coffee, and the press coverage that generated was phenomenal.

‘He’s a pioneer among coffee traders’, the then-young tyro journalist Nigel Slater wrote, moderately enough; ‘The Indiana Jones of the coffee world’, campaigning food writer Joanna Blythman said, upping the ante – I could scarcely complain about that flattering comparison; but then … ‘The Christopher Columbus of coffee …’ I’d had an inkling that introducing the now infamous kopi luwak to the Western world would sprinkle a bit of magic PR dust, but I’d hardly expected to be compared to the leading light of the Golden Age of Exploration.

During my time as the Coffee Director for Taylors of Harrogate in the 1980s and early 90s, most of my suppliers in Europe used to look at me with quizzical amusement when I kept asking them to source me bizarre coffees they’d never heard of. Usually I had to jump on a plane to Yemen or Cuba or wherever to track down my quarry myself. But in the case of kopi luwak …

It happened like this. I’d spent most of 1981 in London serving my coffee taster’s apprenticeship with various City merchants, and I passed some of my spare time researching in the library of the International Coffee Organization. One day I pulled a back copy of National Geographic magazine off the shelf. In it I found a full-length feature about Sumatran coffee, and one paragraph caught my eye – a reference to the author being served a sublime coffee made from beans that had been digested in the stomach of a small weasel-like wild animal called a luwak . These luwaks prowled the plantations at night selecting to eat, in time-honoured fashion, ‘only the finest, ripest coffee cherries’, which were then digested by the animal, evacuated, collected, washed and roasted. I mentally filed this curious tale and forgot about it, until nearly ten years later when I was on the phone with a particularly persistent Swiss coffee trader who was trying as usual to sell me some coffee that I didn’t need. ‘Get me some kopi luwak , ’ I said to distract him, ‘I’ll buy that …!’ I explained to him exactly what it was, and where it was to be found: he had been duly amazed and amused, and I had thought no more about it. Three months had passed when he called to announce, ‘Mr Wild! I have a kilo of kopi luwak for you!’

Of all the remarkable coffees I had ever bought, this small bag of kopi luwak generated the most interest by far. The press and public couldn’t get enough of the story. I found out, to my amazement and shock, that what had been once an almost unheard-of delicacy that I had introduced more or less on a whim had become the must-have coffee on the books of many aspiring specialist green coffee trading companies both in Europe and the United States. It had even made an appearance in a Hollywood film; in The Bucket List, a terminally ailing Morgan Freeman brings some for a similarly ailing Jack Nicholson to taste.

As a consequence of all this attention, demand for kopi luwak had soared, and to meet it, wild luwaks were being coaxed onto Sumatran coffee farms to gorge themselves on coffee cherries and produce more crap. An American company had artificially synthesised the flavour imparted by this unorthodox ‘processing’ and licensed a roaster to use it. Far from recoiling in horror, discerning consumers at that time were falling over themselves to taste kopi luwak. A long way from the days when I was the only one willing to drink it, I thought almost fondly, dazzled by the success of my protégé, and wondering idly how this demand was met by the 500 kilos the roasters still proclaimed were collected in the wild each year.

Many other aspects of today’s speciality coffee market amaze me, too. The coffees that I introduced to the startled British public for the first time twenty-five years ago – St Helena Island, Yemeni Mocha Matari, Jamaica Blue Mountain Peaberry, Cuba Crystal Mountain and Harrar Longberry – would now appear really quite run-of-the-mill to the so-called ‘Third Wave’ coffee traders and roasters, focused as they are on individual plantations and plant varietals, along with exceptional husbandry and processing. And they have developed a range of coffee vocabulary far beyond that with which I was apprenticed, to go with their expertise.

But in one respect little has changed since this book was first published: the myths about the history of the coffee trade that are endlessly repeated and recycled by the trade itself are as flawed and derivative as they ever were. When this book was first published in 2003, one of my aims was, as far as possible, to set the historical record straight. The first edition of this book was published in the UK and USA, and translated into Chinese, Japanese, French, Turkish and Vietnamese, so it was hardly an obscure tome. Yet it is still possible to read abject nonsense about the history of coffee on a million coffee trade websites as though its true heritage had never existed. It seems that all the care and attention to detail that is lavished on the other aspects of the coffee trade goes out of the window when it comes to discussing its roots in our past. No one, for example, even seems to have noticed the significance of the find at Kush mentioned in the last chapter.

The book also concerns the economic, environmental and political aspects of the coffee trade. When I was first writing it in 2001/2, world coffee prices were at an all-time low and the human suffering this caused to those working at the most basic level of the trade was immense. Some critics called the approach I took in this book anti-corporate and anti-capitalist, and back then, when economies in the developed world were booming, such an approach was distinctly unfashionable. We live in a very different world to that following the economic crash of 2008, and since then the capitalist model has been under question in a way it has rarely been before. In my pioneering coffee days I was said to be ahead of my time: unfortunately it seems that, with regard this book, my time has finally come, and what I forecasted back then with some foreboding is actually happening now.

Читать дальше