A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78630-631-9

Foreword

Mankind and deserts

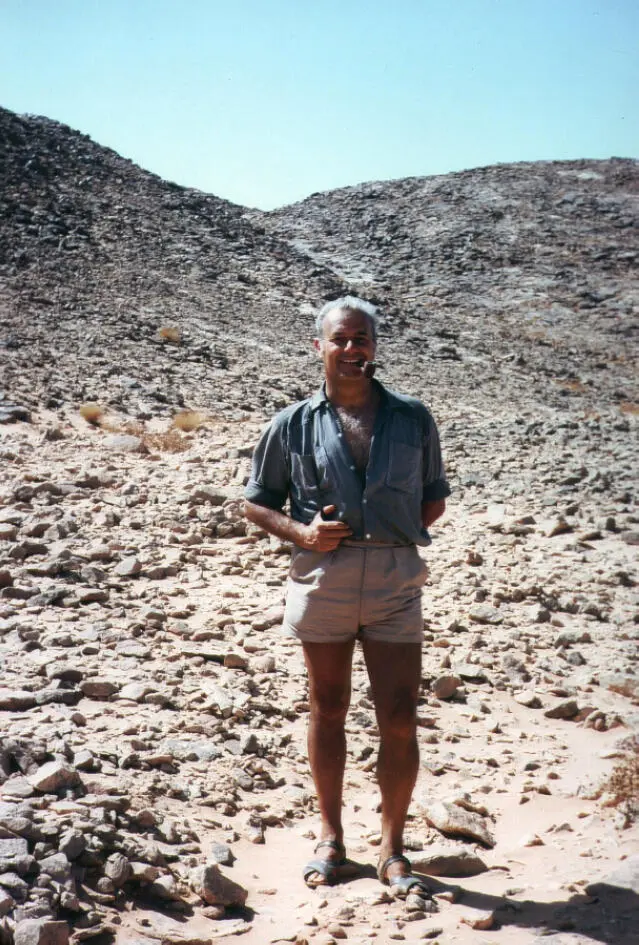

Fernand Joly 1departed from this world before he was able to complete this book, through which he had hoped to share his experiences of and passion for deserts.

“Yet another book on deserts!” some might think; another book to add to the numerous publications dedicated to these alien and fascinating worlds.

This book, however, is different from earlier books, as can be seen from its title “ Mankind and Deserts”. It is based on the singular relationships that are formed between humans and the world of the desert – relationships that are unique because they can be traced back to the very origins of humanity. Indeed, it is from the arid Horn of Africa (East Africa) that large migrations began and it is along the deserts, if not within the deserts themselves, that we find the major cradles of burgeoning historical civilizations. This inhospitable world is also associated with great spiritual leaders such as Moses, Jesus, Mohammed and the Buddha, while serving as the backdrop for adventurers and empire builders from Alexander the Great to Genghis Khan, or from the Incans to the Conquistadors in the Andes and Mexico.

What is this universe that is so barren and yet so mesmerizing?

“ All about a word” was how Fernand Joly introduced his book: “ What is a desert?” The ambiguity in this word results from the fact that it has been used in different senses across literature and throughout history. For a geographer-writer such as Fernand Joly, the one fact that stood out was that there was no one desert; instead there were multiple deserts , diverse and varied, ranging from Death Valley to the Kalahari, from the Namib to the Atacama or the Gobi desert. Each of these is a unique landscape, whose uniqueness was born out of its position with respect to the general atmospheric circulation, its geographic location with respect to the sea and to its relief features. And yet, transcending all differences, there is one constraint that binds them all together: aridity, defined as a natural physical state characterized by persistent dryness with the corollary of extremely scarce water resources. Both these concepts, aridityand water, are at the heart of the following chapters. Aridity ( Chapter 3) because it “transcends time and takes over space” and water (Volume 2, Chapters 1– 3) because it is the essential resource for all life, especially in the desert. Aridity is distinct from “drought”, which is simply a “period with insufficient rainfall”. Water is seen through the lens of how it appears on land: “wild water”, which flows over slopes in an un-channeled manner (Volume 2, Chapter 1), under the impact of violent but brief downpours, and “concentrated waters”, i.e. waters “concentrated” into a channel, fed by distant precipitation upstream of the borders of the desert. As can be seen, there is in fact a true hydrography of the arid world. Satellite images, among other sources, offer us clear and accurate reproductions of these systems: fossil hydrographic networks , the legacy of ancient humid periods, a map of intermittent water bodies (Volume 2, Chapter 2): playas and sabkhas , permanent lakes with fluctuating shorelines, such as Lake Chad or Lake Eyre, or large allogenous rivers (Volume 2, Chapter 3) that are born outside the desert but travel through the desert, sustaining life, such as the Colorado, the Niger and the Nile, “the first and most remarkable of rivers in the arid world”.

The role played by salts in hot deserts is rarely discussed in a systematic manner. Guilhem Bourrié, geochemist and soil scientist at INRAE, has analyzed the origins and nature of these salts and demonstrated how important these salt deposits in the desert are for humans, whether they live off agriculture, livestock or, indeed, the salt trade (Volume 2, Chapter 4).

Chapter 1of Volume 3, drafted by Joly, was edited after his demise by Yann Callot, a professor at the University Lyon 2 who is a specialist in ergs and dunes. This chapter examines the importance of windin the desert. Wind, sometimes considered to be more emblematic of a desert than even dryness, counts among the earliest dynamics on Earth, an element that humans have not always been able to control. Indeed, this lack of understanding of wind has sometimes had disastrous consequences for certain projects (see the Green Dam in Algeria).

The final chapter in Volume 3, “ Living in the Desert”, was taken up by Marc Côte, Professor Emeritus at the University of Provence, who worked as a professor for 20 years at the University of Constantine. He has drawn on his deep knowledge of the land and the people of the Saharan region to present what he calls “The Desert Civilization”.

Finally, it must be noted, with great regret, that, since 2010, “geopolitical turbulences have tended to change the fundamentals, to burn away knowledge and to prevent researchers from keeping in touch with this part of space and humanity.”

Most of the illustrations were refined by Éliane Leterrier.

Yvette DEWOLF

Honorary Professor at the University Paris VII, Denis Diderot

Paris

October 2020

A man in the desert: Fernand Joly Tademaït, Sahara, Algeria

1 1 Professor at the University Paris VII, Denis Diderot, who spent 15 years at the Moroccan Institute of Science in Rabat.

Introduction: Water in Deserts

Because of the minuscule amounts of water and their meteoric variability, the discipline of arid zone hydrology is one of the highest forms of art and science.

V. Kotwicki, Floods of Lake Eyre

“Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…” ( “What makes the desert beautiful,” said the Little Prince, “is that somewhere it hides a well…” )

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

It is because of its extreme scarcity, or indeed its absence, that water is so important in a desert, even when it is invisible, when one is searching for it or it is altogether lacking. It is exceptional to find open water sources (there are long periods when these open water bodies simply do not exist) and they are most often found at some depth. Finding water, collecting it, transporting it, using it carefully and storing it are all key issues to be resolved in desert life. Sometimes there is a lack of water because the excessive aridity results in deficient hydrology and a lack of wild water (Joly 2006), while at other times there is a poorly developed hydraulic system, such that domesticated water resources (Prosper-Laget 2001) cannot fulfill the needs of the population they serve.

Sometimes the areas involved are vast, like the Sahara, Arabia or central Australia; and, sometimes, there are smaller spaces where water, though present, is unequally distributed, as is the case in central Asia, Mongolia, western North America and the Andes. The tragedy here is that across these regions there is a permanent imbalance between available water resources (highly limited) and the requirements of the ecosystem for ordinary consumption and development (Margat and Tiercelin 1998).

I.1. Hydrology – wild water

Hydrology is the science of water (Cosandey and Robinson 2000) and it is not a discipline that can be easily applied to deserts (Margat 1985). As with climatological data, this scientific field is hindered by a series of restrictions, arising, principally, from small human presence and the highly discontinuous nature of hydrological phenomena, which are scattered through time as well as space. There are, of course, a relatively large number of qualitative observations from nomads and travelers. However, these are often not very objective, difficult to access and unreliable. The quantitative observations that are archived are better monitored and valid, but they are far too scattered as they usually focus on inhabited sites: military or administrative stations, oases, mining or agricultural installations and construction sites.

Читать дальше