As a composer, Handel was great in all styles—from the familiar and airy to the grand and sublime. His instinctive taste for melody, and the high value he set on it, are obvious in all his works; but he felt no less strongly the charms of harmony, in fulness and richness of which he far surpassed even the greatest musicians who preceded him. And had he been able to employ the variety of instruments now in use, some of which have been invented since his death, and to command that orchestral talent, which probably has had some share in stimulating the inventive faculty of modern composers, it is reasonable to suppose that the field of his conceptions would have expanded with the means at his command. Unrivalled in sublimity, he might then have anticipated the variety and brilliance of later masters.

Generally speaking, Handel set his words with deep feeling and strong sense. Now and then he certainly betrayed a wish to imitate by sounds what sounds are incapable of imitating; and occasionally attempted to express the meaning of an isolated word, without due reference to the context. And sometimes, though not often, his want of a complete knowledge of our language led him into errors of accentuation. But these defects, though great in little men, dwindle almost to nothing in this “giant of the art:” and every competent judge, who contemplates the grandeur, beauty, science, variety, and number of Handel’s productions, will feel for him that admiration which Haydn, and still more Mozart, was proud to avow, and be ready to exclaim in the words of Beethoven, “Handel is the unequalled master of all masters! Go, turn to him, and learn, with such scanty means, how to produce such effects!”

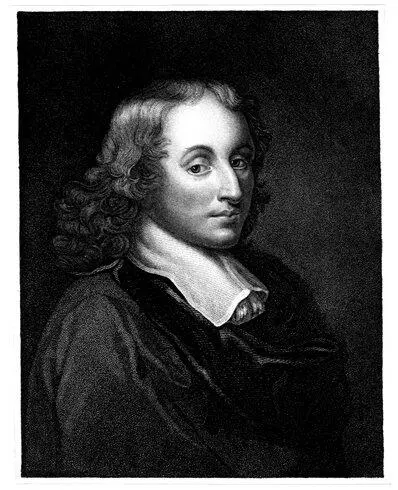

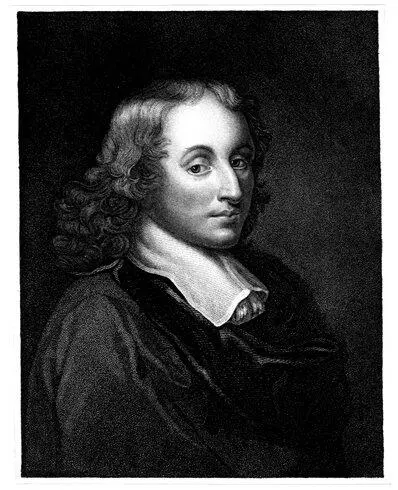

Engraved by H. Meyer. PASCAL. From the original Picture by Philippe de Champagne, in the possession of M. Lenoir at Paris. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London, Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Blaise Pascal was born June 19, 1623, at Clermont, the capital of Auvergne, where his father, Stephen Pascal, held a high legal office. On the death of his wife in 1626, Stephen resigned his professional engagements, that he might devote himself entirely to the education of his family, which consisted only of Blaise, and of two daughters. With this view he removed to Paris.

The elder Pascal was a man of great moral worth, and of a highly cultivated mind. He was known as an active member of a small society of philosophers, to which the Academie Royale des Sciences, established in 1666, owed its origin. Though himself an ardent mathematician, he was in no haste to initiate his son in his own favourite pursuits; but having a notion, not very uncommon, that the cultivation of the exact sciences is unfriendly to a taste for general literature, he began with the study of languages; and notwithstanding many plain indications of the natural bent of his son’s genius, he forbad him to meddle, even in thought, with the mathematics. Nature was too strong for parental authority. The boy having extracted from his father some hints as to the subject matter of geometry, went to work by himself, drawing circles and lines, or, as he called them in his ignorance of the received nomenclature, rounds and bars, and investigating and proving the properties of his various figures, till, without help of a book or oral instruction of any kind, he had advanced as far as the thirty-second proposition of the first book of Euclid. He had perceived that the three angles of a triangle are together equal to two right ones, and was searching for a satisfactory proof, when his father surprised him in his forbidden speculations. The figures drawn on the walls of his bed-chamber told the tale, and a few questions proved that his head had been employed as well as his fingers. He was at this time twelve years old. All attempts at restriction were now abandoned. A copy of Euclid’s Elements was put into his hands by his father himself, and Blaise became a confirmed geometrician. At sixteen he composed a treatise on the Conic Sections, which had sufficient merit to induce Descartes obstinately to attribute the authorship to the elder Pascal or Desargues.

Such was his progress in a study which was admitted only as the amusement of his idle hours. His labours under his father’s direction were given to the ancient classics.

Some years after this, the elder Pascal had occasion to employ his son in making calculations for him. To facilitate his labour, Blaise Pascal, then in his nineteenth year, invented his famous arithmetical machine, which is said to have fully answered its purpose. He sent this machine with a letter to Christina, the celebrated Queen of Sweden. The possibility of rendering such inventions generally useful has been stoutly disputed since the days of Pascal. This question will soon perhaps be set at rest, if it may not be considered as already answered, by the scientific labours of an accomplished mathematician of our own time and country.

It should be remarked that Pascal, whilst he regarded geometry as affording the highest exercise of the powers of the human mind, held in very low estimation the importance of its practical results. Hence his speculations were irregularly turned to various unconnected subjects, as his curiosity might happen to be excited by them. The late creation of a sound system of experimental philosophy by Galileo had roused an irresistible spirit of inquiry, which was every day exhibiting new marvels; but time was wanted to develope the valuable fruits of its discoveries, which have since connected the most abstruse speculations of the philosopher with the affairs of common life.

There is no doubt that his studious hours produced much that has been lost to the world; but many proofs remain of his persevering activity in the course which he had chosen. Amongst them may be mentioned his Arithmetical Triangle, with the treatises arising out of it, and his investigations of certain problems relating to the curve called by mathematicians the Cycloid, to which he turned his mind, towards the close of his life, to divert his thoughts in a season of severe suffering. For the solution of these problems, according to the fashion of the times, he publicly offered a prize, for which La Loubère and our own countryman Wallis contended. It was adjudged that neither had fulfilled the proposed conditions; and Pascal published his own solutions, which raised the admiration of the scientific world. The Arithmetical Triangle owed its existence to questions proposed to him by a friend respecting the calculation of probabilities in games of chance. Under this name is denoted a peculiar arrangement of numbers in certain proportions, from which the answers to various questions of chances, the involution of binomials, and other algebraical problems, may be readily obtained. This invention led him to inquire further into the theory of chances; and he may be considered as one of the founders of that branch of analysis, which has grown into such importance in the hands of La Place.

His fame as a man of science does not rest solely on his labours in geometry. As an experimentalist he has earned no vulgar celebrity. He was a young man when the interesting discoveries in pneumatics were working a grand revolution in natural philosophy. The experiments of Torricelli had proved, what his great master Galileo had conjectured, the weight and pressure of the air, and had given a rude shock to the old doctrine of the schools that “Nature abhors a vacuum;” but many still clung fondly to the old way, and when pressed with the fact that fluids rise in an exhausted tube to a certain height, and will rise no higher, though with a vacuum above them, still asserted that the fluids rose because Nature abhors a vacuum, but qualified their assertion with an admission that she had some moderation in her abhorrence. Having satisfied himself by his own experiments of the truth of Torricelli’s theory, Pascal with his usual sagacity devised the means of satisfying all who were capable of being convinced. He reasoned that if, according to the new theory, founded on the experiments made with mercury, the weight and general pressure of the air forced up the mercury in the tube, the height of the mercury would be in proportion to the height of the column of incumbent air; in other words, that the mercury would be lower at the top of a mountain than at the bottom of it: on the other hand, that if the old answer were the right one, no difference would appear from the change of situation. Accordingly, he directed the experiment to be made on the Puy de Dôme, a lofty mountain in Auvergne, and the height of the barometer at the top and bottom of the mountain being taken at the same moment, a difference of more than three inches was observed. This set the question at rest for ever. The particular notice which we have taken of this celebrated experiment, made in his twenty-fifth year, may be justified by the importance attached to it by no mean authority. Sir W. Herschell observes, in his Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy, page 230, that “it tended perhaps more powerfully than any thing which had previously been done in science to confirm in the minds of men that disposition to experimental verification which had scarcely yet taken full and secure root.”

Читать дальше