After having lived thirty years in this retirement, the great Sully expired at his Château of Villebonne, in the eighty-second year of his age, on the 22d December, 1641—the same year in which Lord Strafford, the minister of Charles I., was beheaded in London, and in which the grave closed over the widow of Henry IV., Mary de’ Medici, who died at Cologne in obscurity and great poverty.

It is to be regretted that no author has yet produced a life of Sully worthy of the subject. The ‘Economies Royales’ is the great storehouse of information, but its prolixity and singularity of style render it little attractive to the general reader. The following works, however, may be consulted:—’Les Vies des Hommes Illustres de la France,’ by M. D’Auvigny, and the memoir in the ‘Biographie Universelle.’

4. Mémoires de Sully.

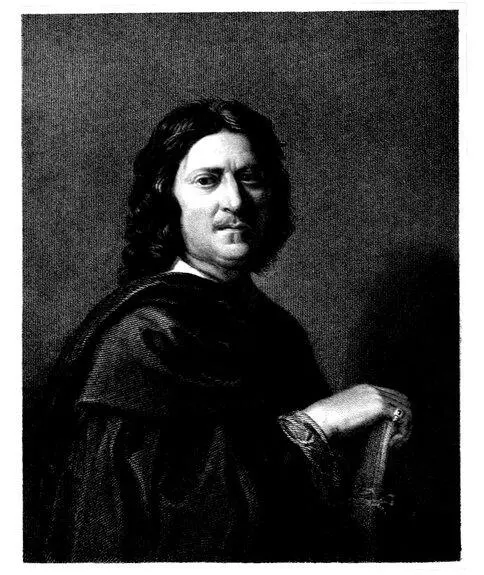

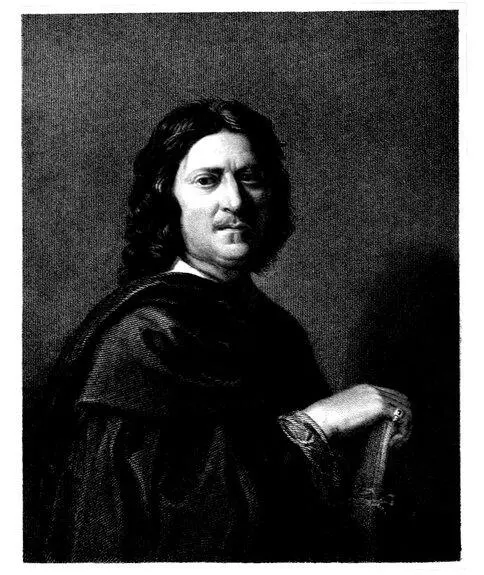

Engraved by J. Posselwhite. N. POUSSIN. From the original Picture by himself in the Gallery of the Louvre. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Truth and compliment are happily united in Poussin’s observation to a noble amateur, “You wanted but the stimulus of necessity to have become a great painter.” The artist had himself felt this stimulus, and he knew its value in producing resolution and habits of industry. His family was noble, but indigent: John, his father, a native of Soissons, and a soldier of fortune, served during the reigns of Charles IX., Henry III., and Henry IV., with more reputation than profit. At last, finding that in the trade of arms his valour was likely to be its own reward, he married the widow of a solicitor, resigned his military employments, and fixed his abode at Andelys in Normandy, where, in June 1594, his son Nicholas, the subject of the present memoir, was born.

The district in which Andelys is situated is remarkable for its picturesque beauty, and from the scenery which surrounded him the genius of Poussin drew its first inspiration. His sketches of landscape attracted the notice and commendation of Quintin Varin, an artist residing in the neighbourhood. Animated by praise, young Poussin earnestly solicited his father that he might become Varin’s pupil: a request to which the prudent parent, after long hesitation, reluctantly acceded. He knew that in such a pursuit as that of the fine arts, much of the aspirant’s life must be expended before a just estimate of his professional talents can be formed, and that even where talent exists, the success of the possessor is not always commensurate to its claims. The youth, however, was fortunate in meeting, in the first instance, with a preceptor whose instructions, founded on just principles, left him nothing to unlearn. He remained with Varin until his eighteenth year, when he went to Paris, and studied under Ferdinand Elle, and L’Allemand, two artists then in fashion, from whom he learned nothing. In the mean time he had become acquainted with several persons who appreciated his dawning talents, and felt an interest in his fortunes. Among the rest, a young nobleman of Poitou manifested an almost fraternal attachment towards him, relieved his pecuniary wants, and among other services introduced him to Courtois, the King’s mathematician, who possessed a fine collection of prints by Marc Antonio, and a great number of drawings and sketches by Raffaelle, Giulio Romano, and other great masters of the Roman school. These treasures Poussin studied and copied with sedulous zeal and attention, and he was frequently heard to advert to this circumstance as one of the most fortunate of his life, inasmuch as the contemplation of these fine examples had fixed his taste, and determined the bent of his powers towards the higher branches of art, at a time when his mind was fluctuating between the attractions of different schools.

The young Poitevin, being summoned to return home, invited Poussin to become his companion, and to undertake a series of pictures, calculated, by its extent as well as its excellence, to do honour to his paternal mansion. But his mother regarded the fine arts and those who patronised them with equal and unqualified contempt: and suffering in her house the exercise of none but what she considered useful talents, she assigned to Poussin the office of house-steward, and his visions of fame were at once dispelled by the humble occupation of overlooking the servants, and keeping accounts. It may easily be supposed that the young artist did not deport himself very meekly under the new appointments which had thus unexpectedly been thrust upon him. Without asking the sympathy or assistance even of his friend, who, it would appear, had acquiesced too readily in his mother’s arrangements, he quitted the house and made his way to Paris on foot; having no other means of support on the road than the extemporaneous productions of his pencil. In consequence of the hardships which he experienced during this journey, he was attacked by a fever on reaching Paris, which obliged him to return to Andelys. After the lapse of a year, having recruited his health, he made arrangements to execute a long-cherished purpose of a journey to Rome. But with an improvidence not uncommon in artists, and sometimes falsely said to be characteristic of genius, he calculated his resources so inaccurately that in two successive attempts he was obliged to return, leaving his purpose unaccomplished. In the first instance he reached Florence, but in the second, he got no farther than Lyons. The disappointment, however, was attended with good results, for on his return to Paris, a circumstance occurred which at once raised him into high reputation.

The Jesuits had ordered a set of pictures for a high festival, which were to display the miracles worked by their patron saints, Ignatius Loyola, and Francis Xavier. Of these, six were executed by Poussin, in a very short space of time; the pictures were little more than sketches, but they exhibited such powers of composition and expression, that he was at once acknowledged to have distanced all competitors. His acquaintance was now sought by amateurs and literati; but the chief advantage which accrued to him was the friendship of the Chevalier Marini, a distinguished Italian, who had settled in Paris, and engaged with interest in the cultivation of elegant literature and the arts. His mind was stored with classical erudition, and he delighted to exercise his poetic talent on the then fashionable fables of heathen mythology. Such pursuits were congenial to Poussin’s turn of mind; and by the advice, and with the assistance of Marini, he entered deeply into the study of the Latin and Italian authors. Hence he drew the elements of that knowledge of the customs, manners, and habits of antiquity, by which his works are so eminently distinguished. Marini, soon after, went to Rome, and was anxious that Poussin should accompany him; but this the artist found impossible, from the number of unfinished commissions on his hands. In the ensuing year, however, 1624, his long-cherished wish was accomplished, and he trod the streets of the Eternal City.

Among the innumerable pilgrims who have thronged to that mighty shrine, no one ever, perhaps, approached it with deeper reverence than Poussin, or studied in the school of antiquity with more zeal and success. He commenced his labours with that enthusiasm which the objects around him could not fail to inspire, and comprehended in the round of his studies the different sciences which bore collaterally upon his art. Some of his finest works are among those which he produced at this period; but his talents were not at first appreciated in Rome, and the spectre of penury still haunted his study. His friend Marini had gone to Naples, where he died, and the Cardinal Barberini, to whose favour he had been especially recommended, was absent on a legation in Spain. Among other works which his necessities compelled him to dispose of at this time for a trifling sum, was “The Ark of God in the hands of the Philistines,” which was purchased from him for fifty crowns, and sold shortly afterwards to the Duc de Richelieu for one thousand. Accident and ill health combined with poverty to overcloud the early part of his abode in Rome. The French were then very unpopular, on account of some differences existing between the Court of France and the Holy See. Poussin was assaulted in the streets by some of the Pope’s soldiery, severely wounded by a sabre-cut in the hand, and only escaped more serious injury by the spirit and resolution with which he defended himself. After recovering from this injury, he was again rendered unable to pursue his art by a lingering illness; in the course of which a fellow-countryman, named Jean Dughet, took him to his own home, and treated him with care, which soon restored him to health. Six months afterwards he married the daughter of his host, and subsequently adopted his wife’s brother, Gaspar, who assumed his name, and has shared its honours by his splendid landscapes. With part of his wife’s portion Poussin purchased a house on the Pincian Hill, which is still pointed out as an object of interest to travellers and students.

Читать дальше