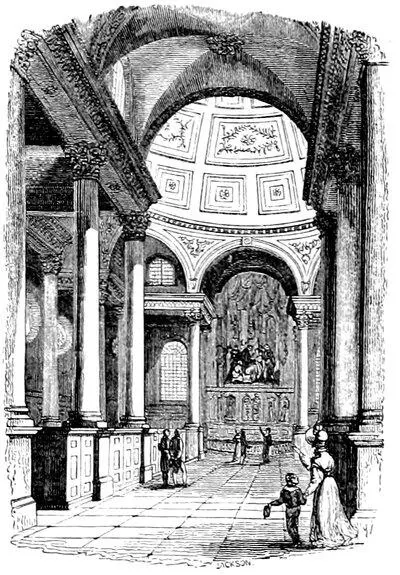

The other architectural works which he designed and executed during this period, both in London and elsewhere, are far too numerous to be mentioned in detail. Among them were the parish church of St. Bride, in Fleet Street, which was finished in 1680, and the beautiful spire of which, originally two hundred and thirty-four feet in height, has been deemed to rival that of St. Mary-le-Bow; the church of St. James, Westminster, finished in 1683, a building in almost all its parts not more remarkable for its beauty than for its scientific construction; and of which the roof especially, both for its strength and elegance, and for its adaptation to the distinct conveyance of sound, has been reckoned a singularly happy triumph of art; and the church of St. Andrew, Holborn, a fine specimen of a commodious and an imposing interior: besides many others of inferior note. In 1696 he commenced the building of the present Hospital at Greenwich, of which he lived to complete the greater part. This is undoubtedly one of the most splendid erections of our great architect. Among his less successful works may be enumerated Chelsea Hospital, begun in 1682, and finished in 1690, a plain, but not an inelegant building; his additions to the Palace of Hampton Court, carried on from 1690 to 1694, which are certainly not in the best taste; and his repairs at Westminster Abbey, of which he was appointed Surveyor-General in 1698. In his attempt to restore and complete this venerable edifice, his ignorance of the principles of the Gothic style, and his want of taste for its peculiar beauties, made him fail perhaps more egregiously than on any other occasion. In 1679 he completed the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge, one of the most magnificent of his works; and in 1683, the Chapel of Queen’s College, and the Ashmolean Museum, at Oxford. The same year he began the erection of the extensive pile of Winchester Castle, originally intended for a royal palace, but now used as a military barrack. To these works are to be added a long list of halls for the city companies, and other public buildings, as well as a considerable number of private edifices. Among the latter was Marlborough House, Pall-Mall. Indeed scarcely a building of importance was undertaken during this long period which he was not called upon to design or superintend. The activity both of mind and body must have been extraordinary, which enabled him to accomplish what he did, not to speak of the ready and fertile ingenuity, and the inexhaustible sources of invention and science he must have possessed, to meet the incessant demands that were made for new and varying displays of his contriving skill. It appears, too, in addition to all this, that the duties imposed upon him by his place of Surveyor of Public Works, for which he only received a salary of £100 a year, were of an extremely harassing description, and must have consumed a great deal of his time. Claims and disputes as to rights of property, and petitions or complaints in regard to the infringement of the building regulations in every part of the metropolis and its vicinity, seem to have been constantly submitted to his examination and adjudication; and Mr. Elmes has printed many of his reports upon these cases from the original manuscripts, which afford striking evidence both of the promptitude with which he gave his attention to the numerous calls thus made upon him, and of the large expenditure of time and labour they must have cost him.

The long series of years during which Wren was occupied in the accomplishment of his greatest work, and which had conducted him from the middle stage of life to old age, brought to him also of course various other changes. He had been twice married, and had become the father of two sons and a daughter, of whom the eldest, Christopher, was the author of Parentalia, or Memoirs of the Family of the Wrens. In 1680, he was elected to the Presidency of the Royal Society, on its being declined by Mr. Boyle; and this honourable office he held for two years; during which, notwithstanding all his other occupations, we find him occupying the chair in person at almost every meeting, and still continuing to take his usual prominent part in the scientific discussions of the evening. In 1684 there was added to his other appointments that of Comptroller of the Works at Windsor. In May, 1685, he entered parliament as one of the members for Plympton; and he also sat for Windsor both in the convention which met after the revolution, and in the first parliament of William III. He afterwards sat for Weymouth in the parliament which met in February, 1700, and which was dissolved in November of the year following.

The evening of Wren’s life was marked by neglect and ingratitude. In the eighty-sixth year of his age he was removed from the office of Surveyor-General, which he had held for forty-nine years, in favour of one Benson, whose incapacity and dishonesty soon led to his disgrace and dismissal. Fortunately Wren’s temper was too happy and placid to be affected by the loss of court favour, and he retired to his home at Hampton Court, where he spent the last five years of his life chiefly in the study of the Scriptures, and the revision of his philosophical works. He died February 25, 1723, in the ninety-first year of his age.

More minute accounts of his life are to be found in the Parentalia, already mentioned, and in Mr. Elmes’s quarto volume. We may also refer the reader to a longer memoir in the Library of Useful Knowledge.

3. In the Life of Boyle this event is stated to have occurred in 1663. A second charter was granted to the Society, in that year, on the 22d of April.

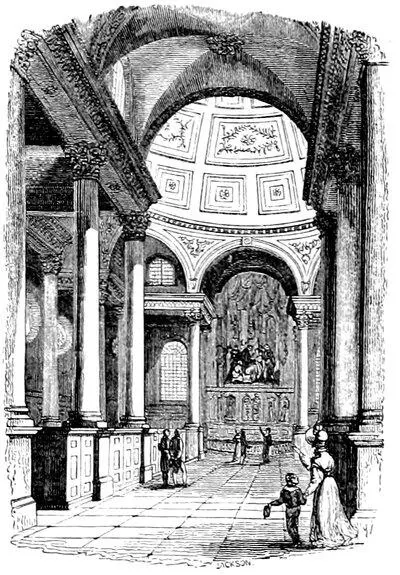

Interior of St. Stephen’s, Walbrook.

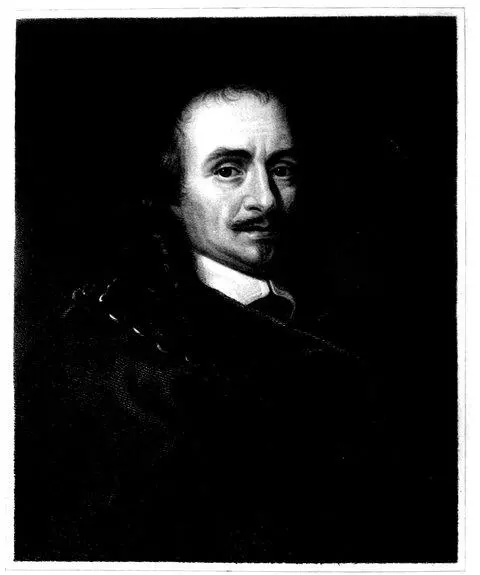

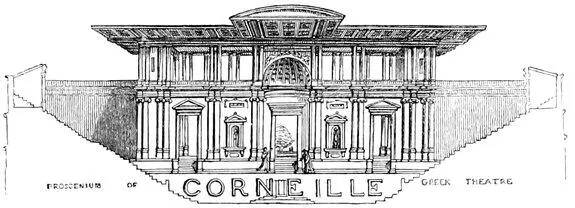

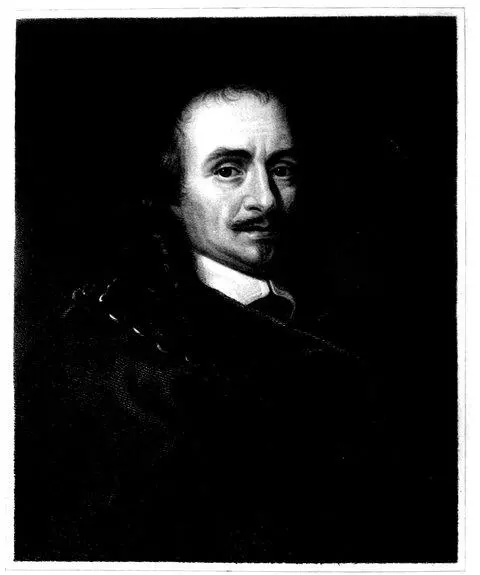

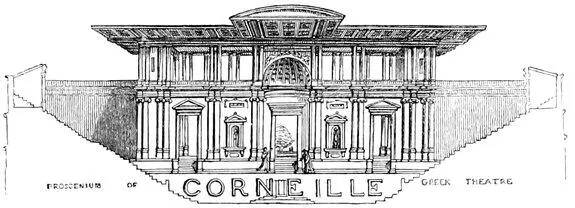

Engraved by T. Woolnoth. CORNEILLE. From an original Picture by C. Lebrun in the possession of the Institute of France. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Peter Corneille was born at Rouen, on the 6th of June, 1606. His father was in the profession of the law, and held an office of trust under Louis XIII. Young Corneille was educated in the Jesuits’ College at Rouen; and, while there, formed an attachment to that society, which he maintained unimpaired in after-life. He was destined for the bar, at which he practised for a short time, but had no turn for business; and with better warrant than the many, who mistake a lazy and vagabond inclination for genius and the muse, he quitted the path of ambition and preferment for a road to fame, shorter, and therefore better suited to an aspiring, but impatient mind. A French writer congratulates his country, that he who would have made an obscure and ill-qualified provincial barrister, became, by change of place and pursuits, the glory and ornament of a great empire in its most splendid day. Corneille “left his calling for an idle trade,” without having bespoken the favour of the public by any minor specimens of poetical talent. He seems indeed to have hung loose upon society, till a petty affair of gallantry discovered the mine of his natural genius, though not in his purest and richest vein. The story is told by Fontenelle, and has been related of many others with nearly the same incidents; being the common-place of youthful adventure. One of Corneille’s friends had introduced him to his intended wife; and the lady, without any imputation of treachery on the part of the supplanter, took such a fancy to him, as induced her to play the jilt towards his introducer. Corneille moulded the embarrassment into a comedy entitled Melite. The drama had hitherto been at a low ebb among the French. Their tragedy was flat and languid: to comedy, properly so called, they had no pretensions. The theatre therefore had hitherto been little attended by persons of condition. Racine describes the French stage when Corneille began to write, as absolutely without order or regularity, taste or knowledge, as to what constituted the real merits of the drama. The writers, he says, were as ignorant as the spectators. Their subjects were extravagant and improbable; neither manners nor characters were delineated. The diction was still more faulty than the action; the wit was confined to the lowest puns. In short, all the rules of art, even those of decency and propriety, were violated. This description gives us the history of the infant drama in all ages and countries; of Thespis in his cart, and of Gammer Gurton’s needle.

Читать дальше