We cannot better close this account, than with a short extract from the sketch of his character, to which we have alluded in a former page. After speaking of the lasting celebrity which Watt has acquired by his mechanical inventions, the author continues, that “to those to whom he more immediately belonged, who lived in his society and enjoyed his conversation, this is not, perhaps, the character in which he will be most frequently recalled—most deeply lamented—or even most highly admired. Independently of his great attainments in mechanics, Mr. Watt was an extraordinary and in many respects a wonderful man. Perhaps no individual in his age possessed so much and such varied and exact information, had read so much, or remembered what he had read so accurately and well. He had infinite quickness of apprehension, a prodigious memory, and a certain rectifying and methodising power of understanding, which extracted something precious out of all that was presented to it. His stores of miscellaneous knowledge were immense, and yet less astonishing than the command he had at all times over them. It seemed as if every subject that was casually started in conversation with him, had been that which he had been last occupied in studying and exhausting; such was the copiousness, the precision, and the admirable clearness of the information which he poured out upon it without effort or hesitation. Nor was this promptitude and compass of knowledge confined, in any degree, to the studies connected with his ordinary pursuits. That he should have been minutely and extensively skilled in chemistry and the arts, and in most of the branches of physical science, might, perhaps, have been conjectured; but it could not have been inferred from his usual occupations, and probably is not generally known, that he was curiously learned in many branches of antiquity, metaphysics, medicine, and etymology; and perfectly at home in all the details of architecture, music, and law. He was well acquainted, too, with most of the modern languages, and familiar with their most recent literature. Nor was it at all extraordinary to hear the great mechanician and engineer detailing and expounding, for hours together, the metaphysical theories of the German logicians, or criticising the measures or the matter of the German poetry. * * *

“It is needless to say, that with those vast resources, his conversation was at all times rich and instructive in no ordinary degree. But it was, if possible, still more pleasing than wise, and had all the charms of familiarity, with all the substantial treasures of knowledge. No man could be more social in his spirit, less assuming or fastidious in his manners, or more kind and indulgent towards all who approached him. * * * His talk, too, though overflowing with information, had no resemblance to lecturing, or solemn discoursing; but, on the contrary, was full of colloquial spirit and pleasantry. He had a certain quiet and grave humour, which ran through most of his conversation, and a vein of temperate jocularity, which gave infinite zest and effect to the condensed and inexhaustible information which formed its main staple and characteristic. There was a little air of affected testiness, and a tone of pretended rebuke and contradiction, which he used towards his younger friends, that was always felt by them as an endearing mark of his kindness and familiarity, and prized accordingly, far beyond all the solemn compliments that ever proceeded from the lips of authority. His voice was deep and powerful; though he commonly spoke in a low and somewhat monotonous tone, which harmonized admirably with the weight and brevity of his observations, and set off to the greatest advantage the pleasant anecdotes which he delivered with the same grave tone, and the same calm smile playing soberly on his lips. There was nothing of effort, indeed, or of impatience, any more than of pride or levity, in his demeanour; and there was a finer expression of reposing strength, and mild self-possession in his manner, than we ever recollect to have met with in any other person. He had in his character the utmost abhorrence for all sorts of forwardness, parade, and pretension; and indeed never failed to put all such impostors out of countenance, by the manly plainness and honest intrepidity of his language and deportment.

“He was twice married, but has left no issue but one son, long associated with him in his business and studies, and two grandchildren by a daughter who predeceased him. He was fellow of the Royal Societies both of London and Edinburgh, and one of the few Englishmen who were elected members of the National Institute of France. All men of learning and of science were his cordial friends; and such was the influence of his mild character, and perfect fairness and liberality, even upon the pretender to these accomplishments, that he lived to disarm even envy itself, and died, we verily believe, without a single enemy.”

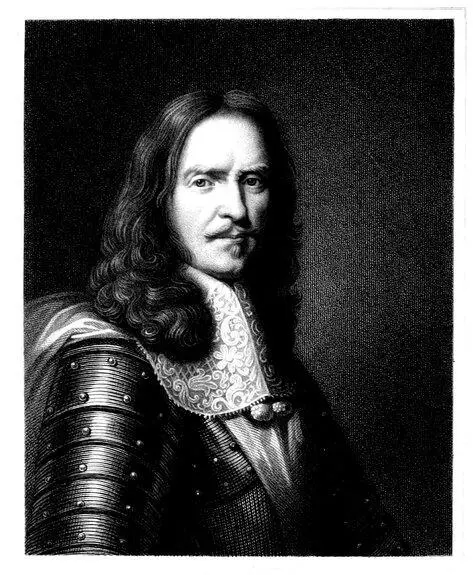

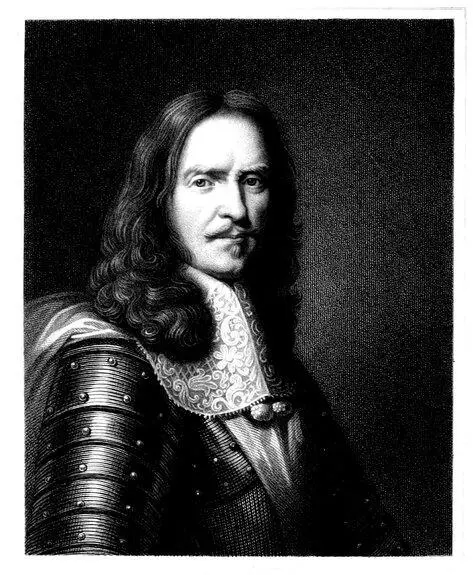

Engraved by W. Holl.

MARSHAL TURENNE.

From the original Picture by Latour, in the collection of the Musée Royale, Paris. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

Table of Contents

Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne, born September 16th, 1611, was the second son of the Duc de Bouillon, prince of Sedan, and of Elizabeth of Nassau, daughter of the celebrated William of Orange, to whose courage and talents the Netherlands mainly owed their deliverance from Spain. Both parents being zealous Calvinists, Turenne was of course brought up in the same faith. Soon after his father’s death, the Duchess sent him, when he was not yet thirteen years old, into the Low Countries, to learn the art of war under his uncle, Maurice of Nassau, who commanded the troops of Holland in the protracted struggle between that country and Spain. Maurice held that there was no royal road to military skill, and placed his young relation in the ranks, as a volunteer, where for some time he served, enduring all hardships to which the common soldiers were exposed. In his second campaign he was promoted to the command of a company, which he retained for four years, distinguished by the admirable discipline of his men, by unceasing attention to the due performance of his own duty, and by his eagerness to witness, and become thoroughly acquainted with, every branch of service. In the year 1630, family circumstances rendered it expedient that he should return to France, where the court received him with distinction, and invested him with the command of a regiment.

Four years elapsed before Turenne had an opportunity of distinguishing himself in the service of his native country. His first laurels were reaped in 1634, at the siege of the strong fortress of La Motte, in Lorraine, where he headed the assault, and, by his skill and bravery, mainly contributed to its success. For this exploit he was raised at the early age of twenty-three to the rank of Marechal de Camp, the second grade of military rank in France. In the following year, the breaking out of war between France and Austria opened a wider field of action. Turenne held a subordinate command in the army, which, under the Cardinal de la Valette, marched into Germany to support the Swedes, commanded by the Duke of Weimar. At first fortune smiled on the allies; but, ere long, scarcity of provisions compelled them to a disastrous retreat over a ruined country, in the face of the enemy. On this occasion the young soldier’s ability and disinterestedness were equally conspicuous. He sold his plate and equipage for the use of the army; threw away his baggage to load the waggons with those stragglers who must otherwise have been abandoned; and marched on foot, while he gave up his own horse to the relief of one who had fallen, exhausted by hunger and fatigue. These are the acts which win the attachment of soldiers, and Turenne was idolized by his.

Читать дальше