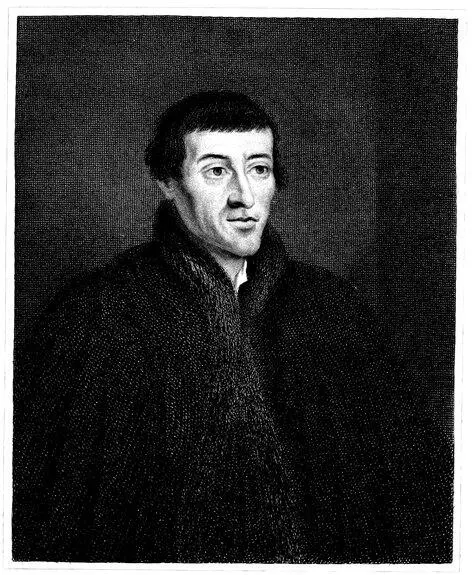

Our Portrait has been engraved from a fine picture by Jackson, in the possession of Lord Dover. There is also an excellent portrait painted by Howard, and a good bust of Flaxman was executed by Baily some few years before our artist’s death.

[“Feed the hungry,” from a bas-relief of Flaxman.]

Table of Contents

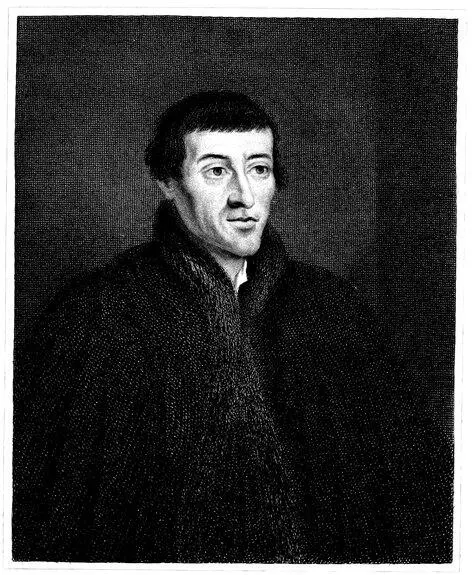

The illustrious discoverer of the true planetary motions, whose features are represented on the accompanying plate, lived during the latter part of the fifteenth century, and the first half of the following one. Notwithstanding the success and celebrity of the theory which still bears his name, the materials are very scanty for personal details regarding his life and character. This ignorance is not the result of recent neglect. A century had scarcely elapsed from the time of his death, when Gassendi, who, at the request of the poet Chapelain, undertook to compile an account of him, was forced to preface it by a similar declaration.

Whilst Europe rang from one end to the other with the fierce dispute to which the new views of the relation and motions of the heavenly bodies gave rise, the character, the situation and manner of life, almost the country, of the great author of the controversy, remained unknown to the greater number of his admirers and opponents. Even the name of the discoverer of the Copernican system now appears strange, except in the Latinised form of Copernicus, in which alone it occurs in his own writings and in those of his commentators.

Nicolas Cöpernik [1], to use his genuine appellation, was a native of Thorn, a city of Polish Prussia, situated on the river Weichsel or Vistula. He was born in the year 1473. Little is known of his parents, except that his father, whose name also was Nicolas, was a surgeon, and, as it is believed, of German extraction. The elder Cöpernik was undoubtedly a stranger at Thorn, where he was naturalized in 1462: he married Barbara, of the noble Polish family of Watzelrode. Luke, one of her brothers, attained the high dignity of Bishop of Ermeland in the year 1489, and the prospects of advancement which this connection held out to young Cöpernik, probably induced his father to destine him to the ecclesiastical profession. He acquired at home the first elements of a liberal education, and afterwards graduated at Cracow, where he remained till he received the diploma of Doctor in Arts and Medicine from that university. He is said to have made considerable proficiency in the latter branch of study; and possessed, even in more advanced life, so high a reputation for skill and knowledge, as to produce an erroneous belief that he had once followed medicine.

Engraved by E. Scriven. NICOLAO COPERNICO. From a Picture in the possession of the Royal Society, presented by D r. Wolf, of Dantzic, June 6, 1770. Under the Superintendance of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. London. Published by Charles Knight, Pall Mall East.

He also exhibited at an early age a very decided taste for mathematical studies, especially for astronomy; and attended the lectures, both public and private, of Albert Brudzewski, then mathematical professor at Cracow. Under his tuition, Copernicus, as we shall hereafter call him, became acquainted with the works of the astronomer, John Müller, (now more commonly known by his assumed appellation of Regiomontanus,) and the reputation of this celebrated man is said to have exercised a marked influence in deciding the bent of his future studies. Müller died at Rome a few years after the birth of Copernicus, and when the latter had reached an age capable of appreciating excellence and nourishing emulation, he found Müller’s works disseminated through every civilized country of Europe, his genius and acquirements the subject of universal admiration, and his premature death still regretted as a public calamity. The feelings to which the contemplation of Müller’s success gave rise, were still more excited by a journey into Italy, which Copernicus undertook about the year 1495. One of his brothers and his maternal uncle were already settled in Rome, which was therefore the point to which his steps eventually tended. He quitted home in his twenty-third year; when his diligence in cultivating the practical part of astronomy had already procured for him some reputation as a skilful observer. It seems to have been in contemplation of this journey that he began to study painting, in which he afterwards became a tolerable proficient.

Bologna was the first place at which he made any stay, being drawn thither by the reputation of the astronomical professor, Dominic Maria Novarra. Copernicus was not more delighted with this able instructor than Novarra with his intelligent pupil. He soon became an assistant and companion of Novarra in his observations, and in this capacity acquired considerable distinction, so that on his departure from Bologna and arrival at Rome, he found that his reputation had preceded him. He was appointed to a professorship in that city, where he continued to teach mathematics for some years with considerable success.

It does not appear at what time Copernicus entered into holy orders: probably it may have been during his residence at Rome; for on his return home he was named to the superintendence of the principal church in his native city Thorn. Not long afterwards his uncle Luke, who, in 1489, succeeded Nicolas von Thungen in the bishopric of Ermeland, enrolled him as one of the canons of his chapter. The cathedral church of the diocese of Ermeland is situated at Frauenburg, a small town built near one of the mouths of the Vistula, on the shore of the lake called Frische Haff, separated only by a narrow strip of land from the Gulf of Dantzig. In this situation, rendered unfavourable to astronomical observations by the frequent marshy exhalations rising from the river and lake, Copernicus took up his future abode, and made it the principal place of his residence during the remainder of his life. Here those astronomical speculations were renewed and perfected, the results of which have for ever consigned to oblivion the subtle contrivances invented by his predecessors to account for the anomalies of their own complicated theories.

But we should form a very erroneous opinion of the life and character of Copernicus, if we considered him, as it is probable that by most he is considered, the quiet inhabitant of a cloister, immersed solely in speculative inquiries. His disposition did not unfit him for taking an active share in the stirring events which were occurring around him, and it was not left entirely to his choice whether he would remain a mere spectator of them.

The chapter of Ermeland, at the time when he became a member of it, was the centre of a violent political struggle, in the decision of which Copernicus himself was called on to act a considerable part. In the latter half of the fifteenth century, a bitter war was carried on between the King of Poland and a military religious fraternity, called the Teutonic or German Knights of St. Mary of Jerusalem, who were incorporated towards the end of the twelfth century. Having been called into Prussia, they established themselves permanently in the country, built Thorn and several other cities, and gradually acquired a considerable share of independent power. On the death of Paul von Segendorf, bishop of Ermeland, Casimir, king of Poland, in pursuance of a design which he was then prosecuting, to get into his own hands the nomination to all the bishoprics in his dominions, appointed his secretary, Stanislas Opporowski, to the vacant see. The chapter of Ermeland proceeded notwithstanding to a separate nomination, and elected Nicolas von Thungen. Opporowski, backed by Casimir, entered Ermeland at the head of a powerful army. From this period the new Bishop of Ermeland necessarily made common cause with the German Knights; they renounced their allegiance to the crown of Poland, and threw themselves on the protection of Matthias king of Hungary. At length, Casimir finding himself unable to master the confederacy, separated Nicolas von Thungen from it, by agreeing to recognise him as Prince-Bishop of Ermeland, on the usual condition of homage. Nicolas thus became confirmed in his dignity, but his unhappy subjects did not fare better on that account, the country being now exposed to the fury of the German Knights, as it had suffered before from the violence of the Polish soldiery. These disturbances were continued during the life of Luke Watzelrode, and the city of Frauenburg, as well as its neighbour Braunsburg, frequently became the theatre of warlike operations.

Читать дальше