After the King’s victorious campaign in Scotland, he was welcomed on his return with a procession and pageant most magnificent. The houses were hung high with scarlet cloth; the trades and crafts appeared, each offering some device or “subtlety” showing its kind of work. Thus, the fishmongers marched with four gilt sturgeons and four silver salmon on horses; they also equipped forty-six knights in full armour, riding horses “made like luces of the sea”; the knights were followed by St. Magnus—his church is at the bottom of Fish Street—with a thousand horsemen.

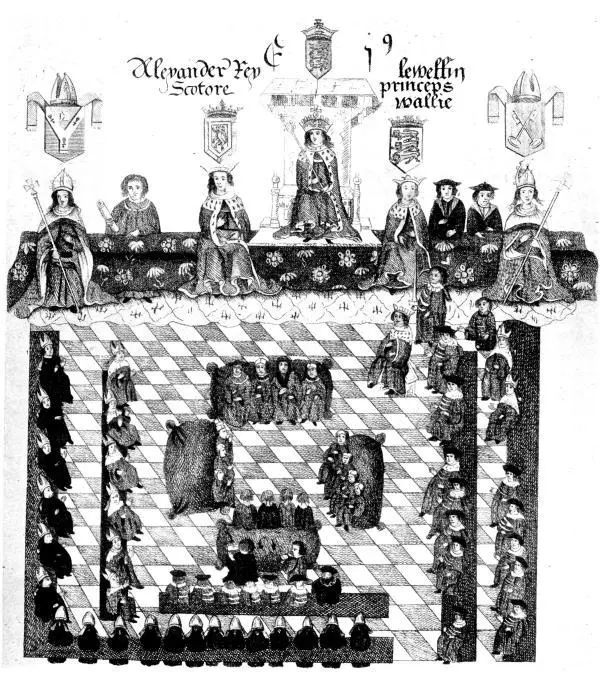

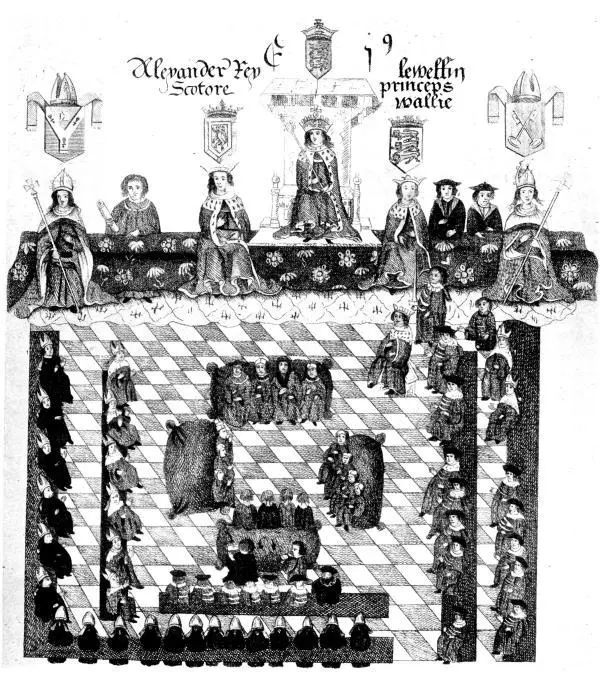

PARLIAMENT OF EDWARD I.

From Pinkerton, Iconographia Scotica.

On August 10, 1305, Westminster witnessed a trial surpassed by few in interest and importance—that of the patriot Sir William Wallace, who had been captured in his Highland retreat by treachery, and had been brought to London. Wallace was at this time not more than thirty years of age: in the full vigour of manhood and of genius. He had filled his short life with fights and forays. As a hero of romance, the ideal patriot, all kinds of legends and stories have accumulated round his name. All we know for certain about him is that he was at the head of an army gathered from that part of the Lowlands lying north of the Tay; that without the help of the Scottish earls or barons he defeated the English at Stirling and drove them out of the country; and though he was defeated at Falkirk he awakened in the hearts of the Scots the spirit of independence: he made them a nation. On his arrival in London the illustrious prisoner was taken to the house of a private citizen, William De Leyre by name, who lived in the parish of Allhallows the Great. It does not appear why he was not taken to the Tower. Perhaps it was desired to attach as little importance as possible in the case. “Great numbers,” however, according to Stow, “both men and women came out to wonder upon him.... On the morrow, being the eve of St. Bartholomew, he was brought on horseback to Westminster, John Segrave and Geoffrey, knights, the Mayor, Sheriffs and Aldermen of London and many others, both on horseback and on foot, accompanying him: and in the Great Hall at Westminster he being placed on the south bench, crowned with lawrel—for that he had said in time past that he ought to bear a crown in that hall as it was commonly reported—and being appeached as a traitor by Sir Peter Mallorie the King’s Justice, he answered that he was never traitor to the King of England: but for other things whereof he was accused”—what were those other things?—“he confessed them.” What he pleaded was, in fact, that he could be no traitor because he owed no allegiance to the King of England. It is clear from this statement that the name and fame of William Wallace were spread over the whole of England; and that the man who had driven out the English and ravaged Northumberland and defied the conqueror, was sent up to London as a captive fore-doomed to death. The prentices ran and shouted; the women looked out of the upper chambers—pity that a man so gallant, who rode as if to his wedding instead of his death, should have to die the death of a traitor. As for the manner of his death, it followed the usual ceremony: first he was dragged at the heels of horses to the place of execution, the Elms at Smithfield; he was placed on a hurdle, otherwise he would have been dead long before reaching the place, for from Westminster Hall to the Elms, Smithfield, is two miles at least. There were multitudes waiting at Smithfield to see this gallant Scot done to death. First they hanged him on a high gallows, but only for the ignominy of it, not to kill him; then they took the rope from his neck, laid him down, took out his bowels and performed other mutilations which one hopes were done when the life was out of him. Then they cut up his body and distributed it in parts: some to rejoice the hearts of the English on London Bridge, at Newcastle, at Berwick: and of the Scots at Perth and Aberdeen. The business was as barbarous as possible, but it was the fashion of the time. Two hundred and fifty years later in the reign of Queen Elizabeth the same punishment in all its details was inflicted upon Babington and his friends. Three hundred and eighty years later almost the same punishment was inflicted upon Monmouth’s adherents. The execution itself, apart from the cruel manner of it, which belonged to the time, is generally condemned as a blot upon the life and reign of the great Edward. Perhaps, however, the history of the case may show some reason for an act quite contrary in spirit to the King’s usual treatment of the indomitable Scots. After the overtures of Balliol, the Scottish lords swore homage to Edward. Wallace alone—a simple knight—refused to recognise the surrender, called the people to arms, against the wish of nobles and priests, drove the English out of Scotland and led a foray into Northumberland. At the battle of Falkirk the Scots were defeated and cut to pieces, Wallace himself escaping with difficulty. That was in 1298. But the struggle was continued. For six years Edward was occupied with other troubles. When, in 1304, he again invaded the country, the Scottish lords laid down their arms and the conquest of Scotland was accomplished without further bloodshed. A general amnesty was extended to all. But the name of Wallace was excluded—“let him submit to the grace of the King, if so it seemeth him good.” Wallace would not submit: he retreated to the Highlands, where he was captured.

GREAT SEAL OF EDWARD I.

In every age civilised war is governed by certain rules: one must play the game according to these rules. One of them is that when the King has accepted peace, there shall be peace. Wallace might be supposed to have broken that rule. His country had submitted formally: he alone stood out. Patriot he was, no doubt. So was Andreas Hofer; but irregular warfare everywhere is treated as treason or rebellion. And therefore the King, who might well have shown a magnanimous clemency, was justified in his own eyes in putting Sir William Wallace to a shameful end.

The opinion of the English people upon Wallace may be understood from that of Matthew of Westminster, who pours a shower of abuse upon his head. William Wallace is “an outcast from pity, a robber, a sacrilegious man, an incendiary, a homicide, a man more cruel than the cruelty of Herod, more insane than the fury of Nero.” He made men and women in the North of England dance naked before him; he murdered infants; burnt boys in schools “in great numbers,” and at last ran away and deserted his people.

It remains to be added that Wallace’s head was the first of many which decorated London Bridge.

The remarkable robbery of the King’s Treasury by Podelicote took place in 1305.

In the same year the King offered an excellent example of obedience to the laws by sending his son, Prince Edward, to prison for riotously breaking into the park of Walter Langton, Bishop of Chester, and at the same time banished from the realm the Prince’s companion and unworthy friend, Piers Gaveston.

On July 7, 1307, King Edward died while on his way to carry out his vow of vengeance against Bruce.

Table of Contents

The least worthy, or the most worthless, of all the English sovereigns, was the first who sat upon the sacred stone of Scone, brought into England by Edward I. The coronation was held on February 25, 1308, the Queen being crowned with the King. The Mayor and Aldermen took part in the function and in the banquet afterwards.

Читать дальше