Otto’s patent included a system for stratification of the explosive charge which proved to be useless, but the four-stroke cycle remained and earned him and his firm a fortune in royalties until 1882.

Brayton’s engine inspired George Selden, a clever patent attorney who became convinced that the Brayton-powered automobile was at hand. By deferring the definitive grant of his patent until the 1890s he obtained a master patent on the automobile that would also earn him a small fortune.

The year 1876 can be considered as the year of the great master patents. Pénaud’s aeroplane, Otto’s four-stroke cycle and Selden’s automobile. Selden’s deferments were eventually stymied because Brayton came too late with his new two-stroke system with the result that Selden was too early with his patent, which did not include the four-stroke cycle, leading to him being eventually defeated on that account. But one cannot anticipate everything.

Pénaud’s Tragic End

The story of Pénaud’s subsequent efforts on behalf of dynamic flight is a sad one. He became increasingly detached from his colleagues in the Société de Navigation Aérienne and in 1876 resigned from his position as archivist and from the committee, resigning altogether in 1879. His successes with his flying models, his talents and his force of mind had evoked jealousy rather than admiration, a not uncommon occurrence in the history of mankind. He became bitter, quarrelled with his family and his health became further impaired.

Pénaud was left with only the hope of bringing his aeroplane project to fruition. For that he needed help and money but instead he found himself sliding into the situation similar to the one that he had perceptively ascribed to Sir George Cayley. He, too, was not understood, and was neither encouraged nor helped although fortunately his inspirational ideas were not forgotten entirely.

He thought he had found a man who could help him and began to keep company with Henry Giffard, who in 1852 had been the first person to design and fly a steam-powered dirigible airship. In the course of his experiments Giffard had developed and patented a water-injector for steam generators. His injector was a success and enabled him to amass a fortune. Here was just the man, thought Pénaud, someone rich and aeronautically minded who would be able to assist him with his projects.

But Giffard had become a lonely, ill misanthrope, and moreover, the times appeared to favour the airship for which Giffard had more sympathy and which had made him famous. Pénaud, in desperation, became more and more insistent, with the inevitable result that Giffard closed his door to him.

This, to Pénaud, was the end. He put all his aeroplane projects and manuscripts into a little coffer in the form of a casket, added a note that eight days later he would be dead and delivered the funereal package at Giffard’s home.

There was no reaction from Giffard and eight days later, on 22 October 1880, Pénaud shot himself in a fit of acute depression. This tragedy triggered another, because Giffard, possibly feeling himself partly responsible for Pénaud’s death, withdrew even further from the outside world, eventually committing suicide by inhaling chloroform.

Victor Tatin takes over

Before he left this world, Pénaud had at least attracted an admirer and fervent disciple in the person of Victor Tatin, a talented young jeweller who had started his aeronautical activities by joining the confraternity of flapping-wing experimenters.

His first product was a little jewel of a bird, as befitted his trade. It weighed only 5.15 grams and was ready in mid-1874, but at its first public showing, during a lecture by Pénaud, it broke before it could fly.

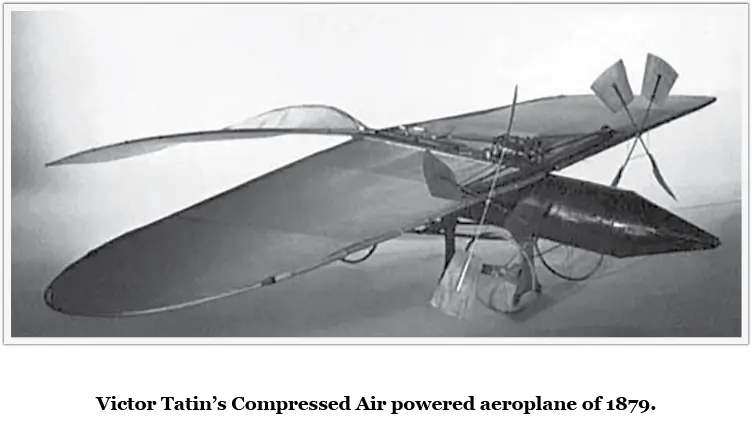

He persisted along these lines for another three years, making bigger and bigger birds until he realized that flapping-wing flight would take him nowhere and he bowed to the evidence. He went over completely to Pénaud’s ideas of fixed-wing machines and in 1878 and 1879 built a model monoplane, aided by the intervention of Professor Marey, who found a backer willing to invest 1,500 francs to support this aviation initiative.

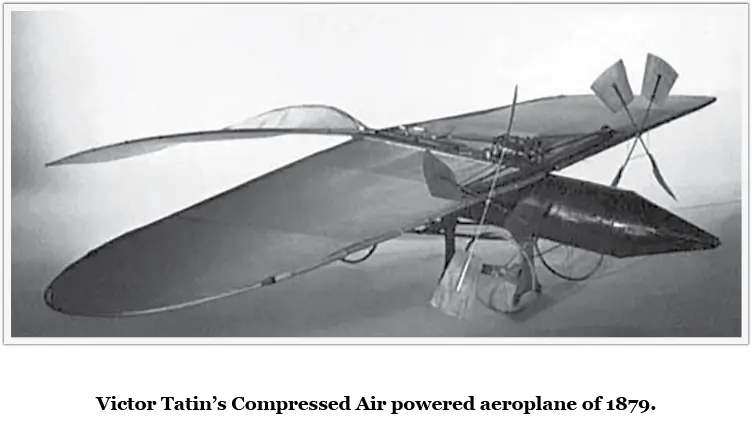

This was the first fixed-wing aeroplane built after Pénaud’s little planophores and it was a much more ambitious undertaking. Its total weight was 3.85 lbs and with wings of 8 sq ft, the wing loading was 0.48 lb/sq ft, still fairly low. It was powered by a piston engine driven by compressed air and two contra-rotating propellers were placed in front of the wing.

Tethered to a pole in the park of the official aeronautical establishment of Chalais-Meudon, it could progress only around a circular track. When the motor was started the machine accelerated rapidly and when it reached a speed of 8 m/s (18 mph) the plane rose. But the results were not sufficient to induce the backer to invest more money.

Much time was then lost in finding another backer. One eventually materialized in the person of Charles Richet, who advanced 20,000 francs. This allowed Tatin to build a bigger model, powered by steam and weighing 33 kg (73 lbs). The wings covered 8 sq m (86 sq ft) so that the wing loading rose to 0.85 lb/sq ft and take-off speed rose appreciably. But the steam engine developed around 1 hp, and this appeared to be sufficient.

The propellers worked in tandem, one at the front and one at the rear of the body. They ran in opposite directions so as to avoid any upsetting torque.

The decision was taken to test the aeroplane over water, and the first experiment was undertaken in 1890 at Sainte Adresse on the Mediterranean coast. The plane started from a ramp before continuing on a horizontal path until flying speed was achieved. At 18 m/s (40 mph) the plane duly rose, but after a flight of about 60 m (300 ft) a construction defect caused it to crash on the rocks beneath the cliffs that formed the coastline.

The plane was completely destroyed, but after much time and trouble it was eventually rebuilt. A second test was undertaken in 1896 at Carqueiranne, also on the coast, the engine giving about 25% more power.

This time the Pénaud tail was not adjusted properly and after a flight of about 220 ft., it started to climb, stalled and fell into the sea. It was recovered and repaired and a third test was held in June 1897, but again, after a flight of 440 ft., the plane stalled due to a defect in balance and the succeeding crash ended the experiments.

Meanwhile, Professor Langley had obtained better results in the United States and Richet decided to halt further work. Had Tatin been able to continue he would no doubt have succeeded in adjusting his plane for satisfactory flights, but it was not to be.

When the experiments with full-size machines began, some ten years later, Tatin was around with advice and counsel, he wrote numerous articles and was probably instrumental in convincing several pioneers not to ignore Pénaud’s teachings at a time when another mode of flying had become preponderant.

The evolution towards a practical aeroplane, which was started by Cayley and continued by Pénaud, was leading towards a stable and controllable flying machine that would be able to carry heavy loads over great distances at high speeds. In 1880, at the time of Pénaud’s death, it appeared that most of the problems had been solved and that the only impediment towards the final take-off was the powerplant, which was also felt to be within reach.

Читать дальше