1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...27 D’Esterno never built his machine and we do not know how many would-be birdmen were inspired by him, but we do know that one soaring machine was actually built around 1867 by Joseph Le Bris, a sailor and sea-captain who was inspired by the albatross. The records show that Le Bris really designed a flapping-wing model in 1857 and later a helicopter project but they were both unsuccessful. It seems likely that Le Bris was inspired by d’Esterno’s pamphlet to build a machine like the one d’Esterno had proposed in 1864. The similarity lay in the fact that curved wings of an identical 215 sq ft surface were used and that the tail could affect movements like those in d’Esterno’s project. According to his biographer, Le Bris was able to effect all the complicated steering movements by standing upright, his hands on the different levers and cords that moved the wings and his feet on a pedal that worked the tail.

It has been stated that Le Bris really did fly his contraption and that he was able to soar upwards after taking off from a cart when the horse had been urged to full speed. The story further relates that Le Bris was just preparing for an extended soaring flight when he became aware of cries of anguish from below and saw that the driver of the cart had become entangled in the rope. The driver was also flying, even if much against his will. This doubling of useful load did not apparently affect the flying characteristics of Le Bris’ untried and unpowered soaring machine, which is enough to arouse our admiration. But when the tale continues by stating that Le Bris was able to deposit the unlucky cart-driver gently on earth, and afterwards to land unhurt himself, our admiration turns into amazement and, by using a normal amount of critical judgement, ends in disbelief because all this sounds fanciful in the extreme.

When we then learn that nobody in 1867 (let alone in 1856 as has been stated) ever mentioned Le Bris’ flight and that it was made known for the first time in 1878 by de La Landelle as a part of a novel with the striking but unaeronautical title of Les Grandes Amours , we are inexorably led to the conclusion that Le Bris’ flight of 1867 was a figment of the novelist’s imagination.3

A photograph taken in 1867 of Le Bris’ soaring glider (complete with cart) was exhibited by de La Landelle in July 1883 at the Aeronautical Exhibition of the Trocadéro in Paris. It was one of the big attractions at this Exhibition and has since been published several times in many aviation history books. One interesting consequence was that d’Esterno, who was by then an old man, was urged during that year to use some of his money to build the craft he had designed in 1864. He seems to have accepted the challenge, and arrangements were made with Claude Jobert, a mechanic who had built a rubber-band powered ornithopter prototype in 1871, and had himself proposed a model for an experimental construction along these lines in 1882, but d’Esterno died soon afterwards and the matter was dropped.

3. In a later book, de La Landelle explained that he had received the information from Le Bris’s neighbours, which does not make the story more credible.

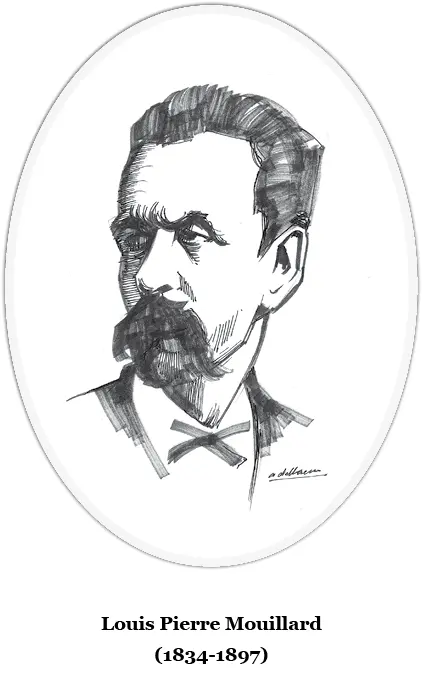

L. P. Mouillard

A few months after Pénaud had sent his resignation to the Société Française de Navigation Aérienne , they received a letter from Louis Pierre Mouillard who explained that in the flight of a flapping bird its tail was of no use. This was a rather unusual statement and Mouillard ended his letter by stating: “If I were rich, I would like to solve the aerial problem in three years.”

Mouillard had become a fanatical devotee of soaring flight as achieved by the big birds of prey, which he had studied first in Algeria and later in Egypt, where he worked in Cairo. During his stay in these subtropical countries he had assigned himself the formidable task of analysing, measuring and describing all the birds he could lay his hands on and had finally come to the same conclusion as d’Esterno, that man would be able to fly with the power of the wind.

In 1881, Mouillard published a remarkable book with the suggestive title of L’Empire de l’air , that caused quite a stir because his belief in the possibility of soaring flight was strongly expressed: “Ascension is the result of the skilful use of the power of the wind and no other force is required.”

Hureau de Villeneuve wrote a long appraisal of Mouillard’s book in the October 1881 issue of L’Aéronaute , analysing the concept of soaring flight which had baffled so many researchers. In his review he rejected Pénaud’s theories that explained soaring flight by “so-called” rising currents which Pénaud “supposed” to exist in the atmosphere.

Like Mouillard, Hureau de Villeneuve found Pénaud’s interpretation unacceptable and he gave two reasons for his inability to agree with Pénaud. The first was that, if these thermals existed, all objects — not only birds — would go up, and the second was that if these rising currents really existed, birds would presumably be able to soar but would not be able to come down again when they wanted to.

Continuing his analysis of Mouillard’s book, Hureau de Villeneuve stated that a soaring bird was nothing but a kite in which the line was replaced by a “continuous displacement of the centre of gravity” which was the result of “a great instinctive skill on the part of those birds”.

These premises were nonsensical and, coming as they did from the president of the French aeronautical society, they may give us an inkling of why Pénaud at times had great difficulty in keeping an even temper when discussing aeronautics with his colleagues at the society meetings.

It is difficult to assess the real importance of Mouillard’s ideas. His book was very well received on publication, and he certainly inspired several pioneers who worked during the last decade of the nineteenth century. His influence extended to the United States just at the crucial moment when human flight was nearing its realization.

But in the light of our present knowledge, his influence, oriented as it was in opposition to Pénaud’s theories, can hardly be termed to have been positive.

Further Progress on the Powerplant

Whilst a new school of pioneers were beginning to dream of flight without power, the aircraft engine was progressing with giant strides.

The German engineer Nikolaus Otto’s success in making a smooth-running four-stroke engine has been discussed above. The Otto engine was much too heavy to serve on aircraft, which needed a powerplant along the lines of Ponton d’Amécourt memorable words of 1864: “What is needed for the conquest of the air is a horse in a watch-case”.

Jules Armengaud, an eminent engineer of that time, discussing the new Otto engine in the January 1878 issue of L’Aéronaute arrived at the conclusion that in order to become light, gas engines would have to reach a high rate of revolutions. It was a perfectly logical conclusion and the way towards the high-speed engine was opened shortly afterwards by Gottlieb Daimler, a manager of the Deutz Company.

Daimler was a fiery character continually at loggerheads with his colleague Nikolaus Otto and for that reason he had seen his contract with Deutz repealed in June 1882.

Daimler lost no time in persuading another first class engineer, Wilhelm Maybach, to leave Deutz as well, and together they worked out a way to create a small high-speed four-stroke engine and actually had one running at 600 rpm by the end of 1883.

Читать дальше