The wagons and guns were, however, a serious embarrassment, and while at Monclova Wool satisfied himself that he could not march from there to Chihuahua by the direct route. A lack of water also was a grave difficulty. Besides, a large force appeared under the present circumstances unnecessary. Ampudia retreated to San Luis Potosí; and although Santa Anna had taken steps, before the American expedition left the Rio Grande, to prepare for the defence of Chihuahua, the military forces holding that point had fallen back on Durango. There was indeed nothing for Wool to conquer now but distance, and he felt that five or six hundred men could do this as well as more. In his opinion, therefore, the proper course was to proceed about 180 miles in a southwesterly direction to Parras, where he would be on a good road to Chihuahua and only about 90 miles from Saltillo; and indeed he thought it advisable to join the main army. His views were duly expressed to his superior officer, and Taylor concurred. The government, concluding that the revival of the federal system at Mexico would change the sentiment of the northern states, and that Chihuahua was in effect already in our grasp, took a similar position;22 and accordingly on the twenty-fourth of November, leaving four companies to guard the stores at Monclova, Wool set out for Parras.26

The long march, generally through deserts and rugged mountains, was cheered by a halt at a fine estate belonging to gentlemen who had received their education in Kentucky, and still cherished the most cordial recollections of their American experiences; and on December 5 the army pitched its gray tents in front of the town. By many Parras, a place of about the same size as Monclova, was called an Eden. It lay where a wide plain and a long hill met, and most of the streets were extremely narrow and crooked; but streams of clean water flowed through them, and most of the residences were buried in gardens or vineyards. But even amidst the luxury of romantic nature firm discipline continued. The soldiers were kept at their drills and parades; their arms and clothing had to be ready at all times for a close inspection; as at Monclova, a system of calls and signals made surprises impossible; and Wool busied himself in procuring corn and flour and in reconnoitring.26

All the while he looked for orders, and finally the summons came. December 17, at a little before two o’clock in the afternoon, he rode hastily into town with staff and escort, holding despatches in his hand; and at once the aides and men hurried through the markets crying out, “Soldiers, to the camp instantly!” As will appear in due time,23 the call was urgent. But it found Wool ready as usual, and in two hours his army—leaving the sick under guard and taking with it 350 wagons, provisions for 60 days, 400,000 cartridges and 200 rounds for the cannon—set out. No blundering occurred. Thanks to his reconnaissances Wool knew which of the routes to pursue. And there was no loitering. Once the troops made thirty-five miles in twenty-four hours; and in four days they shook hands with General Worth’s brave men, then some twenty miles beyond Saltillo and 110 or perhaps 120 from Parras.26

“An entire failure,” was Taylor’s comment on Wool’s expedition, and in a sense his judgment appeared to be correct.24 But this was Polk’s fault. Where there is nothing to do, nothing can be done.25 Before laying out the campaign the government should have seen what it had now seen—that Saltillo was the key of Chihuahua, and that a properly equipped expedition could not reach the latter city without passing rather close to the former. But in reality Wool accomplished a great deal. He showed how a real soldier, without fear and without political yearnings, could lead an expedition through an enemy’s country. Nine hundred miles this army marched. Swift rivers were quickly crossed, ravines filled, hills cut down, mountains climbed. Provisions never failed. No wreckage marked the route. Not a drop of blood was shed; not a shot fired. Wool made enemies only among those who were under obligations to be friends, and made friends among those who were under obligations to be enemies. And out of a crude, heterogeneous mass he forged a keen, tough, highly tempered blade, that was to prove its value soon in a terrible crisis.26

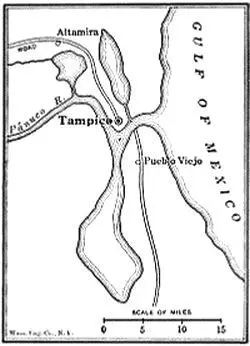

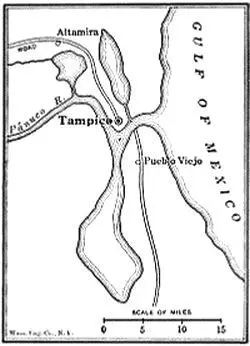

The other lateral expedition moved against the city of Tampico. This place, the principal town in the state of Tamaulipas, and after Vera Cruz the chief port of Mexico on the Gulf coast, was physically remarkable. Land and water are perhaps nowhere more freakishly intermingled. But for practical purposes one may describe it adequately as on a low ridge—with the immense lagoon of Carpintero on the one hand and the deep, wide, heavy, greenish-brown Pánuco on the other—a little more than five miles from the Gulf, as the river flows. For ten years beginning in 1835 political upheavals and vexatious commercial regulations had militated against its prosperity; but the port was highly prized by the government, and in April, 1846, was taken into its particular care.38

All the old fortifications having been demolished lest they should be turned to account by insurgents, Parrodi, the comandante general, was ordered to prepare the town for defence, and a number of badly planned and badly constructed works—particularly a redoubt equipped with two 8-pounders on the north side of the Pánuco at the bar—gave a semblance of security. Some twenty-five light or fortress guns were placed; but efforts to obtain additional heavy ordnance from Vera Cruz were frustrated by the blockade, and when Ampudia, going north in the summer, was directed to give his first attention to reinforcing the garrison, circumstances again intervened. The people were spirited, however; and the daily Eco voiced their sentiments by exclaiming, “With such officers, with such troops, with such citizens let the Yankees come whenever they please!”38

As a matter of fact the Yankees had thoughts of coming quite soon. Possession of the town seemed to be desirable, in the first place, because for some time it was supposed to be the starting-point of a carriage-road to San Luis Potosí, and apparently could be made a more convenient base than the Rio Grande for a deep advance into Mexico; but the war department found before long that wagons and artillery could not cross the mountains by that route. In the second place occupation of Tampico appeared to be a logical feature of the Tamaulipas movement, in which Patterson was expected to play a leading rôle;27 and moreover, Santa Anna himself had explained to Mackenzie that it would be advantageous as well as easy to make this conquest.38

Conner had his eye upon the place, of course; but, aside from the question of overcoming its defenders, he felt considerable hesitation. It was regarded as the most dangerous port on the coast, and vessels could not ride out a gale at anchor off the shore. The bar, on which eight feet of water stood normally, had only a fathom in August, 1846; and as the fleet would have to rendezvous and prepare for battle in the open roadstead, he was afraid that one of the frequent northers would assail him before he could assail the town. September 22, however, when deciding upon the Tamaulipas expedition, Polk and his Cabinet agreed that Conner should attack Tampico, and the order was issued that day.38

Santa Anna seems to have remembered the advice given to Mackenzie, and while at Mexico he instructed Parrodi to retire, if attacked, unless he could be sure of resisting successfully. On his way to San Luis he evidently received Marcy’s intercepted letter of September 2, which announced that a movement upon Tampico was contemplated.28 Hence on October 3, with a view to the confirmation of those instructions, he directed the war office to notify Parrodi of the American plan. Two days later the comandante general reported to Santa Anna that he could not defend the town victoriously, and explained in detail why. His garrison, including some 200 sick, consisted of less than 1200 men besides 200 available National Guards, ignorant of the use of arms. Only 870 of these men could be employed, according to a later statement of his, at the town and the bar, and having but 150 regular gunners he could not man the numerous and widely separated positions. Indeed he would not be able to subsist the garrison more than eleven days longer.29 The enemy, on the other hand, it was said, included a shore party of 3000, and could attack by water and by land at the same time.38

Читать дальше