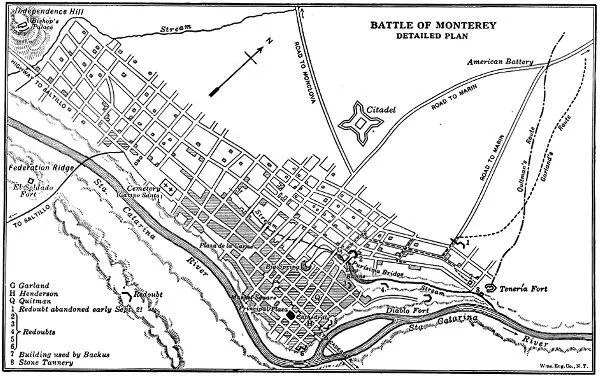

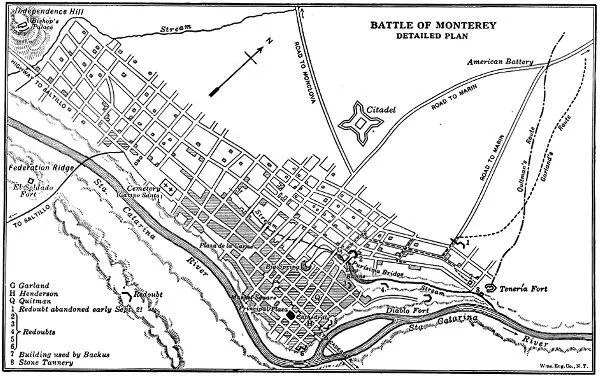

Evidently, however, this meant a severe struggle. Going three quarters of a mile west from the main plaza of Monterey by the Saltillo route, passing a cemetery, and keeping on about a mile and a quarter farther, one found on a low eminence at the right a dilapidated but massive stone building known as the Bishop’s Palace, close below which stood now a half-moon battery facing and commanding the town. Beyond this redoubt, called La Libertad, the eminence became an ascending ridge, and some three hundred yards from the Palace the ridge ended sharply as the summit of an extremely steep height known by the Americans as Independence Hill (Loma de Independencia), where a small sand-bag redoubt had been constructed. Immediately west of this hill, what was known as the Topo road left the Saltillo highway and struck off toward one’s right, and near the farther edge of this road a spur of the mountain began to ascend. On the other side of the highway flowed the Santa Catarina, passing by the city and joining the San Juan some distance below. Farther to the left and parallel to the river rose a high, bristling hill named Federation Ridge. At the western end—the summit—of this ridge, which extended some distance beyond La Libertad, stood a redoubt occupied by some eighty men; and about six hundred yards to the east, in a depression of the ridge, was a substantial masonry fort called El Soldado, armed with two 9-pounders, which were dragged, before the fighting began, to the redoubt on the summit.2

Meantime the Mexicans also were observing. It was generally believed that Taylor had thirty guns, which meant a hard fight; but the soldiers were excited and ready for battle. “The enthusiasm is great, the determination greater, the desire to sacrifice ourselves for the sacred rights of the nation unbounded,” wrote the comandante general of Nuevo León. But Ampudia—“the Culinary Knight,” as Worth called him, who had fried Sentmanat’s head—already trembled. We have food for barely twenty days, he reported to the government; the troops at San Luis Potosí are few in number and little inclined to advance; through spies the enemy are aware of these facts; they will gain the pass between here and Saltillo, and from that position “it will be almost impossible to dislodge them.”3

Sunday morning all was bustle in the American camp, and at length, a little before two o’clock, Hays and about 400 mounted Texans rode away. A long sky-blue line of infantry followed them, and then another line of men in dark-blue jackets and trousers with a red stripe down the leg—Lieutenant Colonel Childs’s Artillery Battalion. Blanchard’s Company of Louisiana volunteers, dressed in every sort of clothes and carrying every sort of weapon, and Duncan’s and Mackall’s batteries with their gleaming pieces and clattering caissons completed the detachment, which included some 2000 men, all told. The rest of the army watched their departure with keen interest, for their design looked well-nigh desperate, and yet the fate of the campaign was believed to depend upon it.4

Especially they watched the commander. In the usual undress uniform but on a splendid horse, which he managed with consummate address, rode Worth. He was a man of average height but noticeably strong, with a trim figure and a strikingly martial air. Conversing easily with his staff he seemed the elegant gentleman; but his face was stern, and his restless dark eyes flashed. In war he found his element; and at present behind his natural ardor burned a new flame. His withdrawing from the army in April had injured both his prestige and his relative position, and his motto now was, “A grade or a grave.” His orders were to turn Independence Hill, occupy the Saltillo highway, and so far as practicable carry the works in that quarter; and no doubt he intended to do more rather than less.4

Soon taking leave of the road, this command plunged into cornfields and chaparral. Progress was difficult and slow. For the benefit of the artillery, ditches had to be bridged or filled and brush fences opened. The enemy promptly observed and understood the movement, and a body of cavalry embarrassed it somewhat. Once they nearly surrounded the General and his staff, who were some distance in advance; but after a time, fearing his artillery, they withdrew to the citadel. Ampudia himself rode to Independence Hill, watched the blue line a while, ordered one hundred infantry to the summit, and had a 12-pounder and a howitzer planted there.5

By six o’clock Worth made nearly or quite seven miles. He was now on the Topo road; and, halting just beyond the range of the battery on Independence Hill, he pushed a reconnoitring party toward the Saltillo highway. Infantry and cavalry had now been posted, however, in that vicinity. The party was fired upon; and, owing to this, to nightfall and to the torrents of rain, its purpose was not accomplished until the lateness of the hour prevented further operations. With great difficulty the Americans were placed in a fairly defensible position; and without fires, food, blankets or shelter, they lived through the stormy night as best they could. By this time the rest of the Mexican cavalry had been withdrawn from its position between the Bishop’s Palace and the citadel, and a part of it retired into the town.6

Monday, a day of fate, broke heavy, dark and ominous. Dense clouds covered the sky, and for a time a thick mist cut off the outlook. By about six o’clock Worth moved, however, and, saluted occasionally with harmless grape from Independence Hill, advanced by the Topo road. Anticipating trouble, he arranged the column so as to be ready for prompt action. The Texans led; Captain C. F. Smith and the light companies of the Artillery Battalion, deployed as skirmishers, came next; Lieutenant Colonel Duncan’s battery was third; and the rest of the command followed. Two or three hundred yards or so from the Saltillo highway, at a turn round the mountain, some two hundred lancers could be seen approaching. It was a gallant sight. The horses, though small, showed plenty of spirit; many of the saddles were silver-mounted; the cavaliers wore brilliant uniforms, and green and red pennons fluttered gayly from their poised lances. At the head of the advance rode Lieutenant Colonel Nájera, a tall, fine-looking trooper with a fierce black mustache. Smith’s corps and a part of the Texas riflemen were thrown behind a strong fence; Duncan halted and unlimbered; and then, like a whirlwind, Nájera struck McCulloch.7

The shock was terrible; and like a lion and a tiger grappling the two bodies writhed and fought. The weight of the American horses proved a great advantage, but numbers were on the other side. Nájera, after running a Texan through with his lance, fell; but a gallant successor took his place, and the soldiers proved worthy of him. Many lances were shivered, and others, useless at close quarters, were dropped; but sword and escopeta served instead. On our part Smith’s infantry fired well, and the Mexicans could not break through the fence.7

After recoiling a little they formed to charge again. Other troops of Worth’s came up, took post beside the road, and began work. A minute or two more and Duncan, on higher ground, was firing over the Americans. By this time Nájera’s squadron was nearly accounted for; but behind it were the rest of Romero’s cavalry brigade and a party of infantry. However, Mackall’s battery was now coöperating with Duncan’s and both did splendidly. The Mexican foot withdrew instead of advancing. A part of the cavalry soon retreated toward Saltillo and a part into the town; and the brief but important struggle ended. Probably more than one hundred Mexicans had been killed or wounded, while our own casualties appear to have numbered about a dozen, and the way to the Saltillo highway lay open. By a quarter past eight Worth’s command was on this road; and he reflected with exultation that the Mexican line of communication, supply, reinforcement and retreat had been cut. Nor was that all or even the best of it, he believed. “The town is ours,” he scrawled in pencil to the commander-in-chief. The battery on Independence Hill now became active, however; and as Federation redoubt, of which the Americans had not heard, began to drop round shot among our troops, they had to be withdrawn about half a mile in the direction of Saltillo.7

Читать дальше