“Woe to the mullein-stalk that came in our way.”

Persons of a mature age, who had bulked large at home, would not stoop to plod through the rudiments of a new profession. Even good officers were in fear of the letters written by their men and the revenge that might be taken later, should real discipline be enforced; while those less conscientious threatened to resign if kept in the background, stood in the way of superiors belonging to the opposite political party, in order to prevent them from making a reputation, or even took part with the men in the hope of getting into Congress by and by.11

In short, the volunteers were all one costly mass of ignorance, confusion and insubordination, said Meade; while the regular officers felt discouraged, not merely by discovering that civilians were preferred to educated soldiers for high appointments, but by finding themselves in the shadow and even under the command of men who had been discharged from West Point for incapacity or from the army for gross misconduct.10 At the height of this, General Taylor, who was disqualified by lack of experience and mental discipline for organizing an efficient staff, and therefore needed to use his own eyes and his own voice, held aloof. “I very seldom leave my tent,” he wrote on July 25, adding helplessly, “How it will all end time alone must tell.” Besides, every mail brought letters about the Presidency to distract his attention.11

Probably he saw he had blundered. On April 26 he knew that war had begun, and called upon Louisiana and Texas for soldiers with a view to the invasion of Mexico, which he must have believed, under the circumstances, that his government wished. By the rules of the service it was then his duty, as he well knew, to make requisitions for everything the campaign would require,12 and a zealous commander, gathering—as Taylor had been instructed to do—all the information he could find regarding the local conditions, might reasonably have sent on to Washington with it an able officer to assist the department. With a scorn, however, for science and vision that should have delighted Polk, Taylor did neither; but, assuming that the Mexicans would not fight—if at all—north of the mountains beyond Monterey, he determined to advance with about 6000 men. Unfortunately he neglected to have his engineers inspect the three steamboats on which his plan depended, and these proved to be worm-eaten and practically useless.13

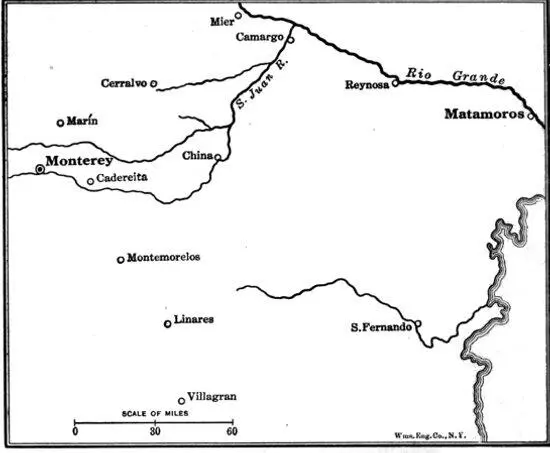

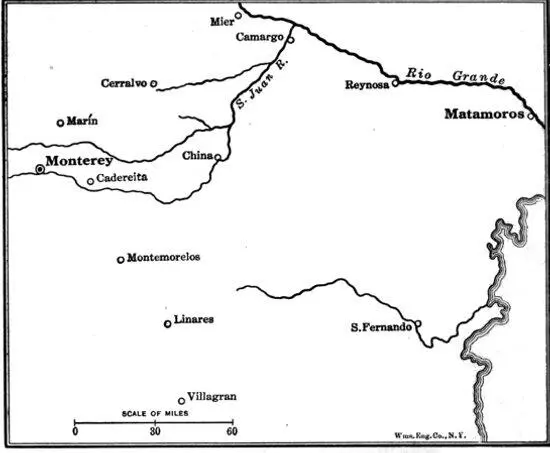

About the middle of June, boats for the Rio Grande began to be despatched from New Orleans, but—in addition to mishaps at the coast resulting from gales and the freaks of the shifting bars—a serious embarrassment soon occurred above. A direct advance against Monterey by land was deemed impracticable, because the route lacked water. Taylor had therefore planned to have his troops march to Camargo, the head of navigation toward that city, and send their supplies to that point by the river; but during the first eleven days of July rain fell heavily and flooded the country. The freshet, however, ensured a sufficient depth in the Rio Grande, and on July 6 the Seventh Infantry set out for Camargo. The distance, called about 120 miles by land, was more than twice as long by water; and the river wandered about so much that according to humorous natives a bird could never get across—always alighting on some projection of the bank from which it had risen. It proved a hard task for the light and feeble steamboats, with only green wood for the boilers, to stem the fierce current; the pilots were unacquainted with the difficulties of such navigation;14 and in making one of the sharp turns a boat was frequently caught by the current, and swept downstream or against the bank—breaking the rudder perhaps.16

But in one way or another the steamers puffed ahead past great cornfields, and occasionally there was a small village, where the people stared in wonder at the strange craft, and the girls laughed and shouted to see the soldiers throw kisses to them. After some 200 miles of this came Reynosa on a high limestone point, dominated by a heavy, stunted church tower like an ancient castle; and, farther along, the mouth of the Alcantro was passed. The country became still better now, with fertile valleys running back to the tablelands; and not only corn but potatoes, wheat, beans, and cotton could be seen. Forty miles of such a landscape, and the steamboats entered the San Juan; and after struggling on for three or four more they stopped early on July 14 at Camargo, where Captain Miles, who commanded the regiment, sent at once for the alcalde, an official who acted as mayor, judge and pater familias in a Mexican town, and formally took possession. The rest of the regular infantry pursued the same route as fast as possible, and on July 30 most of the volunteers were ordered to do so.16

August 4 Taylor himself embarked, and the next day artillery and infantry began to advance by the southern shore of the river. The road was in places deep with mud or covered with water; thick chaparral cut off the friendly breeze; the intense heat felled many a soldier, and thirst tormented all who retained their senses; but after a time the plan of moving by night lessened the suffering, and at last the painful march was achieved. The cavalry and wagons also proceeded in due course to the general rendezvous;15 and meanwhile Mier, a hill town only a short distance from the Rio Grande, was occupied without resistance on July 31.16

Camargo, a place of perhaps 5000 inhabitants, was said to be some 400 miles from the Gulf by water. It stood well up on the right bank of the river, here about one hundred yards in width; but the recent freshet, rising to an unprecedented height, had nearly destroyed it, replacing houses and gardens with about a foot of mud. This was dug away, and the banks were cleared of vegetation; “acres and acres” of tents rose; and by the end of August some 15,000 men were encamped along the San Juan for a distance of three miles or so up and down and several hundred yards back, while a quantity of stores that dumfounded the Mexicans and satisfied Taylor, was gradually piled up. Worth, who had returned to his brigade at the end of May, commanded the place and insisted on firm discipline. No American trader was tolerated; and all persons caught smuggling liquor into camp suffered “a punishment cruel to use on tender skins.”17

This was well, but it did not redeem the situation. Natives regarded Camargo as the sickliest point in the region, and the freshets had made it worse. Every breath of air raised a stifling cloud of dust from the dried and pulverized mud. Barren hills of limestone cut off the breeze to a great extent and concentrated the fierce heat, frequently sending the mercury in “this hottest of all hot places,” as a soldier called the town, to 112 degrees. Scorpions, tarantulas, mosquitos and centipedes abounded. There was a plague of small frogs. “Last night the ants tried to carry me off in my sleep,” wrote a soldier. The only drinking water came from the San Juan, and it made trouble. The ignorance of the volunteers about caring for their health was fairly matched by that of their officers and medical men. Days of sweltering under a cruel sun, with nothing to do and apparently nothing to hope for, were followed by cool nights and heavy dews, the heart-rending groans of the sick, and the yelping of numberless prairie wolves. In almost all the volunteer regiments at least one third of the men were ill, wrote Meade, and in many of them, one half. The three volleys at the graves became well-nigh a continuous roll; and the “dead march” was played so often that, as an officer said, the very birds knew it. The First Tennessee, originally 1040 prime young fellows, was reduced by deaths and discharges to less than 500. “Oh, what a horror I have for Camargo,” exclaimed one of the generals; “it is a Yawning Grave Yard”; a thousand soldiers torn and mangled on the battlefield would be nothing to its suffering and dying regiments.17

Читать дальше