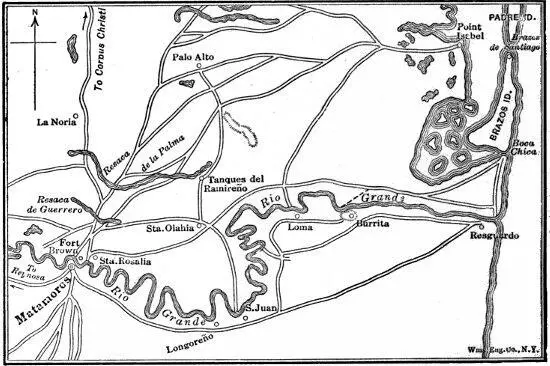

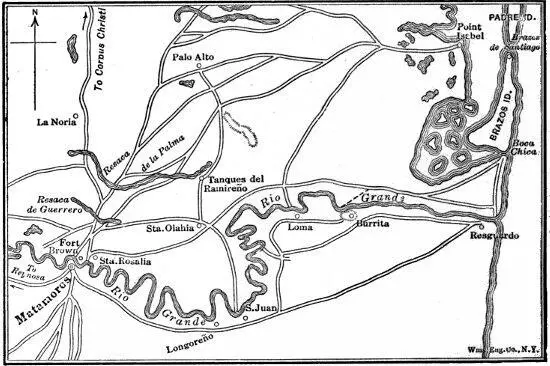

Arista, for his part, decided quite naturally, while on his way to Matamoros, that he would plant himself on the American line of communication, and prevent our army from receiving ammunition, provisions and reinforcements. Accordingly the 1600 men under Torrejón, after disposing of Thornton’s command, passed Fort Brown, held the road for some days without the knowledge of Taylor, and then by a grave blunder were drawn away, and concentrated on the Rio Grande opposite Longoreño, eight or ten miles below the city, to protect the crossing of the other troops, who proceeded to that point by several routes in order to deceive the Americans. The last day of the month Ampudia with his brigade and four guns went over; and on May 1 Arista—leaving Mejía with about 1400 men to hold Matamoros—followed with his other brigade and eight pieces. Unfortunately for him three scows of little capacity were the only boats available; and as these had been taken to Longoreño in carts by a circuitous route nearly fifteen miles in length, so as to avoid exciting our suspicions, they were not in good order. One or two, in fact, seem to have been almost useless, and hence many precious hours were lost; but at any rate the army succeeded in crossing a swift river without injury almost under the eyes of the Americans.11

By about one o’clock in the afternoon on the first of May Taylor heard that Mexicans were below him, and awoke. He saw now that Fort Brown required munitions and food, and that Point Isabel could not, even yet, resist a serious attack. Tents came down in haste; the wagon train was made ready; and at about half-past three—leaving behind the Seventh Infantry commanded by Major Brown, with Captain Lowd’s four 18-pounders, Lieutenant Bragg’s field battery and the sick, under orders to hold out as long as possible—Taylor marched for the coast. No time was lost in getting there. The troops bivouacked that night on the damp, chilly plain without fires, and early the next morning set out again. The shallow, greenish-brown lagoons rimmed with broad, flat, oozing banks of mud, the marshes full of tawny grass, and the low ridges mottled with patches of herbage and bald surfaces of gleaming dry dirt, seemed interminable; but as hours passed the now sultry air began to be streaked with salt odors, and by noon the panting troops caught the sparkle of blue waves. Fortunately they could not hear the shouts of joy in Matamoros over what was called their precipitate flight.12

As it was necessary to strengthen the defences, all the troops now exchanged their muskets for picks and shovels. May 6 the engineer in charge was authorized to continue the work by employing a hundred laborers; and at about three o’clock the next day, escorting more than 200 loaded wagons, the little army, preceded by a body of dragoons, moved out on the return march. As the small garrison of Fort Brown had provisions for at least three weeks, and the Mexicans could not be expected to attack it seriously with Taylor approaching their rear, whereas they were practically sure to be met on the road, Taylor’s best officers entreated him to gain freedom of action by leaving the train behind, which at most would have delayed it only a day or so; but he would not. No fears disturbed his mind. Reinforced with perhaps 200 men just landed at the Point, the army now with him numbered 2228, all told. Recent exercise and drill had left it in a splendid physical condition. Recollecting how long popular orators had been mocking at the “regulars,” it longed to do something. The attacks upon Cross, Walker, Porter and Thornton had exasperated its temper; nothing could have pleased the great majority of the soldiers better than a fight; and the General felt very much the same way.13

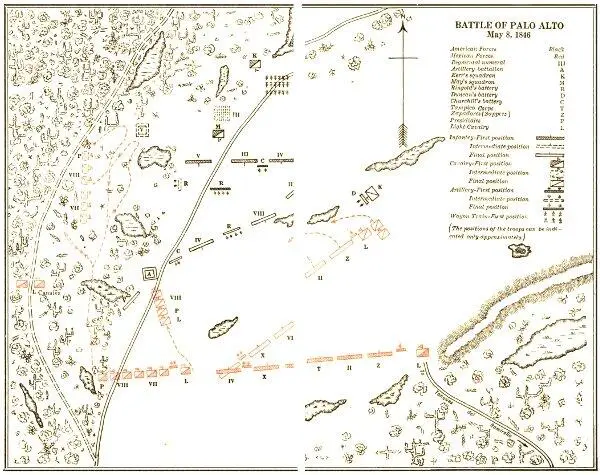

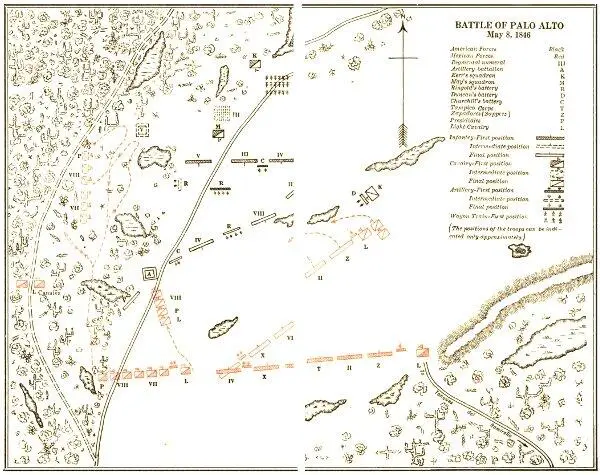

When it had made about seven miles the army bivouacked, and early the next day it resumed the march. Soon after noon, when some ten or twelve miles more had been covered, a low, dark line could be seen across the plain in front, some two or three miles away. It was the Mexican army. As the pond or water-hole of Palo Alto lay near, the tired and thirsty troops were permitted to halt, rest a little, drink and fill their canteens; and then Taylor had them posted in order of battle. At the extreme right the Fifth Infantry led by Lieutenant Colonel McIntosh was placed, and on its left in succession came Major Ringgold’s battery, the Third Infantry (Captain Morris), two 18-pounders on siege carriages under Lieutenant Churchill, and the Fourth Infantry (Major Allen). The Third and Fourth made up a brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Garland; and all the troops just mentioned, together with Twiggs’s dragoons, some 250 strong, in two squadrons led by Captains Kerr and May, formed the right wing. The other wing, known as the first brigade and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Belknap, consisted of the Artillery Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Childs, Captain Duncan’s battery, and the Eighth Infantry, posted in this order from right to left. The wagons were then assembled near the pond at the side of some woods, and Kerr was detached with his squadron to guard them.14

During these days Arista had waited for Taylor’s return; but, in order to hasten that and perhaps accomplish direct results, he had ordered the guns of Matamoros to begin cannonading Fort Brown on the morning of May 3, and two days later, believing the garrison were near starvation, sent Ampudia to invest it. For the sake of water and to cover all of the roads that might be taken by the American army, he placed himself at Los Tanques del Ramireño; and about noon on the eighth, learning of Taylor’s approach, he set out for Palo Alto, some five miles away. Shortly before gaining that point he saw through his glass blue American dragoons in the far distance, and, as quickly as he could, put his troops in position. At the extreme right were placed about 150 horse under Noriega, and then came a 4-pounder, a corps of Sappers, the Second Light Infantry, the Tampico Veteran Company and Coast Guards, five 4-pounders, the First, the Sixth and the Tenth Infantry, and finally, beyond an interval of about 400 yards and somewhat in advance, Torrejón and the rest of the cavalry—their front extended, their right strengthened with two small guns, and their left reaching beyond the Point Isabel road to a piece of chaparral on a slight elevation beside a swamp. In the rear of the line were some thickets; just behind the right wing an eminence eighteen or twenty feet high rose above chaparral; protected by this lay a watering-place; and in front there were some boggy pools and wide fields of stiff grass almost shoulder-high.14

As soon as formed, the Americans advanced in silence—the 18-pounders, drawn by oxen, following the road—while Lieutenant Blake reconnoitred the Mexican line within musket range to look for artillery. At about two o’clock Ampudia came in sight with the Fourth Infantry, commanded by Colonel Uraga, a company of Sappers, two 8-pounders, and about 400 irregular horse under Canales. Upon this Arista and his staff, a blaze of gold lace, passed rapidly down the line. It seemed strange to find in his position a tall, raw-boned man with red hair and sandy whiskers; but he showed the martial bearing of his nation, and harangued the troops with genuine Mexican eloquence. They were found ready for battle. Answering him with loud vivas they made ready their arms. The silken banners fluttered; the bands played; and at about half-past two or three o’clock, by the General’s order, his artillery opened. The hostile armies were then approximately half a mile apart; and the Mexicans—drawn out, except the cavalry, only two deep on a front about a mile in length without reserves—seemed to number 6000, though probably not more than two thirds as many.14

Читать дальше