Except near the United States the coast lands are tropical or semi-tropical; and the products of the soil, which in many quarters is extraordinarily deep and rich, are those which naturally result from extreme humidity and heat. Next comes an intermediate zone varying in general height from about 2000 to about 4000 feet, where the rainfall, though less abundant than on the coast, is ample, and the climate far more salubrious than below. Here, in view of superb mountains and even of perpetual snows, one finds a sort of eternal spring and a certain blending of the tropical and the temperate zones. Wheat and sugar sometimes grow on the same plantation, and both of them luxuriantly; while strawberries and coffee are not far apart.1

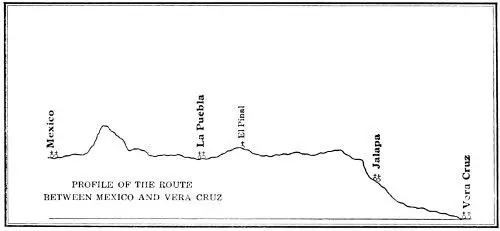

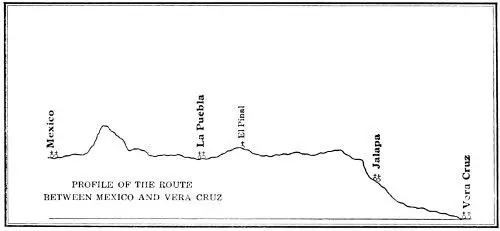

PROFILE OF THE ROUTE BETWEEN MEXICO AND VERA CRUZ

The central plateau lacks moisture and at present lacks trees. The greater part of it is indeed a semi-desert, though a garden wherever water can be supplied. During the wet season—June to October—it is covered with wild growths, but the rains merely dig huge gullies or barrancas , and almost as soon as they are over, most of the vegetation begins to wither away. The climate of the plateau is quite equable, never hot and never cold. Wheat, Indian corn and maguey—the plant from which pulque , the drink of the common people, is made—are the most important products; and at the north great herds of cattle roam. In the mountains, finally, numberless mines yield large quantities of silver, some gold, and a considerable amount of copper and lead.1

The principal cities on the eastern coast are Vera Cruz, the chief seaport, and Tampico, not far south of the Rio Grande River. In the temperate zone between Vera Cruz and Mexico lie Jalapa and Orizaba, and behind Tampico lies Monterey. On the central plateau one finds the capital reposing at an elevation of about eight thousand feet and, about seventy miles toward the southeast, Puebla; while on the other side of the capital are the smaller towns of Querétaro and San Luis Potosí toward the north, and Zacatecas and Chihuahua toward the northwest. In the middle zone of the Pacific slope rises the large city of Guadalajara, capital of Jalisco state; and along the coast below may be found a number of seaports, the most important of which are Guaymas, far to the north, Mazatlán opposite the point of Lower California, San Blas a little farther down, and Acapulco in the south.1

Exactly how large the population of Mexico was in 1845 one cannot be sure, and it included quite a number of racial mixtures; but for the present inquiry we may suppose it consisted of 1,000,000 whites, 4,000,000 Indians, and 2,000,000 of mixed white and Indian blood.2 The Spaniards from Europe, called Gachupines in Mexico, were of two principal classes during her colonial days. Many had been favorites of the Spanish court, or the protégés of such favorites, and had exiled themselves to occupy for a longer or shorter time high and lucrative posts; but by far the greater number were men who had left home in their youth—poor, but robust, energetic and shrewd—to work their way up. With little difficulty such immigrants found places in mercantile establishments or on the large estates. Merciless in pursuit of gain yet kind to their families, faithful to every agreement, and honest when they could afford to be, they were intrinsically the strongest element of the population, and almost always they became wealthy.3

Their sons, poorly educated, lacking the spur of poverty, and finding themselves in a situation where idleness and self-indulgence were their logical habits, commonly took “ Siempre alegre ” (Ever light-hearted) for their motto, and spent their energy in debauchery and gambling. To this result their own fathers, while disgusted with it, usually contributed. Spanish pride revolted at the ladder of subordination by which these very men had climbed. They felt ambitious to make gentlemen of their sons, and some easy position in the army, church or civil service—or, in default of it, idleness—was the career towards which they pointed; and naturally the heirs to their wealth, whose ignoble propensities had prevented them from acquiring efficiency or sense of responsibility, made haste, on getting hold of the paternal wealth, to squander it. If the pure whites, with some exceptions of course, fell into this condition, nothing better could fairly be expected of those who were partly Indian; and before the revolution it was almost universally felt in Spain and among the influential class of colonials themselves, that nothing of much value could be expected of Creoles, as the whites born in Mexico and the half-breeds were generally called. The achievement of independence naturally tended to increase their self-respect, broaden their views and stimulate their ambition; but the less than twenty-five years that elapsed between 1821 and 1846, when the war between Mexico and the United States began, were not enough to transform principles, reverse traditions and uproot habits.3

The pure-blooded Indians—of whom there were many tribes, little affiliated if at all—had changed for the worse considerably since the arrival of the whites. In their struggles against conquest and oppression the most intelligent, spirited and energetic had succumbed, and the rest, deprived of strength, happiness, consolation and even hope, and aware that they existed merely to fill the purses or sate the passions of their masters, had rapidly degenerated. Their natural apathy, reticence and intensity were at the same time deepened. While apparently stupid and indifferent, they were capable of volcanic outbursts. Though fanatically Christian in appearance, they seem to have practiced often a vague nature worship under the names and forms of Catholicism. Indeed they were themselves almost a part of the soil, bound in soul to the spot where they were born; and, although their women could put on silk slippers to honor a church festival and every hut could boast a crucifix or a holy image, they lived and often slept beside their domestic animals with a brutish disregard for dirt.3

Legally they had the rights of freemen and were even the wards of the government, and a very few acquired education and property; but as a rule they had to live by themselves in little villages under the headship of lazy, ignorant caciques and the more effective domination of the priests. As the state levied a small tax upon them and the Church several heavy ones, their scanty earnings melted fast, and if any surplus accumulated they made a fiesta in honor of their patron saint, and spent it in masses, fireworks, drink, gluttony and gambling. When sickness or accident came they had to borrow of the landowner to whose estate they were attached; and then, as they could not leave his employ until the debt had been discharged, they not only became serfs, but in many cases bequeathed their miserable condition to their children. Silent and sad, apparently frail but capable of great exertion, trotting barefooted to and from their huts with their coarse black hair flowing loosely or gathered in two straight braids, watching everything with eyes that seemed fixed on the ground, loving flowers much but a dagger more, fond of melody but preferring songs that were melancholy and wild, always tricky, obstinate, indolent, peevish and careless yet affectionate and hospitable, often extracting a dry humor from life as their donkeys got nourishment from the thistles, they went their wretched ways as patient and inscrutable as the sepoy or the cat—infants with devils inside.3

At the head of the social world stood a titled aristocracy maintained by the custom of primogeniture. But as the nobles were few in number, and for a long time had possessed no feudal authority, their influence at the period we are studying depended mainly upon their wealth. Next these came aristocrats of other kinds. Some claimed the honor of tracing their pedigree to the conquerors, and with it enjoyed great possessions; and others had the riches without the descent. The two most approved sources of wealth were the ownership of immense estates and the ownership of productive mines. On a lower level stood certain of the rich merchants, and lower still, if they were lucky enough to gain social recognition, a few of those who acquired property by dealing in the malodorous government contracts. To these must be added in general the high dignitaries of the church, the foreign ministers, the principal generals and statesmen and the most notable doctors and lawyers. Such was the upper class.4

Читать дальше