“Ayrton was not with them!” said Herbert.

“No,” answered Pencroft, “and if he was not with them, it was because the wretches had already murdered him! but then these rascals have not a den to which they may be tracked like tigers!”

“No,” replied the reporter; “it is more probable that they wander at random, and it is their interest to rove about until the time when they will be masters of the island!”

“The masters of the island!” exclaimed the sailor; “the masters of the island!” he repeated, and his voice was choked, as if his throat was seized in an iron grasp. Then in a calmer tone, “Do you know, Captain Harding,” said he, “what the ball is which I have rammed into my gun?”

“No, Pencroft!”

“It is the ball that went through Herbert’s chest, and I promise you it won’t miss its mark!”

But this just retaliation would not bring Ayrton back to life, and from the examination of the footprints left in the ground, they must, alas! conclude that all hopes of ever seeing him again must be abandoned.

That evening they encamped fourteen miles from Granite House, and Cyrus Harding calculated that they could not be more than five miles from Reptile Point.

And, indeed, the next day the extremity of the peninsula was reached, and the whole length of the forest had been traversed; but there was nothing to indicate the retreat in which the convicts had taken refuge, nor that, no less secret, which sheltered the mysterious unknown.

Table of Contents

Exploration of the Serpentine Peninsula—Encampment at the Mouth of Falls River—Gideon Spilett and Pencroft reconnoitre—Their Return—Forward, All!—An open Door—A lighted Window—By the Light of the Moon!

The next day, the 18th of February, was devoted to the exploration of all that wooded region forming the shore from Reptile End to Falls River. The colonists were able to search this forest thoroughly, for, as it was comprised between the two shores of the Serpentine Peninsula, it was only from three to four miles in breadth. The trees, both by their height and their thick foliage, bore witness to the vegetative power of the soil, more astonishing here than in any other part of the island. One might have said that a corner from the virgin forests of America or Africa had been transported into this temperate zone. This led them to conclude that the superb vegetation found a heat in this soil, damp in its upper layer, but warmed in the interior by volcanic fires, which could not belong to a temperate climate. The most frequently-occurring trees were kauries and eucalypti of gigantic dimensions.

But the colonists’ object was not simply to admire the magnificent vegetation. They knew already that in this respect Lincoln Island would have been worthy to take the first rank in the Canary group, to which the first name given was that of the Happy Isles. Now, alas! their island no longer belonged to them entirely; others had taken possession of it, miscreants polluted its shores, and they must be destroyed to the last man.

No traces were found on the western coast, although they were carefully sought for. No more footprints, no more broken branches, no more deserted camps.

“This does not surprise me,” said Cyrus Harding to his companions. “The convicts first landed on the island in the neighbourhood of Flotsam Point, and they immediately plunged into the Far West forests, after crossing Tadorn Marsh. They then followed almost the same route that we took on leaving Granite House. This explains the traces we found in the wood. But, arriving on the shore, the convicts saw at once that they would discover no suitable retreat there, and it was then that, going northwards again, they came upon the corral.”

“Where they have perhaps returned,” said Pencroft.

“I do not think so,” answered the engineer, “for they would naturally suppose that our researches would be in that direction. The corral is only a store-house to them, and not a definitive encampment.”

“I am of Cyrus’ opinion,” said the reporter, “and I think that it is among the spurs of Mount Franklin that the convicts will have made their lair.”

“Then, captain, straight to the corral!” cried Pencroft. “We must finish them off, and till now we have only lost time!”

“No, my friend,” replied the engineer; “you forget that we have a reason for wishing to know if the forests of the Far West do not contain some habitation. Our exploration has a double object, Pencroft. If, on the one hand, we have to chastise crime, we have, on the other, an act of gratitude to perform.”

“That was well said, captain,” replied the sailor; “but, all the same, it is my opinion that we shall not find that gentleman until he pleases.”

And truly Pencroft only expressed the opinion of all. It was probable that the stranger’s retreat was not less mysterious than was he himself.

That evening the cart halted at the mouth of Falls River. The camp was organised as usual, and the customary precautions were taken for the night. Herbert, become again the healthy and vigorous lad he was before his illness, derived great benefit from this life in the open air, between the sea-breezes and the vivifying air from the forests. His place was no longer in the cart, but at the head of the troop.

The next day, the 19th of February, the colonists, leaving the shore, where, beyond the mouth, basalts of every shape were so picturesquely piled up, ascended the river by its left bank. The road had been already partially cleared in their former excursions made from the corral to the west coast. The settlers were now about six miles from Mount Franklin.

The engineer’s plan was this:—To minutely survey the valley forming the bed of the river, and to cautiously approach the neighbourhood of the corral; if the corral was occupied, to seize it by force; if it was not, to intrench themselves there and make it the centre of the operations which had for their object the exploration of Mount Franklin.

This plan was unanimously approved by the colonists, for they were impatient to regain entire possession of their island.

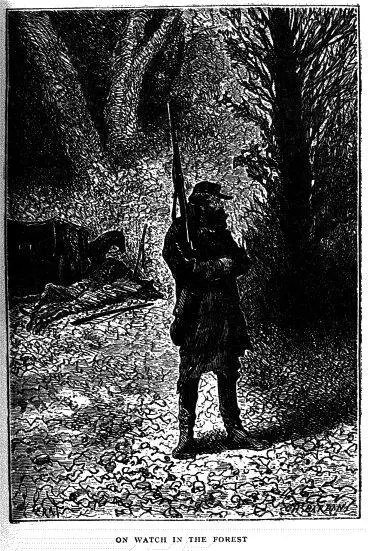

They made their way along the narrow valley separating two of the largest spurs of Mount Franklin. The trees, crowded on the river’s bank, became rare on the upper slopes of the mountain. The ground was hilly and rough, very suitable for ambushes, and over which they did not venture without extreme precaution. Top and Jup skirmished on the flanks, springing right and left through the thick brushwood, and emulating each other in intelligence and activity. But nothing showed that the banks of the stream had been recently frequented—nothing announced either the presence or the proximity of the convicts. Towards five in the evening the cart stopped nearly 600 feet from the palisade. A semicircular screen of trees still hid it.

It was necessary to reconnoitre the corral, in order to ascertain if it was occupied. To go there openly, in broad daylight, when the convicts were probably in ambush, would be to expose themselves, as poor Herbert had done, to the fire-arms of the ruffians. It was better, then, to wait until night came on.

However, Gideon Spilett wished without further delay to reconnoitre the approaches to the corral, and Pencroft, who was quite out of patience, volunteered to accompany him.

“No, my friends,” said the engineer, “wait till night. I will not allow one of you to expose himself in open day.”

“But, captain,” answered the sailor, little disposed to obey.

Читать дальше