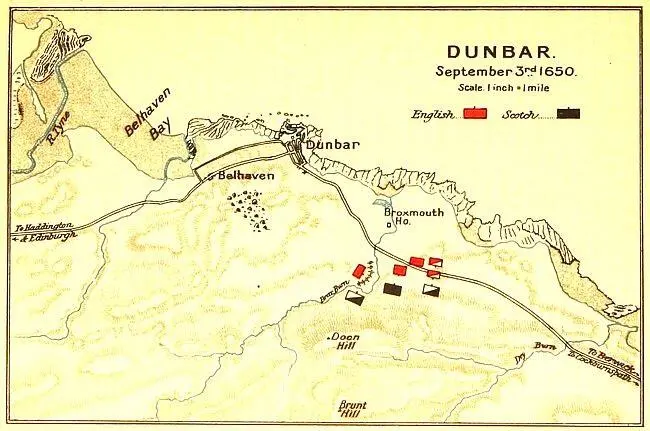

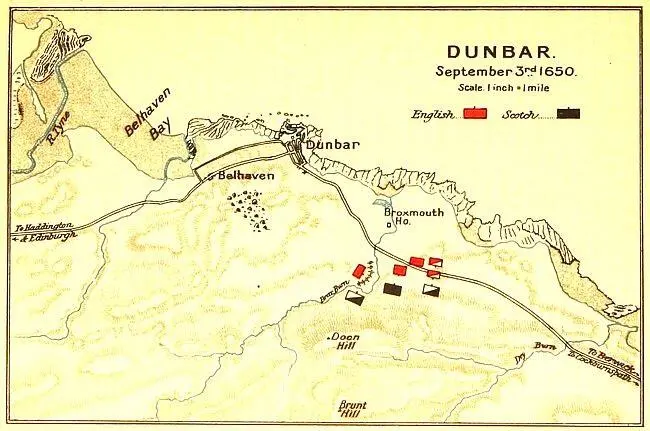

Rain fell in torrents all through the night, and the Scotch picquets laid themselves down to sleep with what comfort they could among the corn-shocks. The English, as ever even during the worst and most disorderly of retreats, had recovered themselves at the prospect of battle. At four the moon rose and found Lambert already hard at work. The bulk of the force, six out of eight regiments of horse and three and a half regiments of foot, was moved down to the extreme English left. Five regiments of horse under Lambert were to cross the burn by Broxmouth House and attack the Scottish cavalry in front; three regiments of foot and one of horse, all picked corps, were to cross the water farther down and sweep round upon its right flank. Cromwell himself took command of this turning movement, and the regiment of horse which he took with him was that which he had made six years before on the model of his own "lovely company." The remainder of the force with the artillery was stationed along the edge of the trench of the Broxburn to check any movement of the enemy's centre and left.

The light was beginning to creep over the sea before Lambert had posted the artillery to his liking. There was some stir in the Scotch camp; a trumpet sounded boute-selle ; and Cromwell, fearful lest the enemy should gain time to change position, grew impatient for Lambert's coming. At last he came, and both columns moved off. Lambert's regiments of horse advanced to the burn; and then the trumpets rang out, and the troopers dashed across the water and poured up the opposite slope to the attack. The Scots, though unprepared, met them gallantly enough. Foreigners would have called them ill-equipped, for they carried lances, an obsolete weapon, in their front rank; but the lance was in place in the shock-combat which Cromwell had taught to the English cavalry, and the first onset of the English horse was borne back across the burn. The supports came quickly up and the fight was renewed, though against heavy odds, for the Scots could bring infantry and guns to the aid of their horse, which the English could not yet. But while the combat of cavalry was still swaying to and fro, the infantry of Cromwell's turning column came up steady and inexorable upon the flank of the Scots. Still Leslie's gallant men fought on for a short time undismayed. They had been faultily disposed, as Cromwell had noted, and could not easily change front,[180] but they met the new attack as best they might and even checked the leading regiment of English infantry. But Cromwell's own regiment of foot came up in support, strode grimly forward straight to push of pike, and swept the stoutest corps of Scottish infantry into rout.

DUNBAR.

September 3 rd1650.

Then the Scots lost heart and wavered; the English, horse and foot, gathered themselves up for a final terrible charge; and the Scottish cavalry, reeling back upon the foot, carried it away in choking disorder towards the gorge. Meanwhile Cromwell was urging his third regiment of foot to the left, always farther to the left; and as, panting and breathless, they climbed the lower slopes of the hill they saw the whole length of the battle spread out before them and the Scotch all in confusion. "They run, I profess, they run!" cried Oliver as he looked down. And while he spoke the sun leaped up over the sea, and flashed beneath the canopy of smoke on darting pikes and flickering blades and glancing casques and swaying cuirasses, as the red-coats rolled the broken waves of the Scottish army before them. "Now let God arise and let His enemies be scattered," cried Cromwell in exultation, for the victory was won. The Scots, wedged tighter and tighter between hills and stream, were caught like rats in a pit, and like rats they ran desperately and aimlessly up the steep slope, only to be caught or turned back by the English skirmishers above them. Their horse fled as best they could with the English cavalry spurring after them, till Cromwell ordered a rally. While the broken ranks were reforming he sang the hundred and seventeenth Psalm, the chorus swelling louder and louder behind him as trooper after trooper fell into his place. Then the psalm gave way to the sharp word of command, and the horse trotted away once more to the pursuit past Dunbar and Belhaven even to Haddington. Three thousand of the Scots fell in the field; ten thousand prisoners, with the whole of the artillery and baggage and two hundred colours, were taken. It was the greatest action fought by an English army since Agincourt.

Cromwell lost no time in following up his success. On the day after the battle he sent Lambert forward with six regiments of horse to Edinburgh, and occupied the port of Leith and the whole of the town, except the Castle, without resistance. Leaving sufficient men to blockade the Castle and hold the works at Leith he pushed on against Leslie, who had entrenched himself with five thousand men at Stirling; but finding his position unassailable he returned to Edinburgh and busied himself with the reduction of the Castle, while Lambert completed the subjugation of the West. In the middle of September the Castle surrendered, and therewith all Scotland south of the Forth and Clyde was subject to the English.

1651.

At Westminster the joy over the victory of Dunbar was enthusiastic, and found vent in the grant of a medal[181] and of a gratuity to every man who had fought in the campaign. This, the first medal ever issued to an English army, bore, in spite of his protests, the effigy of Cromwell upon the obverse, no unfitting memorial of the first founder of our Army of to-day. But the struggle even now was not yet over. Royalist Scotland had been beaten at Preston, the Scotland of the Covenant at Dunbar; but Charles Stuart was able, by unscrupulous lying and shameless hypocrisy, to unite both for a last effort in his cause, and to gather a new army around that of David Leslie at Stirling. Accordingly on the 4th of February 1651 Cromwell left his winter-quarters for Stirling, but was compelled by the severity of the weather to retreat, with no further result to himself than a dangerous attack of fever and ague, which kept him on the sick-list until June.

On the 25th of June the English army was concentrated on the Pentland Hills, and from thence marched once more to Stirling. Leslie, true to the tactics which had proved so successful in the previous year, had occupied an impregnable position which no temptation could induce him to quit. After a fortnight's manœuvring, therefore, Cromwell decided, like Surrey before Flodden, to move round Leslie's left flank and to cut off his supplies from the north. It is plain, from the fact that Monk had been engaged in operations for the reduction of Inchgarvie and Burntisland on the northern shore of the Firth of Forth, that Cromwell's plans for this movement were fully matured.

July 19–20.

The first step was to send Lambert across the Firth with four thousand men to entrench himself at Queensferry. Leslie met this move by detaching a slightly inferior force against Lambert, which was utterly and disastrously routed, with a loss of five-sixths of its numbers. Ten days later Inchgarvie and Burntisland fell into Cromwell's hands, and, his new base being thus secured, he advanced quickly into Fife. Meanwhile he sent orders to General Harrison, whom he had left at Edinburgh with a reserve of three thousand horse, that he was to move at once to the English border in the event of Leslie's marching southward. By the 2nd of August he had received the surrender of Perth, but, even before he could sign the capitulation, intelligence reached him that the Scots had quitted Stirling two days before and were pouring down to the border. Leaving five or six thousand men with Monk to reduce Stirling, he at once hurried off in pursuit.

Читать дальше