1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...45 All three of these ethics are still prevalent. The Resource Conservation Ethic resonates with the natural resource–based industries and the associated government agencies that regulate them (although some would argue a profit motive is more dominant than a conservation ethic). Some environmental organizations are wedded to the Romantic‐Transcendental Preservation Ethic, reflecting a membership that uses nature primarily for spiritual rejuvenation. Consider the Wilderness Society, for example, and its frequent allusions to the spiritual reasons for “saving” nature. The Evolutionary‐Ecological Land Ethic characterizes various groups that try to find a practical balance between the needs of people and nature, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature or The Nature Conservancy.

In the conclusion to his essay, Callicott (1990) asks some provocative questions. If people are valid members of the biotic community as Leopold asserts, why do we turn to landscapes without people (at least without industrial era people) to set benchmarks for what is natural? If beavers and reef‐building corals can shape landscapes in positive ways, why can’t people? Can people improve natural ecosystems? Can they promote and generate biological diversity? These are not simple issues, and we will return to them frequently in this book because this dynamic, often difficult, interface between people and nature is the crux of conservation and conservation biology.

What Is Conservation Biology?

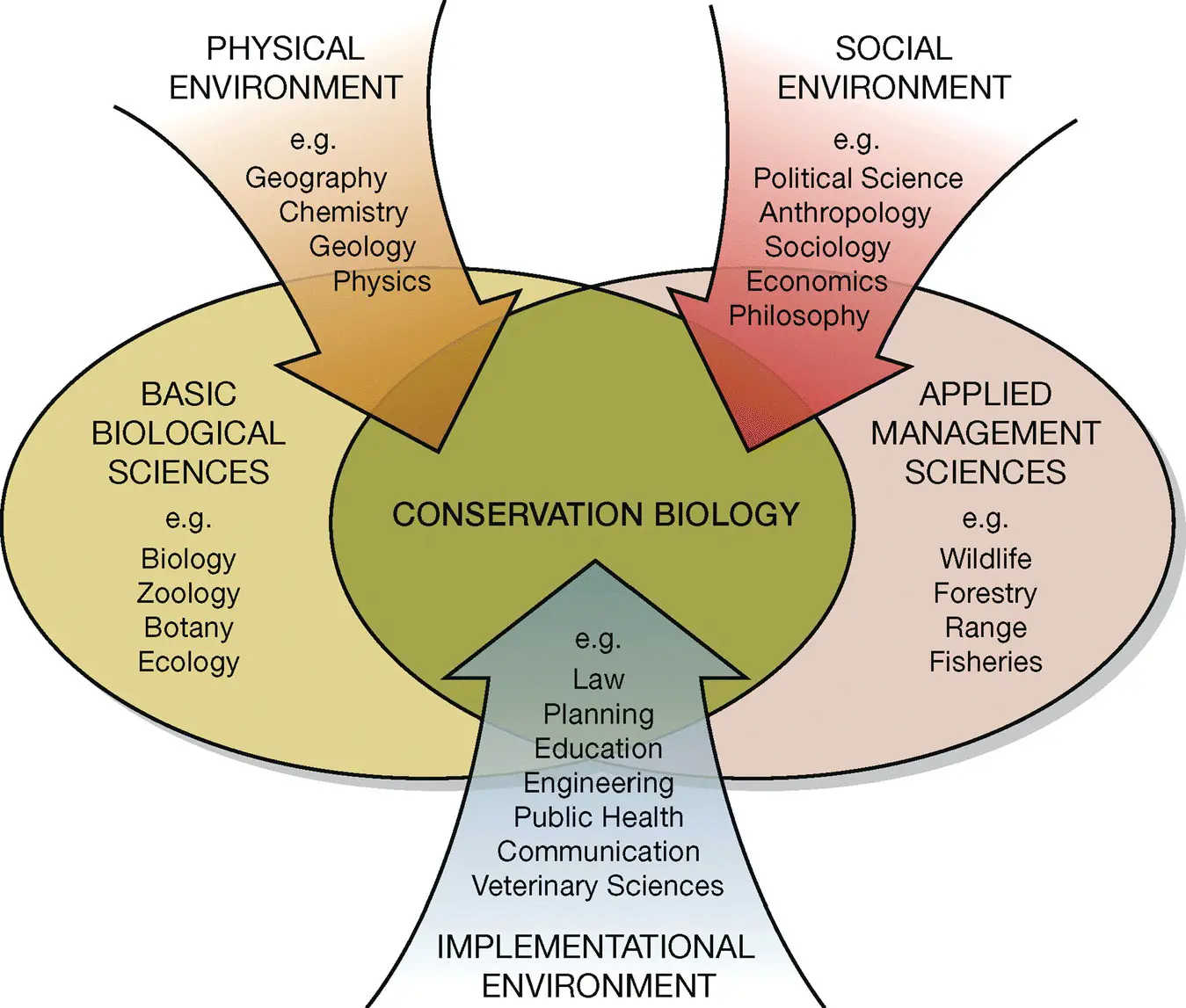

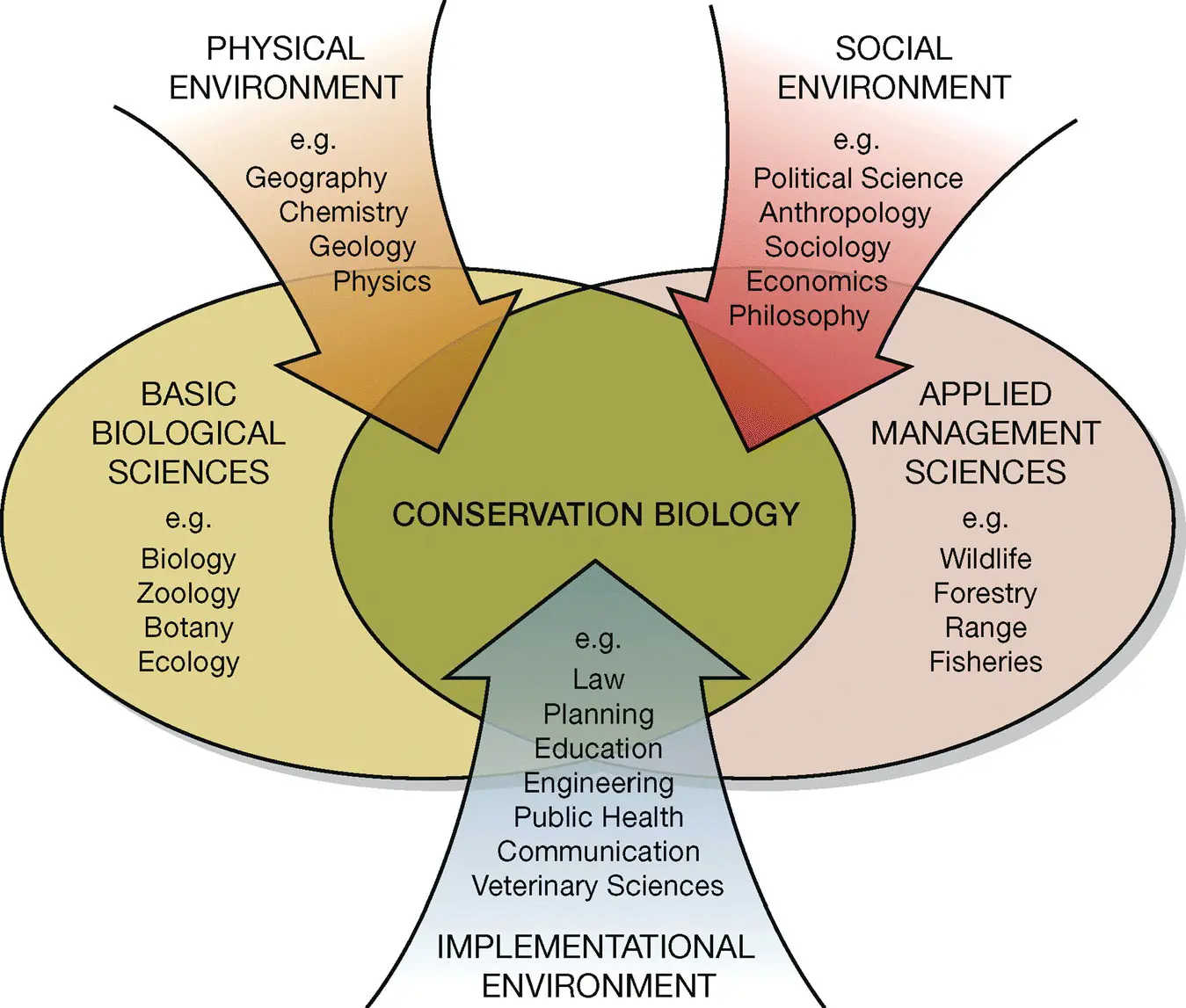

So where does conservation biology fit among these larger issues? Conservation biology is the applied science of maintaining the Earth’s biological diversity. A simpler, more obvious definition – biology as applied to conservation issues – would be misleading because conservation biology is both less and more than this. It is narrower than this definition because there are many biological aspects of conservation, such as biological research on how to grow timber faster, improve water quality, or graze more livestock, that are only tangentially related to conservation biology. On the other hand, it reaches far beyond biology into disciplines such as philosophy, economics, and sociology that are concerned with the social environment in which we practice conservation, the reasons we are motivated to maintain biodiversity, and disciplines such as law and education that shape the ways we implement conservation (Jacobson 1990 ; Soulé 1985). Fifty years ago, maintaining biological diversity simply meant saving endangered species from extinction and was considered a small component of conservation, completely overshadowed by forestry, soil and water conservation, fish and game management, and related disciplines. Now we know that we need a healthy and diverse biota for our own well‐being. And with so many species at risk of extinction and the idea of biological diversity extending to genes, ecosystems, and other biological entities, conservation biology has moved into the spotlight as the crisis discipline focused on saving life on Earth, perhaps the major issue of our time (Wilson 1992).

Conservation biology is best conceptualized as an amalgamation of disciplines as depicted in Fig. 1.4(Jacobson 1990). It sits between basic biological sciences and natural resource sciences because it originated largely with biologists who have created a new natural resource science. It is different from traditional natural resource sciences because it places relatively greater emphasis on all forms of life and their intrinsic value, compared with traditional other natural resource sciences that usually focus on a few economically valuable species (Soulé 1985). Like natural resource sciences, conservation biology is influenced by the earth sciences because it addresses issues with strong environmental linkages. Finally, conservation biology depends heavily on social sciences, law, education, and other disciplines because it operates in the world of human socio‐economic–political institutions and seeks to change those institutions to allow people to coexist with the rest of the world’s species.

Figure 1.4 A schematic view of the relationship between conservation biology and other disciplines.

(Jacobson 1990/John Wiley & Sons)

This model also illustrates how any student wishing to become a conservation biologist needs to focus on courses in the basic biological sciences and the applied sciences of natural resource management while acquiring a substantial understanding of the subjects that shape the legal, policy, social and cultural arena within which conservation operates. This has also led to a growing role and critical role for students with a primary background in law, economics, communication, education and so on, and a secondary foundation in biology. In fact, the term “conservation science” is increasingly favored rather than “conservation biology” because the field is about so much more than biology.

A Brief History of Conservation Biology

The deepest, longest roots of conservation biology are widespread but its emergence as a discipline is usually attributed to the First International Conference on Conservation Biology held in San Diego, California, in 1978, and to the book that followed, Conservation Biology (Soulé and Wilcox 1980). Eight years after this small beginning the Society for Conservation Biology was formed, and it launched a new journal, Conservation Biology , in 1987 ( Fig. 1.5). The society and its journal flourished, and universities, foundations, private conservation groups, and government agencies nurtured this growth with an array of conservation biology programs (Jacobson 1990 ; Meine et al. 2006).

Figure 1.5 The Society for Conservation Biology began publishing Conservation Biology in May 1987 and held its first conference that June.

The founders of conservation biology had many more links to institutions of basic biological sciences (e.g. genetics, zoology, botany) than to natural resource management institutions and they wove some novel and diverse intellectual threads into the discipline’s tapestry. Ideas from evolutionary biology, population dynamics, landscape ecology, and biogeography provided a new understanding of the diversity of life, its origins and maintenance, how it is distributed around the globe, and what threatens it.

By forming a new professional society dedicated to the maintenance of biological diversity, conservation biologists partly overlapped the domain of some older professional societies. This was especially true of The Wildlife Society, which, on the very first page of The Journal of Wildlife Management, described wildlife management as “part of the greater movement for conservation of our entire native flora and fauna” (Bennitt et al. 1937). Today wildlife managers place an ever‐growing emphasis on endangered and nongame species, including reptiles, amphibians, and sometimes even invertebrates and plants. However, much of their attention, arguably most, is still focused on “game” species, in large part because most of the funding for wildlife management agencies comes from the fees hunters and anglers are required to pay. Perhaps, if more wildlife managers had reached out to embrace all forms of life that are wild, not just the vertebrates, and to work with a constituency of all people who care about nature, not just hunters and anglers, then conservation biology might never have arisen as a separate discipline. This is especially apparent if one defines “wildlife” as “all forms of life that are wild,” a definition that overlaps substantially with biodiversity. Notably, the first institution to apply science to conservation was the “Roosevelt Wild Life Station,” established in 1919 to integrate science, natural history, and natural resources management for training a new generation of students to implement this new idea of “conservation” of “wild life.” To be clear that this book uses a broad definition, we retain the original, two‐word spelling, “wild life.” As you can see, these terms “wildlife,” “wild life,” “biological diversity,” and “biodiversity” have a long and inter‐related history and still remain in use in different contexts.

Читать дальше