Sarah Thilges PhDSection of Psychosocial Oncology Loyola University Medical Center Maywood, IL, USA

André Tichelli MDDivision of Hematology University Hospital Basel Basel, Switzerland

Mihkaila Wickline MDSeattle Cancer Care Alliance Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Seattle, WA, USA

Lori Wiener, PhD, DCSW, LCSW‐CPsychosocial Support and Research Program Center for Cancer Research Pediatric Oncology Branch NIH Bethesda, MD, USA

John R. Wingard MDDivision of Hematology & Oncology University of Florida College of Medicine Gainesville, FL, USA

SECTION 1 Late effects concepts

CHAPTER 1 Introduction to long‐term survivorship after hematopoietic cell transplantation

Bipin N. Savani1 and André Tichelli2

1Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

2Division of Hematology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) provides curative therapy for a variety of diseases. Over the past several decades, significant advances have been made in the field of HCT and now HCT has become an integral part of treatment modality for a variety of hematologic malignancies and some nonmalignant diseases. HCT remains an important treatment option for a wide variety of hematologic and nonhematologic disorders, despite recent advances in the field of immunologic therapies. Factors driving this growth include expanded disease indications, greater donor options (expanding unrelated donor registries and haploidentical HCT), and accommodation of older and less fit recipients [1,2‐4].

The development of less toxic pretransplant conditioning regimens, more effective prophylaxis of graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD), improved infection control, and other advances in transplant technology have resulted in a rapidly growing number of transplant recipients surviving long‐term free of the disease for which they were transplanted. The changes over decades in the transplant recipient population and in the practice of HCT will have almost inevitably altered the composition of the long‐term survivor population over time. Apart from an increasingly older transplant recipient cohort, the pattern of transplant indications has shifted from the 1990s when chronic myeloid leukemia made up a significant proportion of allo‐HCT indications. Changes in cell source, donor types, conditioning regimens, GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care have all occurred, with ongoing reductions in both relapse and non‐relapse mortality (NRM) have been demonstrated [5–10].

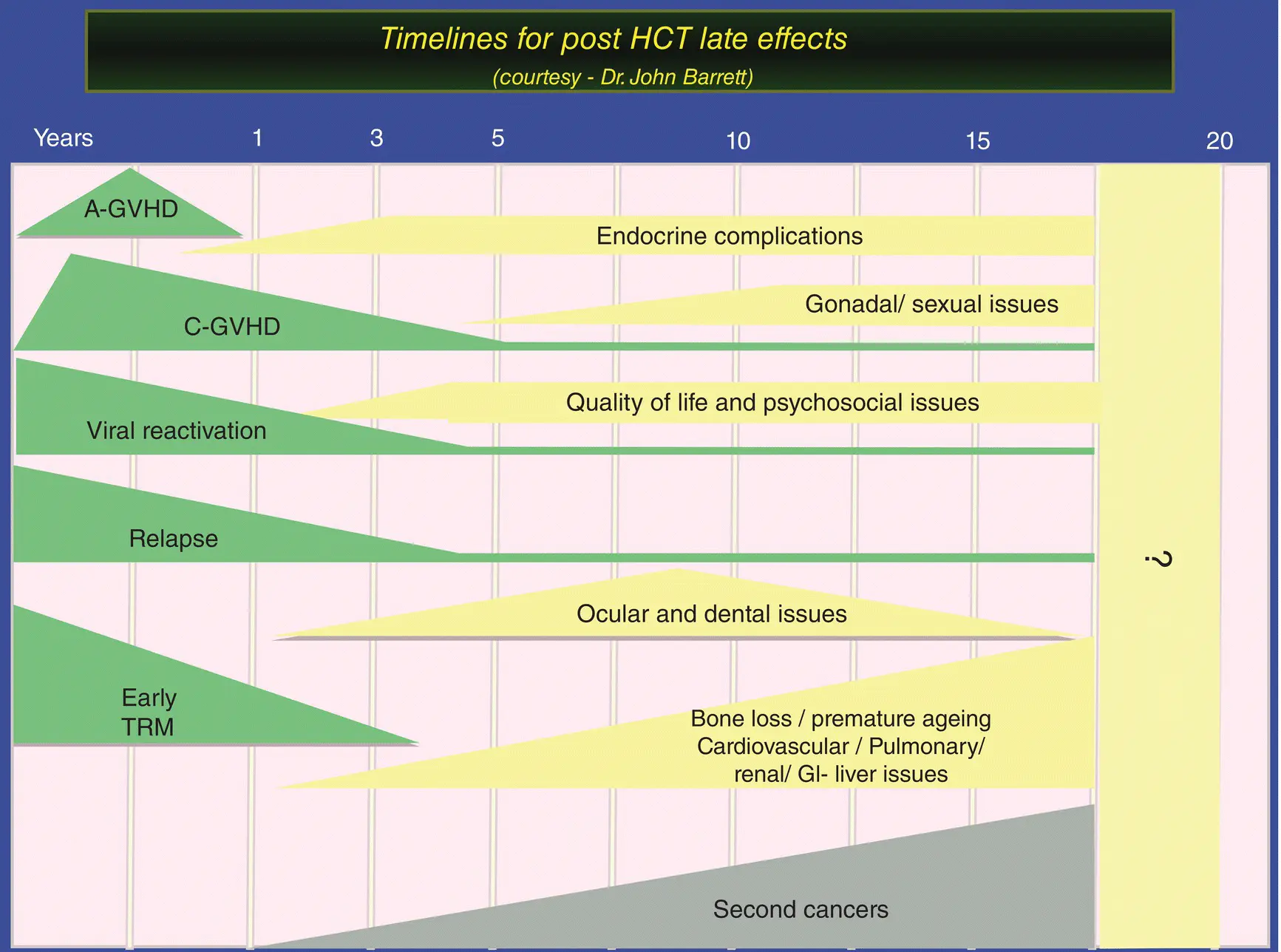

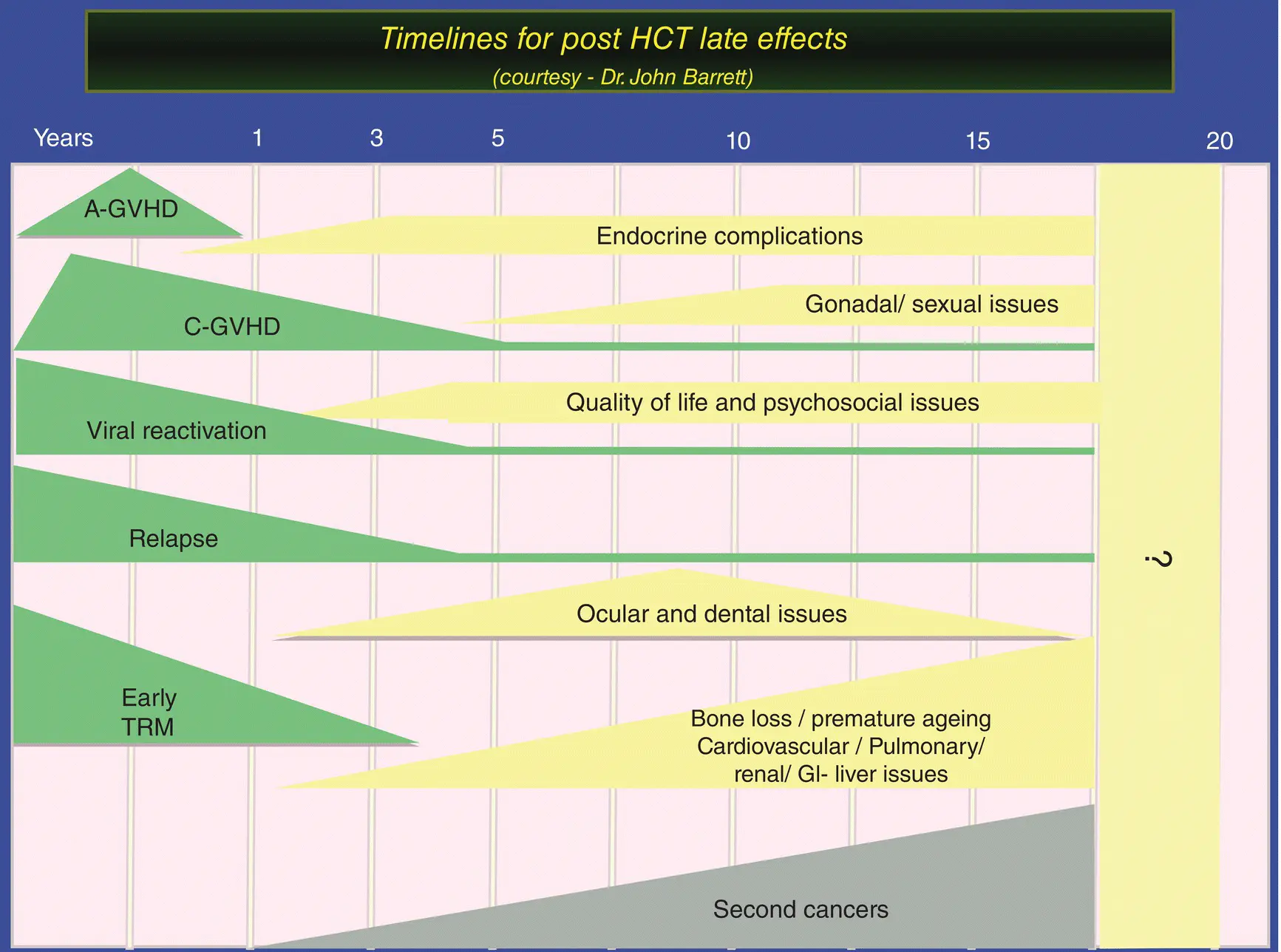

These patients have increased risks for a variety of late complications, which can cause morbidity and mortality ( Figure 1.1). Most long‐term survivors return to the care of their local hematologists/oncologists or primary care physicians, who may not be familiar with specialized monitoring and management of long‐term complications after HCT for this patient population. As HCT survivorship increases, the focus of care has shifted to the identification and treatment of long‐term complications that may affect quality of life and long‐term morbidity and mortality [11–13].

Preventive care, as well as early detection and treatments, are important aspects to reducing morbidity and mortality in long‐term survivors after allo‐HCT [4,14‐17]. The second edition of the book Blood and Marrow Transplantation Long‐Term Management: Prevention and Complications updates our knowledge on diagnosis, screening, treatment, and long‐term surveillance of long‐term survivors after HCT and shall meet the long‐term follow‐up standard operative practice (SOP) requirement of Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT)/ Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT‐EBMT (JACIE) standards [17].

Rapidly rising numbers of long‐term transplant survivors

Since the first three cases of successful allo‐HCT in 1968, the number of HCTs performed annually has increased steadily over the past several decades and continues to do so each year [1–3]. Advances in HCT practice and supportive care have led to improved outcomes and an increasing number of long‐term HCT survivors.

Historically, the limitation of allo‐HCT has been transplant‐related mortality (TRM) and the availability of a compatible donor. In order to offer the curative allo‐HCT treatment option in most patients, safer regimens with acceptable GVHD‐associated morbidity and TRM are preferred, and donor availability have been expanded. In this era, a stem cell source can be found for virtually all patients who have an indication to receive allo‐SCT. All of these advances result in steadily increasing numbers of long‐term survivors after HCT, creating an expanding pool of children, and young and mature adults who are at risk of long‐term complications of HCT [18].

Figure 1.1 Timelines for post‐HCT late effects.

(Source: Courtesy of Prof. John Barrett.)

Long‐term issues in long‐term survivors

For long‐term survivors (beyond 2 years post‐HSCT), the prospect for long‐term survival is excellent (85% at 10 years after HSCT). Yet, among long‐term survivors, mortality rates are four‐ to nine‐fold higher than observed in an age‐adjusted general population for at least 30 years after HCT, yielding an estimated 20–30% lower life expectancy compared with someone who has not been transplanted [19,20]. The most common causes of excess deaths, other than recurrent malignancy, are chronic GVHD (cGVHD), infections, second malignancies, respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular disease and many other late effects reviewed in this book.

cGVHD is a multisystem chronic alloimmune and autoimmune disorder that occurs later after allo‐HCT. It is characterized by immunosuppression, immune dysregulation, decreased organ function, significant morbidity, and impaired survival. A number of patients require continued immunosuppressive treatment beyond 5 years from the initial diagnosis of cGVHD. Therefore, it is not surprising that corticosteroid and other immunosuppressive therapies are major contributors of late complications after allo‐HCT. If not treated adequately, and in severe cases, cGVHD can result in major disability related to keratoconjunctivitis sicca, pulmonary insufficiency due to bronchiolitis obliterans, or restrictive lung disease related to scleroderma or fasciitis, as well as joint contractures, skin ulcers, esophageal and vaginal stenosis, and many other long‐term complications [4,21].

Several factors impact on recovery from and late effects of HCT, including previous therapy for the underlying disease, pretransplant co‐morbidities and psychosocial status, intensity of the transplant conditioning regimen and, most importantly, duration of cGVHD and immunosuppressive therapy [18,22]. Other complications are related to the prolonged use of glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive drugs, and many are multifactorial in etiology. Side effects of the treatment of acute complications early after HCT (e.g., the use of corticosteroids) may also contribute to long‐term complications. Nearly all organ systems can be affected by late effects of HCT. However, the burden of late effects can greatly differ among long‐term survivors, primarily depending on patient‐ and transplant‐related risk factors.

Developing resources and a guide for long‐term survivors

Читать дальше