Linking the concept of ecological sustainability to that of economic development appears contradictory. This is particularly pertinent where sustainability and development clash – for example, when considering new roads or retail sites, it is often the case that the prospect of new jobs and economic prosperity means sustainability takes second place, especially in times of economic recession. This is even more pronounced for governments in developing countries, which are badly in need of more economic activity. In recent years, ideas of environmental justice and ecological citizenship have come to the fore (as we see below), partly as a result of the severe problems associated with the concept and practice of sustainable development.

It is easy to be sceptical about the future prospects for sustainable development. Its aim of finding ways of balancing human activity with sustaining natural ecosystems may appear impossibly utopian. Nonetheless, sustainable development looks to create common ground among nation-states and connects the world development movement with the environmental movement in a way that no other project has yet managed to do. It gives radical environmentalists the opportunity to push for full implementation of its widest goals, but, at the same time, moderate campaigners can be involved locally and exert some influence. A more technology-focused approach, which may be seen as close to the sustainable development project, is known as ecological modernization, and we introduce this in the next section.

Sustainable development is ‘development which meets the needs of the present generation, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ How could we find out what the needs of future generations will be? Can sustainable development policies be devised from this definition?

For environmentalists, both capitalist and communist forms of modernization have failed. They have delivered wealth and material success, but at the price of massive environmental damage. In recent years, groups of academic social scientists in Western Europe have developed a theoretical perspective called ecological modernization (EMT), which accepts that ‘business as usual’ is no longer possible but also rejects radical environmentalist solutions involving de-industrialization. Instead they focus on technological innovation and the use of market mechanisms to bring about positive outcomes, transforming production methods and reducing pollution at its source.

EMT sees huge potential in the leading European industries to reduce the use of natural resources without this affecting economic growth. This is an unusual position, but it does have a certain logic. Rather than simply rejecting economic growth, proponents argue that an ecological form of growth is theoretically possible. An example is the introduction of catalytic converters and emission controls on motor vehicles, which has been delivered within a short period of time and shows that advanced technologies can make a big difference to greenhouse gas emissions. If environmental protection really can be achieved this way, especially in renewable energy generation and transport, then we can continue to enjoy our high-technology lifestyles.

Ecological modernizers also argue that, if consumers demand environmentally sound production methods and products, market mechanisms will be forced to try and deliver them. Opposition to GM food in Europe (discussed above) is a good example of this idea in practice. Supermarkets have not stocked or pushed the supply of GM foods, because large numbers of consumers have made it clear that they will stay on the shelves.

The theory of ecological modernization sees that five social and institutional structures need to be ecologically transformed:

1 science and technology: to work towards the invention and delivery of sustainable technologies

2 markets and economic agents: to introduce incentives for environmentally benign outcomes

3 nation-states: to shape market conditions which allow this to happen

4 social movements: to put pressure on business and the state to continue moving in an ecological direction

5 ecological ideologies: to assist in persuading more people to get involved in the ecological modernization of society (Mol and Sonnenfeld 2000).

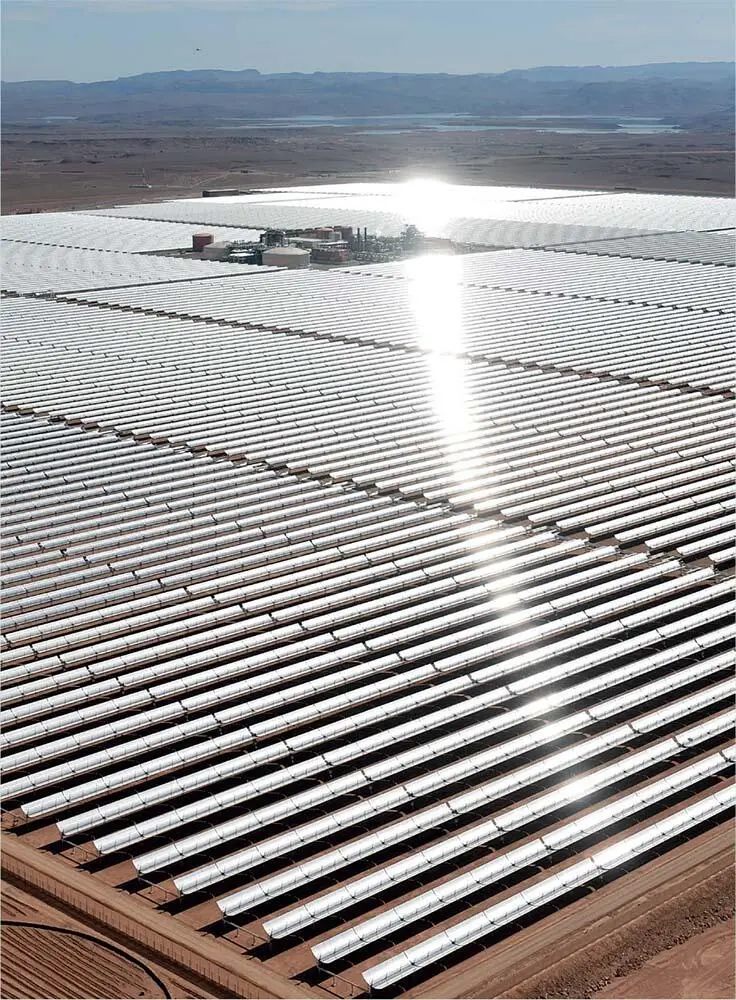

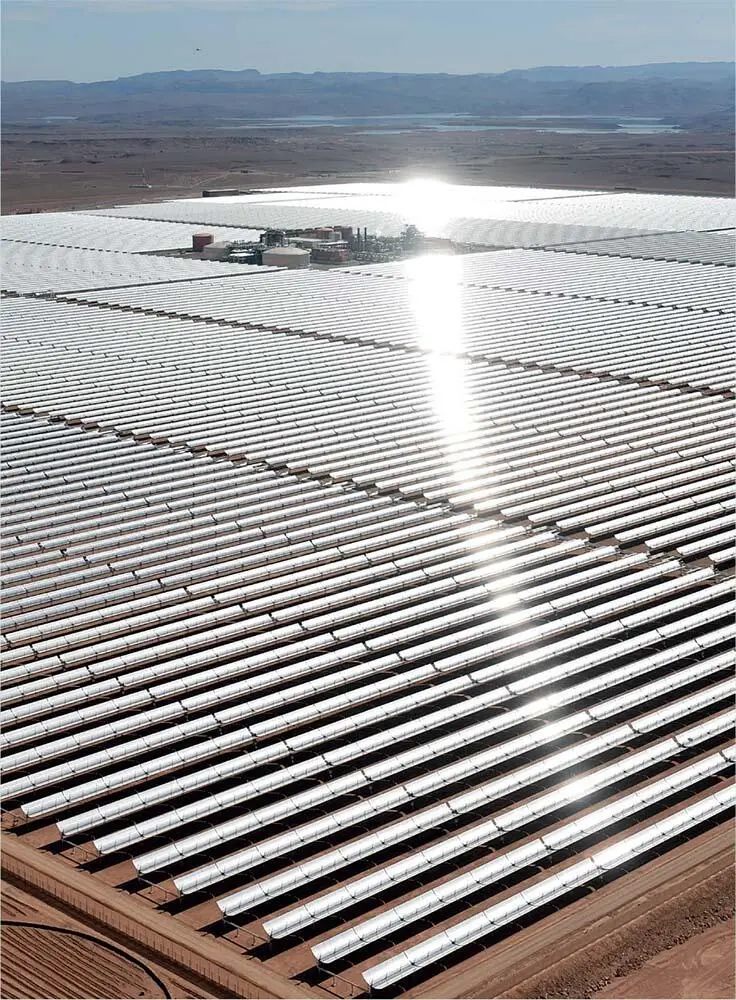

Global society 5.3 Solar power: ecological modernization in practice?

A key plank of the ecological modernization perspective is that non-polluting technologies, such as renewable energy projects, can make a big impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Renewable technologies can also be made available to developing countries to help them avoid the high-polluting forms of industrialization which have caused so much environmental degradation.

One widely reported recent example is the massive solar power plant (actually four linked sites) being constructed in Ouarzazate, Morocco, which could supply the energy needs of 1 million people. This is crucial to the country’s ambitious target of generating over 40 per cent of its electricity from renewables – a huge change given its previously heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels such as coal and gas. The technologically innovative aspect of the plant is not just its size – the many rows of solar mirrors cover an area as large as thirty-five football pitches or the size of the capital city, Rabat – but also its attempt to store the energy generated from the sun using salt.

The plant generates heat that melts the salt, which is then able to store the heat, which in turn generates enough steam to power turbines overnight. Morocco’s hot desert climate is a necessary environment for such a scheme. The solar mirrors are more expensive to produce than conventional photovoltaic panels, but the big advantage is that they continue generating power even after sundown. The storage system promises to hold energy for up to eight hours, meaning that a continuous solar energy supply should be possible.

When the plant is completed, the hope is that enough energy will be generated to allow Morocco to export some of it to Europe. The project is a public–private partnership and will cost around $9 billion, much of which is from the World Bank and other private and public financial institutions. But, if it fulfils its promises, the Noor Ouarzazate complex may be one of the most striking and successful practical examples of ecological modernization yet seen.

Sources : World Bank (2015); Harrabin (2015); Neslen (2015).

Science and technology have a particularly crucial role in developing preventative solutions, building in ecological considerations at the design stage. This will transform currently polluting production systems.

Since the mid-1990s, three new areas of debate have entered the ecological modernization perspective. First, research began to expand to the developing countries, significantly challenging the Eurocentrism of the original perspective. Second, once ecological modernizers started to think beyond the West, the theory of globalization became more relevant (Mol 2001). Third, ecological modernization has started to take account of the sociology of consumption and theories of consumer societies. These studies look at how consumers can play a part in the ecological modernization of society and how domestic technologies can be improved to reduce energy consumption, save scarce resources (such as water) and contribute to waste reduction through recycling.

Читать дальше