Merton saw that many sociological studies focused on either the macro level of society or the micro level of social interaction but failed to ‘fill in the gaps’ between macro and micro. To rectify this, he argued for middle-range theories of the meso level in particular areas or on specific subjects. An excellent example is his study of working-class criminality and deviance. Why was there so much acquisitive crime among the working classes? Merton’s explanation was that, in an American society which promotes the cultural goal of material success but offers very few legitimate opportunities for lower social class groups, working-class criminality represented an adaptation to the circumstances in which many young people found themselves. The fact that they aimed to achieve the material success promoted by the system meant they were not evil or incapable of reform. Rather, it was the structure of society that needed to change. This thesis shows that Merton tried to develop functionalism in new directions, and, in doing so, he moved closer to conflict theory.

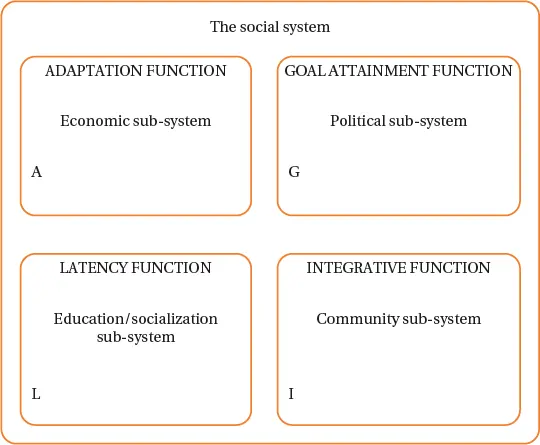

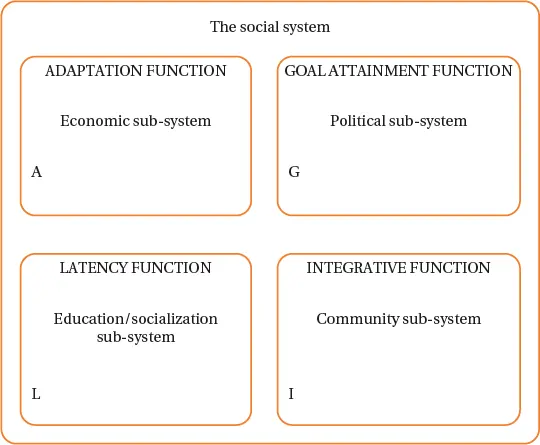

Figure 3.1 Parsons’s AGIL scheme

Merton also distinguished between manifest and latent functions: the former are observable consequences of action, the latter are those that remain unspoken. In studying latent functions, Merton argued, we can learn much more about the way that societies work. For example, we might observe a rain dance among tribal people, the manifest function of which appears to be to bring about rain. But, empirically, the rain dance often fails and yet continues to be practised – why? Merton argues that its latent function is to build and sustain group solidarity, which is a continuing requirement. Similarly, Merton argued that institutions contained certain dysfunctional elements which create tensions, and the existence of these allowed him to discuss the potential for conflict in ways that Parsons could not.

See chapter 22, ‘Crime and Deviance’, for a more detailed discussion and critique of Merton’s ideas.

What became of structural functionalism? Following the death of Parsons in 1979, Jeffrey Alexander (1985) sought to revisit and revive the approach, aiming to tackle its theoretical flaws. But, by 1997, even Alexander was forced to concede that the ‘internal contradictions’ of his ‘new’ or neofunctionalism could not be resolved. Instead, he argued for a reconstruction of sociological theory beyond functionalist assumptions (Alexander 1997). Hence, Parsonian structural functionalism is, to all intents and purposes, defunct within mainstream sociology.

Parsons’s ideas became so influential because they spoke to the developed societies about their post-1945 situation of gradually rising affluence and political consensus. But they lost ground in the late 1960s and the 1970s as conflicts began to mount, with new peace and anti-nuclear movements, protests against American military involvement in Vietnam, and radical student movements emerging in Europe and North America. At that point, conflict theories, such as Marxism, were reinvigorated, as they offered a better understanding of the new situation. As we will see later, understanding globalization, multiculturalism, shifting gender relations, risk and environmental degradation has led to a new round of theorizing today.

Merton sought to explain why a disproportionate amount of officially recorded acquisitive crime involved the working classes.

Max Weber: capitalism and religion

The third of the traditionally cited ‘founding fathers’ of European sociology, alongside Marx and Durkheim, is Max Weber, whose ideas stand behind many actor-centred approaches. His most famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1992 [1904–5]), tackled a fundamental problem: why did capitalism originate in the West? For around thirteen centuries after the fall of ancient Rome, other civilizations were more prominent than those in the West. In fact, Europe was a rather insignificant part of the world, while China, India and the Ottoman Empire in the Near East were all major powers. China in particular was a long way ahead of the West in its level of technological and economic development. So how did Europe’s economies become so dynamic?

Weber reasoned that the key is to show what makes modern capitalism different from earlier types of economic activity. The desire to accumulate wealth can be found in many historical civilizations, and people have valued wealth for the comfort, security, power and enjoyment it can bring. Contrary to popular belief, capitalist economies are not simply a natural outgrowth of the desire for personal wealth. Something different must be at work.

Religion in the heart of capitalism?

Weber argued that, in the economic development of the West, the key difference is an attitude towards the accumulation of wealth that is found nowhere else in history. He called this attitude the ‘spirit of capitalism’ – a motivating set of beliefs and values held by the first capitalist merchants and industrialists. Yet, quite unlike wealthy people elsewhere, these industrialists did not spend their accumulated riches on luxurious, materialistic lifestyles. On the contrary, many of them were frugal and self-denying, living soberly without the trappings of affluence we are used to seeing today. This very unusual combination was vital to the rapid economic development of the West. The early capitalists reinvested their wealth to promote further expansion of their enterprises, and this continual reinvestment of profits produced a cycle of investment, production, profit and reinvestment, allowing capitalism to expand quickly.

The controversial part of Weber’s theory is that the ‘spirit of capitalism’ actually had its origins in religion. The essential motivating force was provided by the impact of Protestantism and one variety in particular: Puritanism. The early capitalists were mostly Puritans and many subscribed to Calvinism. Calvinists believed that human beings are God’s instruments on Earth, required by the Almighty to work in a vocation – an occupation for the greater glory of God. They also believed in predestination, according to which only certain individuals are among the ‘elect’ and will enter heaven in the afterlife. In Calvin’s original doctrine, nothing a person does on Earth can alter whether they are one of the elect; this is predetermined by God. However, this belief was difficult to live with and produced much anxiety among followers, leading to a constant search for ‘signs’ of election to quell salvation anxiety.

People’s success when working in a vocation, indicated by their increasing prosperity, came to be seen as a sign that they were part of the elect few. Thus, a motivation towards profitability was generated as an unintended consequence of religious adherence, producing a paradoxical outcome. Puritans believed luxury to be evil, so their drive to accumulate wealth was combined with severe and unadorned personal lifestyles. This means the early capitalists were not self-conscious revolutionaries and did not set out to produce a capitalist revolution. Today, the idea of working in a calling has faded, and successful entrepreneurs have stupendous quantities of material goods and live luxurious lifestyles. In a famous passage, Weber (1992 [1904–5]: 182) says:

Читать дальше