Sociologists’ views differ on the value of biographical methods. Some feel they are too unreliable and subjective to provide useful information, but others see that they offer sources of insight that few other research methods can match. Indeed, some sociologists have begun to offer reflections on their own lives within their research studies as a way of offering insights into the origins and development of their own theoretical assumptions (see, for example, Mouzelis 1995).

Comparative and historical research

Comparative research is of central importance in sociology, because making comparisons allows us to clarify what is going on in a particular area of social life. Take the rate of divorce among opposite-sex couples in many developed societies as an example. In the early 1960s there were fewer than 30,000 divorces per year in England and Wales, but by 2003 this figure had risen to 153,000. However, since 2003 the annual number of divorces has been falling, and in 2017 it stood at 101,669. The divorce rate also fell, to 8.4 divorcing persons per 1,000 married population, the lowest level since 1973 (ONS 2018a). Do these changes reflect specific features of British society? We can find out by comparing divorce rates in the UK with those of other countries. Comparison with figures for other Western societies reveals that the overall trends are in fact quite similar. A majority of Western countries experienced steadily climbing divorce rates over the latter part of the twentieth century, which appear to have peaked early in the twenty-first century before stabilizing or falling back in recent years. What we may conclude is that the statistics for England and Wales are part of a broader trend or pattern across modernized Western societies.

Classic studies 2.1 The social psychology of prison life

The research problem

Most people have not experienced life in prison and find it hard to imagine how they would cope ‘inside’. How would you fare? What kind of prison officer would you be – a disciplinarian maybe? Or perhaps you would adopt a more humanitarian approach to your prisoners? In 1971, a research team led by Philip Zimbardo decided to try and find out what impact the prison environment would have on ‘ordinary people’.

In a study funded by the US Navy, Zimbardo set out to test the ‘dispositional hypothesis’, which dominated within the armed forces. This hypothesis suggested that constant conflicts between prisoners and guards were a result of the conflicting individual characters of the guards and inmates – their personal dispositions. Zimbardo thought this might be wrong and set up an experimental prison to find out.

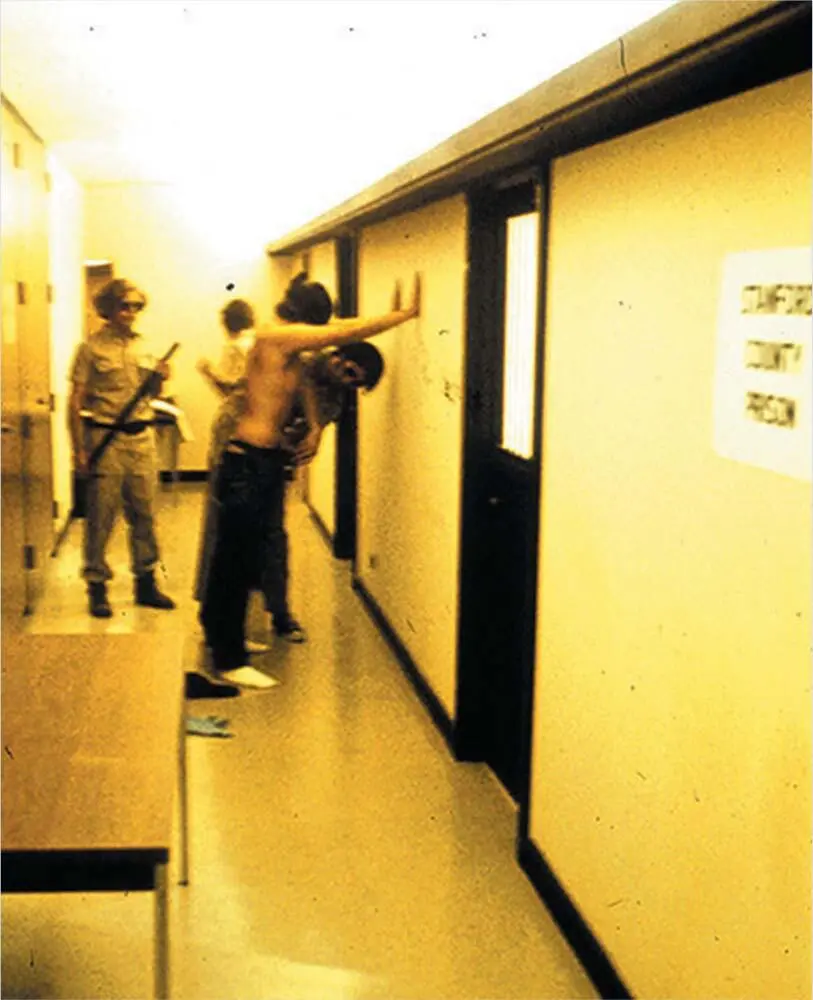

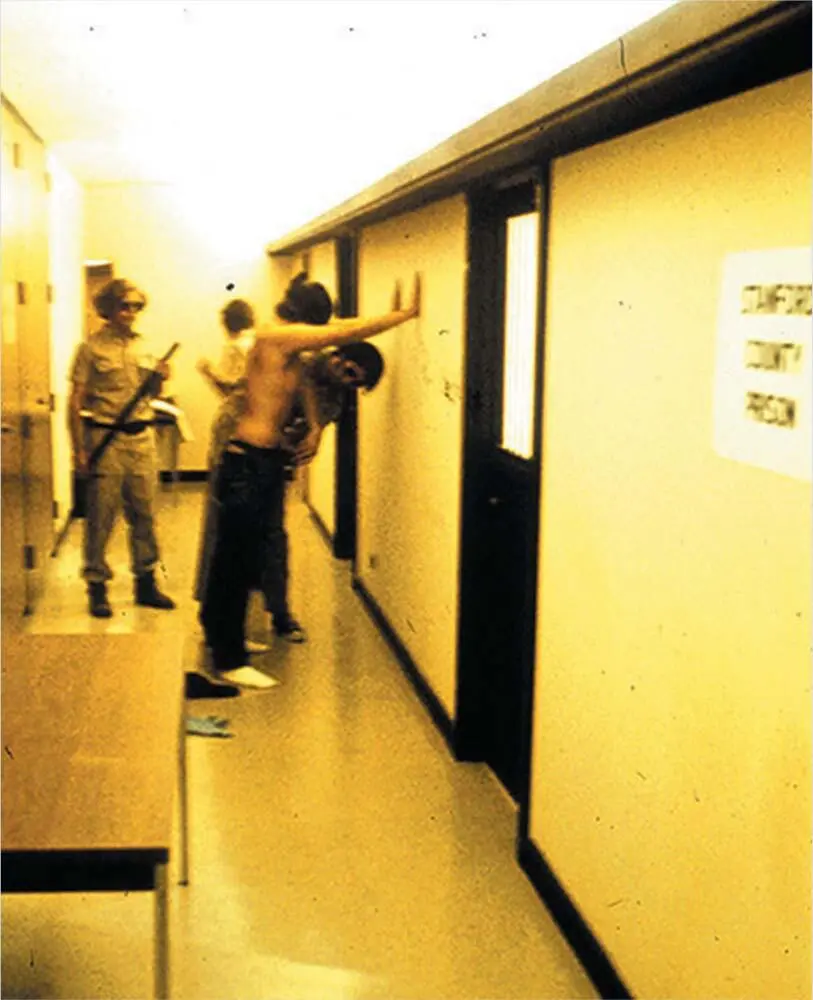

Zimbardo’s research team set up an imitation jail at Stanford University, advertised for male volunteers to participate in a study of prison life, and selected twenty-four mainly middle-class students who did not know one another. Each participant was randomly assigned a role as either a guard or a prisoner. Following a standard induction process, which involved being stripped, de-loused and photographed naked, prisoners stayed in jail for twenty-four hours a day, but the guards worked shifts and went home afterwards. Standardized uniforms were used for both roles (Haney et al. 1973). The aim was to see how playing the different roles would lead to changes in attitude and behaviour. What followed shocked the investigators.

Students who played the part of guards quickly assumed an authoritarian manner, displaying real hostility towards prisoners, ordering them around, verbally abusing and bullying them. The prisoners, by contrast, showed a mixture of apathy and rebelliousness – responses often noted among inmates in studies of real prisons. These effects were so marked and the level of tension so high that the fourteen-day experiment had to be called off after just six days because of the distress exhibited by participants. Even before this, five ‘prisoners’ were released because of extreme anxiety and emotional problems. However, many ‘guards’ were unhappy that the study had ended prematurely, suggesting they enjoyed the power the experiment afforded them.

Reactions to the mock prison regime in the Stanford prison experiment led one inmate to stage a hunger strike just to get out.

On the basis of the findings, Zimbardo concluded that the dispositional hypothesis could not account for the participants’ reactions. Instead, he proposed an alternative ‘situational’ explanation: behaviour in prisons is influenced by the prison situation itself, not by the individual characteristics of those involved. In particular, the expectations attached to the roles being played tended to shape people’s behaviour. Some of the guards’ behaviour had deteriorated – they treated prisoners badly, regularly handing out punishments and appearing to take pleasure in the distress of the prisoners. Zimbardo suggested this was due to the power relationships the jail had established. Their control over prisoners’ lives very quickly became a source of enjoyment for the guards. On the other hand, following a short period of rebelliousness, prisoners exhibited a ‘learned helplessness’ and dependency. The study tells us something important about why social relationships often deteriorate within prisons and, by implication, in other ‘total institutions’ (Goffman 1968 [1961]). This has little to do with individual personalities and much more to do with the social structure of the prison environment and the social roles within it.

Critical points

Critics argue that there were serious ethical problems with this study. Participants were not given full information about the purpose of the research, and it is questionable whether they could really have given ‘informed consent’. Should the study even have been allowed to go ahead? The sample selected was clearly not representative of the population as a whole, as all were students and all were male. Generalizing about the effects of ‘prison life’ is therefore very difficult based on such a small and unrepresentative sample. The constructed nature of the situation may also invalidate the findings for generalizing to real-world prison regimes. For example, participants knew their imprisonment would last only fourteen days, and they were paid $15 a day for their participation. Well-established problems of prisons such as racism, violence and sexual abuse were also absent. Critics say that the experiment is therefore not a meaningful comparison with real prison life.

Contemporary significance

In spite of the somewhat artificial situation – it was an experiment, after all – Zimbardo’s findings have been widely referred to since the 1970s. For example, Zygmunt Bauman’s Modernity and the Holocaust (1989) draws on this study to help explain the behaviour of inmates and guards in Nazi-run concentration camps during the Second World War. In recent years the issue of mistreatment and bullying of older and disabled people in care-home settings in England has been exposed in a series of scandals, resulting in dismissals and the prosecution of staff members. Zimbardo (2008) himself discussed some of the parallels between the experiment and real-world episodes, including the abuse and torture of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib in 2003–4, suggesting that the focus should be not on finding the ‘bad apple’ but on reforming the ‘bad barrel’. His most general thesis, that institutional settings can shape social relations and behaviour, remains a powerful one.

Читать дальше