The researcher must then decide just how the research materials are to be collected. A range of different research methods exists, and which one is chosen depends on the overall objective of the study, as well as on which aspects of behaviour are to be analysed. For some purposes, a social survey (in which questionnaires are normally used) might be suitable, especially where we need to gather a large quantity of data. In other circumstances, if we want to study small social groups in great detail, interviews or an observational study might be more appropriate. We shall learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter.

At the point of proceeding with the research, unforeseen practical difficulties can crop up, and very often do. For example, it might prove impossible to contact some of those to whom questionnaires are to be sent or those people the researcher wishes to interview. A business firm or school may be unwilling to let the researcher carry out the work they had planned due to concerns about sensitive information being leaked. Difficulties such as this could result in bias, as the researcher may be able to gain access only to a partial sample, which subsequently leads to a false overall result. For example, if the researcher is studying how business corporations have complied with equal opportunities programmes for disabled people, companies that have not complied may not want to be studied, but omitting them will result in a systematic bias in the study’s findings.

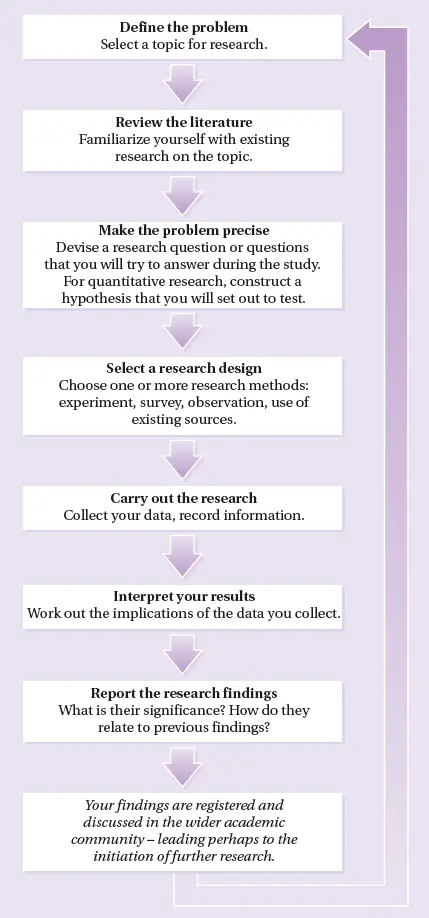

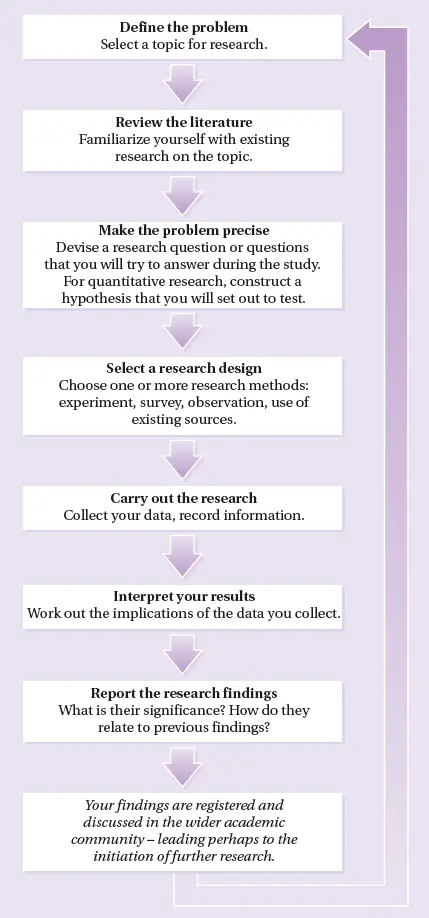

Figure 2.1 Steps in the research process

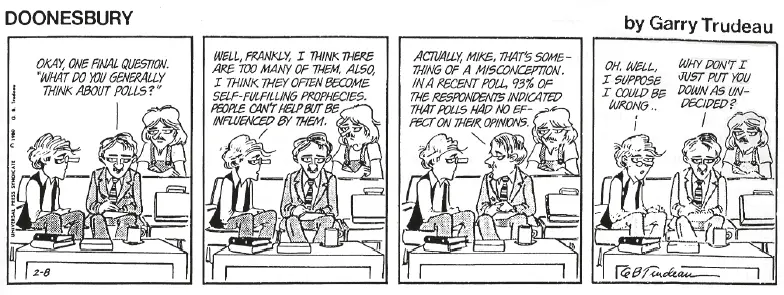

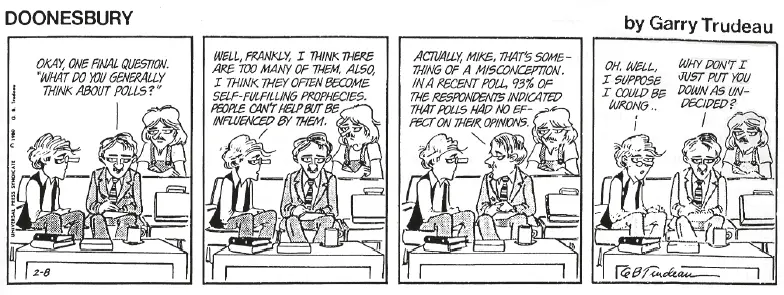

Bias can enter the research process in other ways too. For example, if a study is based on a survey of participants’ views, the researcher may, even unwittingly, push the discussion in a particular direction, asking leading questions that follow their own viewpoint (as the Doonesbury cartoon shows). Alternatively, interviewees may evade a question that they just do not want to answer. The use of questionnaires with fixed wording can help to reduce interview bias, but it will not eliminate it entirely. Another source of bias occurs when potential participants in a survey, such as a distributed voluntary questionnaire, decide that they do not want to take part. This is known as non-response bias , and, as a general rule, the higher the proportion of non-responses in the sample, the more likely it is that the survey of those who do take part will be skewed. Even if every attempt is made to reduce bias in surveys, the observations that sociologists make in carrying out a piece of research are likely to reflect their own cultural assumptions. This observer bias can be difficult and perhaps even impossible to eliminate, as sociologists – believe it or not – are human beings and members of societies as well as sociologists! Later in this chapter we look at some of the other pitfalls and difficulties of sociological research and discuss how these can be avoided.

Interpreting and reporting the findings

Once the material has been gathered together for analysis, the researcher’s troubles are not over. Working out the implications of the data and relating these back to the research problem are rarely easy. While it may be possible to reach a clear answer to the initial questions, many investigations are, in the end, less than fully conclusive. The research findings, usually published in a report, journal article or book, provide an account of the nature of the research and seek to justify whatever conclusions are drawn. This is a final stage only in terms of the individual project. Most reports also indicate questions that remain unanswered and suggest further research that might profitably be done in the future. All individual investigations are part of the continuing process of research which takes place within the international sociological community.

The preceding sequence of steps is a simplified version of what happens in actual research projects (see figure 2.1). In real-world research, these stages rarely succeed each other so neatly and there is almost always a certain amount of ‘muddling through’. The difference is a bit like that between following a recipe in a cookbook and the actual process of cooking a meal. People who are experienced cooks often do not work from recipes at all, yet their food may be better than that cooked by those who do. As Feyerabend saw, following a rigid set of stages can be unduly restrictive, and many outstanding pieces of sociological research have not followed this strict sequence. Still, most of the steps discussed above would be in there somewhere.

Understanding cause and effect

One of the main problems to be tackled in research methods is the analysis of cause and effect, especially in quantitative research which is based on statistical testing. A causal relationship between two events or situations is an association in which one event or situation produces another. If the handbrake is released in a car that is parked on a hill, the car will roll down the incline, gathering speed progressively as it does so. Taking the brake off was the immediate cause of this event, and the reasons for it can readily be understood by reference to the physical principles involved. Like natural science, sociology depends on the assumption that all events have causes. Social life is not a random array of occurrences. One of the main tasks of sociological research and theorizing is to identify causes and effects.

Causation and correlation

Causation cannot be directly inferred from correlation. Correlation means the existence of a regular relationship between two sets of occurrences or variables. A variable is any dimension along which individuals or groups vary. Age, gender, ethnicity, income and social class position are among the many variables that sociologists study. It might seem, when two variables are found to be closely linked, or correlated, that one must be the cause of the other. Yet this is very often not the case. Many correlations exist without any corresponding causal relationship between the variables involved. For example, over the period since the Second World War, a strong correlation can be found between the decline in pipe-smoking and the decrease in the number of people who regularly go to the cinema. Clearly one change does not cause the other, and we would find it difficult to discover even a remote causal connection between them. There are other instances in which it is not quite so obvious that an observed correlation does not imply a causal relationship. Such correlations are traps for the unwary and easily lead to questionable or false conclusions.

In his classic work of 1897, Suicide (discussed in chapter 1), Emile Durkheim found a correlation between rates of suicide and the seasons of the year. Levels of suicide increased progressively from January to around June or July and then declined over the remainder of the year. It might be supposed that temperature or climatic change is causally related to the propensity of individuals to commit suicide. We might surmise that, as temperatures increase, people become more impulsive and hot-headed, leading to higher suicide rates. However, the causal relationship here has nothing to do directly with temperature or climate at all. In spring and summer, most people engage in a more intensive social life than they do in the winter months. Those who are isolated or unhappy tend to experience an intensification of these feelings as the activity level of other people around them rises. Hence they are likely to experience acute suicidal tendencies more in the spring and summer than they do in autumn and winter, when the pace of social activity slackens. We always have to be on our guard, both in assessing whether correlation involves causation and in deciding in which direction causal relations run.

Читать дальше