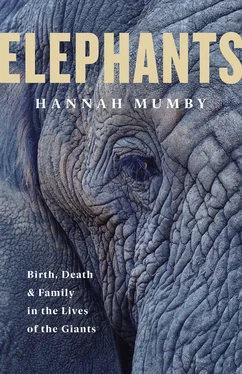

It wasn’t inevitable that my life would end up this way, defined by elephants: their lives, their movements, their habits and the similarities and differences between us and them. I didn’t grow up in the bush like Ronny. I’m not South African like him and Jess. If you’d asked me when I was seven what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d have said Indiana Jones or David Attenborough. But these early field-based dreams drifted away as I was increasingly buried in academic literature, revision and exams. I feel as though I came to from my teenage years as an undergraduate student at King’s College, Cambridge: slightly baffled as to how as a first generation university student I managed to end up there, but equally determined that I had been very sure it was where I should be. I was overwhelmed by the looming architecture, at once oppressively cloistered and staggeringly grand. It echoed my inability to engage with both the nuanced and visually spectacular traditions, acted out by others with an ease and naturalness I couldn’t hope to emulate. I was equally intimidated by the wider features of the student experience. I didn’t row in one of the college boats, I didn’t act or write for the newspaper, I didn’t get a glitzy internship. I sat in the library, shell-shocked by how very little I knew and could ever hope to know.

Feeling adrift, I needed a framework to understand myself, as an individual and as a human being. I decided the solution to understanding my place in the world was to get to the bottom of what it means to be human. Unsurprisingly, even this task was a little over-ambitious for my undergraduate dissertation. Then, in a second-year lecture, my Cambridge experience turned around dramatically. I found the ideas of life history, and, with it, an elegant clarity that comes with the most beautifully constructed scientific theories. At its core, the theory is about explaining how living organisms balance energy and time in their development, reproduction and senescence.

For me, it was about understanding any living organism by getting to the nuts and bolts of how it is born or comes to being, grows, reproduces (or not) and dies. These are universal traits that bind us living things together, but we experience them as individuals. This means we can observe enormous variation both between organisms and between lives; for example, the overall picture is that humans are long-lived animals with slow-paced lives, but this masks the fact that some of us live a few minutes or hours and others live for over a century. How do these patterns of mortality put pressure on the shape of our lives as a species? It was the perfect lens through which to see myself and the world. It allowed me to put aside the idea of humans as exceptional and use the principles to understand my own life as just another creature.

With this in mind, I started studying the lives of primates. Non-human primates like monkeys, apes and lemurs are the go-to comparative organisms for humans. This makes complete sense on one level, because they are our closest relatives. I launched myself into conducting an ambitious study for my undergraduate dissertation. I was trying to use a life-history formula to determine whether the pace of human life was typical of a primate, or if it was an outlier, standing out from the usual pattern. What I mean by the pace of life isn’t just the lifespan. I mean whether key ‘milestones’ in our life history, such as weaning and age at first reproduction, are very spread out, or if they are clumped together. It’s often useful to view life histories as on a continuum. For example, in mammals it could go from a ‘fast-living’ creature like a mouse, which matures rapidly, has many offspring and a relatively short life, to animals that have a longer development, space out their offspring more and have a longer life, like humans. All of this can be influenced by body size: large bodies take longer to grow, so we have to take this into account. Without celebrating myself too much, I was excited to discover that although humans are living in the slow lane even among primates, we humans aren’t an absolute outlier. We aren’t even the slowest of the species I researched.

I felt thrilled with my contribution to scientific knowledge, and the head of the Anthropology Department recommended that I publish it. I felt accepted and valued in a way that I hadn’t in several years of port and cheese parties (although I had managed to develop a taste for port and a fear it would give me gout, and a particular joy in truffled pecorino). Then, I thought more about it, and more, and then just too much. I realised how limited my study really was. I had a horrible, sinking realisation that I was effectively standing with my nose a couple of inches from a pointillist painting and happily telling everyone I could see the big picture. I could in fact just see some lovely green dots, but I could definitely not see a picnic scene by the River Seine (or whatever your favourite pointillist scene depicts).

At the time, I was working on an alumni database at a Cambridge college. Twiddling my thumbs, romanticising about becoming an academic, but not ready to inhabit that life. I began to unpick my failure and re-evaluate my approach. Really, I had put humans into their primate context, but humans aren’t just primates. And how much do we have in common with more distantly related primates like lemurs? What I needed to do was forget about relatedness and just look for the slow life-history pattern across animals. If I could find an animal that had evolved on a separate trajectory and wasn’t related to humans, it would be all the more interesting. I could investigate the similarities and differences between lives without having to worry that I was just describing the general primate pattern. I started a list. I wrote down ‘whales’. I grimaced at the thought of seasickness and crossed it out. I wrote down ‘elephants’, and changed the direction of my life.

A few months later I arrived in Kenya. I had never been on a flight with request stops before, never mind on such a tiny plane. A stroke of luck meant that the former master of the college where I had been working had been an influential elephant researcher in the 1960s and 1970s and had recommended I seek out a PhD student he had examined. The PhD student was Iain Douglas-Hamilton, who had become a giant of elephant research. Before I had even met Iain, I had been told he was an ‘elephant’. I knew by reputation that he was superlatively intelligent, incredibly productive and passionately committed to his work. But I thought that being an elephant sounded mad. I had heard about him being chased around a thorny bush by a female elephant and being lucky that he had only ended up with a few scratches. The real mystery, he told me, was her intention. ‘Did she actually intend to kill me, when she overran me and plunged her tusks nine inches into the ground above my head? Did she change her mind after I was under her, at her mercy, or was it only her intention from the start to frighten me? Either way, she was certainly successful in increasing my heartbeat!’

Despite these fortuitous connections, Kenya was more alien than Cambridge had ever been. When we landed in Samburu I was in equal parts happy I was alive and proud I had kept down my breakfast, particularly because one of the younger passengers had not managed the latter. I hauled my backpack off the plane and dragged it through the sand to the edge of the runway. I glanced at the rickety table of knick-knacks bearing a ‘duty-free’ sign, unsure as to whether it was a spirited attempt at a shop or a joke. The airstrip was deserted. I sat on my backpack and wished I had water. The sun was getting higher in the sky and I squinted. I thought I should have reminded someone I was coming here. Could it be they didn’t know, and I was going to have to get back on that terrifying little plane? Luckily, my anxious musings were broken by two men asking where I was staying.

Читать дальше