There was a time when I thought a great deal about the axolotls. I went to see them in the aquarium at the Jardin des Plantes and stayed for hours watching them, observing their immobility, their faint movements. Now I am an axolotl.

Julio Cortázar

‘I can’t hear anything.’

‘Nothing at all?’

‘Honestly, just feedback, wasn’t his last point here?’

‘Oh, but that point was very early this morning. Let’s look for him.’

I sighed and took the radio receiver from my ear. I was tracking a male elephant named Bulumko up in the very north-eastern corner of South Africa with Ronny and Jess, two experienced field workers. I had expected to hear a clear and firm ‘bleep, bleep’ from the tracking collar which Bulumko had been wearing for several years now. The collar communicated with a satellite, so we could know Bulumko’s movements from afar, and usually with the antenna that I was holding up in the air. But not today. Instead, there was no trace of him, just a tantalisingly close GPS point we’d received several hours ago when he was foraging nearby. I felt mildly exasperated that the technology had let me down. Or perhaps it was just that I hadn’t downed enough tea and rusks since we’d set off at daybreak.

Ronny was already scanning the horizon from the canvas roof of our beautiful new vivid green pickup truck, lovingly known to the Elephants Alive employees as Shrek. After tracking elephants from an enclosed bakkie 4x4, an off-roading vehicle, we now had the freedom, luxury and coolness of an open vehicle. It was almost autumn, but the daytime temperatures could still soar up to 34 degrees, and Shrek was the best place to be if you couldn’t make it to a swimming pool. I clambered up to join Ronny and then jumped back down to get my binoculars, remembering the gulf between my eyesight and his.

Up on the roof, my hunger and frustration slipped away as I felt the precious light breeze fluttering my untucked shirt. I could hear melodious bird calls and buzzing flies attracted to our sweat. After a second, I started to become aware of the landscape. This place could seem vast and monotonous. But after a few visits I had started to pick up on the variation – in parts it was an immense and undulating expanse of flat-leafed mopane trees, joining into a blanket; in others it was more open savannah punctuated with termite mounds, spiky barked knobthorn trees and the broad-canopied and fragrant marula. I happily noted the subtle gradient in vegetation along the slopes and riversides. It shifted with the seasons too. We’d had a little more rain this year, and there was a layer of green underneath the trees. Not thick, or deep, but somehow speaking of life and its persistence in a place that could be so harsh and arid. I thought of last year, of the blistered, sunburned hippos wallowing ankle-deep in what should have been pools and shook my head to rid myself of the memory.

Ronny’s eyes were fixed in the distance. He knew how to track elephants and other animals, so I knew to take my cues from him. He grew up at a nearby safari lodge, where his mum worked in housekeeping, and his uncle was a tracker. Today we were searching for tell-tale signs of elephants: movement in the trees on the horizon or the sound of breaking branches. I could complain about the flashy technology letting us down, but this was really the way to find elephants. You got more of a sense of scale, of how they fitted into the picture; to rely on your senses and be aware of the bush, the sun, and of yourself within it all. Having said that, I’d made plenty of phantom elephant sightings, mistaking rocks, tree trunks or buffalo for one of our big grey study animals. Today, we were going to get the real thing.

Suddenly, Ronny smiled. ‘There he is! In that big block of trees!’

I held up the binoculars to my myopic eyes, a result of too many hours looking at screens and books close-up and not enough out here. Of course, Ronny was right. Bulumko. He was a towering and impressive bull in his prime. He was old enough to have distinctive notches in his ears. He probably caught them on branches or thorns, and elephants tend to have more ragged ears the older they get. We used them to confirm his identity. He’d also grown a pair of jutting tusks, by no means the biggest I had seen, but each over a metre long. He had been tracked for years by Elephants Alive; and knowing the elephants as individuals with their own lives and experiences over time was what attracted me to them in the first place. What’s more, the elephants had names, not just numbers. Bulumko’s name meant wisdom, but what always struck me was the way he moved. He ambled, feeling the trees with his trunk and taking time to determine his route. He favoured travelling along the dirt roads that we drove along in our vehicle, and he occasionally lingered by water sources longer than the other males. Like every elephant I had ever known, Bulumko had his quirks and unique features. But he was a little different even beyond that. Bulumko was blind.

In many species, a blind individual just wouldn’t survive. But sight isn’t as important for elephants as it is for other animals. Hearing and smell are much more critical. Bulumko has not just found a way to navigate the world without his sight, he’d also found a way to navigate social life. He could displace other males for access to the freshest water or a prime shady spot to rest in. Even if he wasn’t receiving direct care from other animals, he was certainly accepted and even dominant because of his stature, age and tusks. Our relationship with Bulumko was singular, because while the other elephants we watched became habituated to our presence, Bulumko accepted us as friends and co-travellers. We could stay with him for hours by a waterhole as he bathed and we enviously sweated in the sun. When he moved off, he rumbled, a short but low and sonorous sound indicating to us to follow – let’s go! I often wondered whether Bulumko was more likely than other elephants to communicate with us in this way precisely because of his blindness. With him, we were beyond being observers, we were almost another elephant. Perhaps not seeing us made it easier for him to interact with us as companions, and our car was like another big animal. Except it smelt of people and talked like us too.

Excited to ‘talk’ to Bulumko again and, of course, to listen, I clambered down off the roof, eager to drive to a spot where we could get a better sighting of him. I smiled at Ronny and Jess. ‘This is the life!’ Jess laughed and shook her head at me. But it really was what I wanted, to be treated like an elephant by an elephant. Then Jess revved Shrek’s heavy engine and we drove to Bulumko, leaving a trail of dust in our wake.

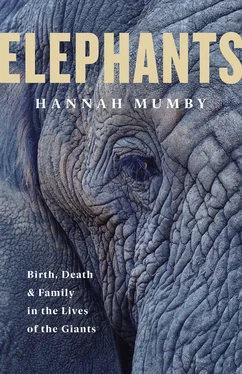

What is an elephant? A favourite character in a childhood book, a weapon of war, a religious icon, a draught animal, a pest, a conservation flagship, a source of income, a drain on income, a hunting prize, a tourist trap, a terrifying beast, a gentle giant, a source of ivory or a source of power. It has at one time or another been all of these, and the diversity of responses illustrates the complexity and history of our relationship with our world’s biggest land mammals. Few animals evoke such heartfelt passion and division of opinion. It often strikes me that these enormous animals carry with them so much meaning, symbolism and sometimes baggage, but at least they have the strength for it. Many scientists have to carefully introduce and describe their study species of cichlid fishes, fruit flies, honeyguides or sticklebacks. When I say that I work with elephants, most people already have a firm image in their minds, which can be hard for me to compete with. But the way I see elephants is as personal as it is for everyone else. For me, elephants are the biggest, most complex and endlessly fascinating puzzle I have ever faced. And I’ve done one of those thousand-piece jigsaws. How elephants can make evolutionary sense with their long lives, inefficient guts and slow reproduction in a world where being small, reproducing fast and multiplying exponentially is an option continues to intrigue me. How do we have giants in this world? And how do we live with them?

Читать дальше