Urban planning thought and practice have long been exchanged. City plans have been copied, ideas for unrealized cities have provided inspiration, and particular policies or techniques of planning have been adopted widely. To add to this, apparently similar urban forms and principles of urban planning have developed in synchrony in different parts of the world. What are we to make of this? To me, this signals the power of the urban planning imagination. Urban planning has appeal because it is needed. It has seduced and continues to seduce. How we reflect on and mobilize this power will be important to urban planning in an urban age.

I conclude in chapter 8by considering the future of urban planning in the present age. This is a future of the mixing of actors, the knowledge and wisdom they bring to substantive challenges, and the methods they make use of when drawing from historical and geographical vantage points. It will need to be a progressive mix with purpose rather than one that produces lowest-common-denominator outcomes, an incompatible pick and mix, or partial and exclusive combinations of citizen, club and state urban planning imaginaries.

1 1 Much of the critique of modern urban planning as everything and nothing (Wildavsky, 1973), difficult to define (Reade, 1983) or no better than non-planning (Banham et al., 1969) is based on a very narrow view of planning as statutory planning.

2 Imagination: what is planning’s spirit and purpose?

Introduction

The planning imagination has been at work in the way we have built cities, but what kind of imagination has been apparent, across which actors, to what ends, and what might that imagination look like in the future? The urban planning imagination is not the exclusive property of one set of actors. Urban planning’s spirit and purpose (Bruton, 1984) will be found in new and productive mixes of imaginations regarding present and future urban planning challenges.

We should not confuse the future orientation of the urban planning imagination with a loss of historical perspective, for planning needs to ‘broaden its preoccupation with space, and to take consideration of time’ (Wilson, 2009: 232). History plays into the present and future of urban planning in complex, non-linear ways in which the imaginative aspects of planning make it ‘a kind of compact between now and the future’ (Abram and Weszkalays, 2011: 8). Geography is part art, part science (Entrikin, 1991). Likewise, ‘making plans for places is more craft than science’ (Hoch, 2019: 4). Indeed, ‘plans are unique forms of public policy. Both art and science, they embody a vision of the future for which there is no proof’ (Hanson, 2017: 262). We should not confuse the ordering of settlement space with the inexorable contiguous growth of a city, since the decline and abandonment of cities has a long history. Relational senses of place have flourished within which the city can be understood not merely as a bounded place but also as a node within networks of places or a nexus of flows or virtual connections. These sensibilities reveal the uniqueness of places and the commonalities produced through connection.

This geohistorical sensibility describes urban planning’s value to societies, capitalist or otherwise. The imagination of urban planning exceeds that of history or geography in that it has a normative aspect – the desire to produce better (or good) urban places. The urban planning imagination is a force for integration and inclusion in a world in which we can all too easily grow further apart. We would have to invent it if it did not already exist.

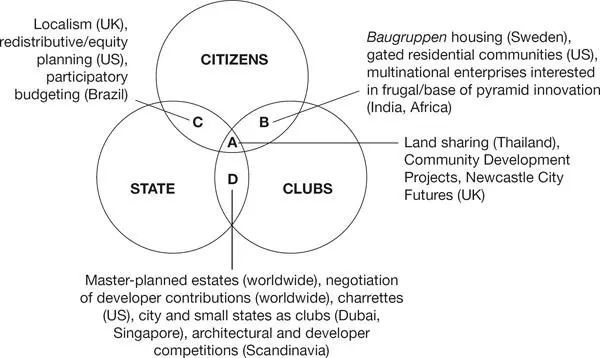

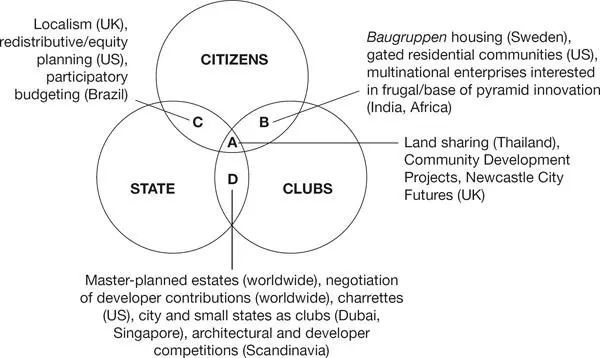

By way of simplifying the story, I refer to three sets of urban planning actors: citizens (as individuals or households), clubs (e.g. multinational enterprises (MNEs), associations of mutual interest, private enterprises) and modern nation states (their local governments and the international interstate system). Recognition of the different actors central to urban planning throughout history implies nothing essential of the motives, the substantive interests or expertise, the wisdom, the geohistorical sensibilities, the sophistication of the methods involved, or the outcomes achieved. The motivations that lie behind acts of urban planning can be obscure both at the time and afterwards and are rightly open to scrutiny, debate, argument, objection and protest. It should also be clear that the urban planning of clubs and states is hardly any less varied in its motives and outcomes than that of myriad citizens. There is as much variety within each category of urban planning actor as there is between citizens, clubs and states. There is yet more variety to uncover in the ‘experimental’ overlaps in the imagination, substantive interests, wisdom and methods of actors – as depicted in figure 2.1. Much of this experimental variety has yet to be recognized, let alone unlocked, as I discuss further in chapter 8.

Figure 2.1 Urban planning actors and mixes of actors

Our settlements are the collective creations of citizens, clubs and states. They are triumphs (Glaeser, 2011) but they are not free from the significant conflicts and imperfections I discuss in chapter 4. Cities are made in our own image and are the physical expressions of both our better and our darker nature. The damage done to the indigenous peoples of Australia and the Torres Straits Islands is testimony to the brutal power of urban planning to deny ancient ways of being-in-place in the process of colonial settlement (Jackson et al., 2017). Elsewhere, in China, planning has been more positively connected to the preservation of ancient urban civilization (Morris, 1994).

One set of these actors can predominate in the planning of cities. The earliest cities of Mesopotamia might be considered concentrations of many citizens. In Europe the city emerged as a club – a municipal corporation – to shield citizens from the powers monopolized by new nation states (Frug, 2000). Cities continue to emerge within the nation-state system in many privately developed new town clubs across the global north and south. Finally, cities have manifested as states. Minus some of the civic ideals, the ancient city states of Athens and Rome have their modern-day counterpart in Singapore.

The balance of these actors in the making of individual cities has varied over time. The historical evidence of a mix of actors notwithstanding, I suggest that new combinations of actors may become the defining feature of urban planning as it is emerging, and we will need to better understand the possibilities for these combinations rather than be led by prejudice regarding the motives or capacities of citizens, clubs or states.

Some form of spatial awareness, organization and planning has been vital to survival, since to dwell in a place is to have regard for ‘things to hand’ (Heidegger, 2010). This is the existentialist sense in which planning precedes rationality rather than being guided by it (Hoch, 2019). These individualistic urban planning tendencies are an irrepressible aspect of human nature. The mass expression of need for shelter across the global south may instead be latent in the highly regulated planning systems of the global north. Regardless, ‘citizens correctly assume that they know something about planning without having studied it formally’ (Levy, 2016: 94).

On the one hand, then, the continuing concern in the global north to define and protect the planning profession as primarily a statutory activity seems out of place when marginalized peoples – in the global north and south – take into their own hands the task of organizing their housing and, by extension, their immediate neighbourhoods and cities (Miraftab, 2009). The lay knowledge and emotional intelligence of citizens are things we might reasonably wish to better incorporate into the planning of our cities (Hayden, 1997; Hoch, 2019). Yet it is as well to remember that ‘Citizens, like elites, can be misguided and self-serving’ (Fainstein, 2010: 32), whether in NIMBY (‘not in my back yard’) protests against development or in opportunistic capturing of the spoils of urban development. In the absence of political will and bureaucratic resources to address vexed issues of compensation and betterment ( chapter 4), local government planners can appear powerless to shape equitable outcomes from the development of cities.

Читать дальше

![Nicholas Timmins - The Five Giants [New Edition] - A Biography of the Welfare State](/books/701739/nicholas-timmins-the-five-giants-new-edition-a-thumb.webp)