1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...27

|

Basis of Criticism |

Character |

Role of Theory |

| External criticism |

Contradiction between external standard and existing practices |

Constructive |

Normative theory as ‘judge’ |

| Internal criticism |

Contradiction in the sense of inconsistency between internal ideals and reality |

Reconstructive |

None |

| Immanent criticism |

‘Dialectical’ contradiction within the constellation, crisis |

Transformative |

Necessity of analysis to demonstrate contradiction in crisis |

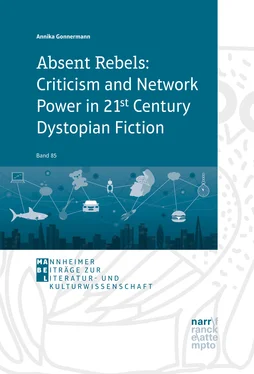

Fig. 1: Rahel Jaeggi – Models of Criticism (excerpt, cf. 213);

With her taxonomy of criticism, Jaeggi has provided the necessary tool for analysing the difference between classical and contemporary dystopian fiction. Applying her terms, the following analysis will show that progressive contemporary dystopian fiction relies on immanent criticism, whereas classical dystopian fiction is connected to external criticism. This, as will be argued, is due to the change in focus and object of critique: from totalitarianism to neoliberal free market philosophy. In order to trace this shift, the following two sub-chapters will focus on what I call classical dystopian fiction, its focus on totalitarianism, and its use of external criticism. I will trace the function of critique within the classical fiction by Orwell, Huxley, and Co. before comparing their approach to the different methods and styles of contemporary dystopias and their immanent criticism strategy targeted at a neoliberal market ideology.12

3.1. Classical Dystopian Fiction, State Totalitarianism, and ‘External Criticism’

Whoever aspires to the articulation of final absolute truth about man and society has already planted the seed of tyranny. (Milovan Djilas quoted in Gottlieb 33)

According to Fredric Jameson “[u]topia has always been a political issue” ( Archaeologies xi). Although he concedes that this nexus constitutes “an unusual destiny for a literary form,” many definitions support exactly this classical connection, building their attempts to demarcate the genre through an analysis of content. Raymond Williams, for instance, concentrates on the nature of the society presented in dystopian works, before categorising the novels accordingly (cf. 95). Others have worked with the same mechanism to uncover a clear focus of the genre: dystopia’s traditional occupation is the topic of state power, and the abusive structures of authoritarian and totalitarian governments (cf. Suvin’s definition). Dystopia has been defined as “a fictional portrayal of a society in which evil, or negative social and political developments, have the upper hand,” dealing with “the quasi-omnipotence of a monolithic, totalitarian state demanding and normally exacting complete obedience from its citizens” (Claeys, “Origins” 107).1 The genre “articulates a specifically political agency ” (Moylan quoted in Donawerth 30) and “describe[s] a variety of aspects and with some consistency an imaginary state or society” (J. Max Patrick quoted in Sargent 7). Accordingly, it has been described as a “ draft of a state , based on a certain ideology […] [typically] an authoritarian, omnipotent state structure , which will triumph over individualism” (Layh 155, own translation), warning “of state structures , which reduce the individual to a marionette without will and consciousness” (Zeißler 9, own translation).2

This focus on the state as object of investigation is grounded in two aspects. Firstly, dystopia’s state preoccupation results from its close generic connection to eutopia, which “is inextricably linked to modernity and to the state-form” (cf. Tally Jr. 3).3 Secondly, according to Tom Moylan, this focus on politics has its roots in the origins of the genre, which “begins to sharpen as the modern state apparatus (in the Stalinist Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, social democratic welfare states, and right-wing oligarchies) is isolated as a primary engine of alienation and suffering” ( Scraps xii). This focus on totalitarian states is evident in the classics of the genre, or the works of the “the big three” (Beauchamp 58), Huxley, Orwell, and Zamyatin, which “relied on a totalistic state to control time and space, history and memory, experiences and possibilities” (Stillman 377). Some 50 years after their publication they continue to define the genre’s standards and self-understanding (cf. Zeißler 9).

Classical dystopian fiction traditionally works within the parameters of external criticism. Its focus on totalitarianism and state policies predestines an external criticism approach that supports an alternative way of living. As a first step, these novels usually flesh out the totalitarian world in all its gruesome details, smattered with scenes of surveillance, hardship, violence, famine, war, indoctrination, public hangings or torture. Implying that these worlds are merely the logical conclusion of the current state of affairs, these novels warn that totalitarianism is just around the corner unless we change things now – a horrific image for readers whose cultural memory stores two world wars and the times thereafter. As Friedrich and Brzezinski argue, totalitarianism is defined by characteristics that deter and repel: a single, simplistic ideology encompassing all aspects of existence; a single mass party typically led by one individual turned dictator, supported by a fanatic hard-core following; a system of police control and surveillance, terrorising the public; and a centrally directed economy (cf. 9f). In The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), Hannah Arendt elaborates on this analysis by stressing the consequences for the individual: “[t]otalitarian domination […] aims at abolishing freedom, even at eliminating human spontaneity in general” (405; cf. also Voigts, “Totalitarian” 54). In order to condemn totalitarian societies, the great majority of dystopian novels advertises libertarian socialist ideas,4 that is to say, ideals informed by a militant anti-totalitarianism, in the form of humanistic maxims such as individuality, creativity, and freedom as expressed by both negative and positive freedom rights (cf. Jacoby, Imperfect xiii).5 As Terry Eagleton argues, alternative universes “have been largely the product of the left” (“Utopias”) and Ken Macleod even states that “the political philosophy of sf [and dystopia] is essentially liberal” (231). Darko Suvin, one of the most renowned science fiction scholars of all time, calls these works of fiction “Jeffersonian” (“Bust”), meaning that they demand the right to life, liberty, and happiness. Indeed, Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Huxley’s Brave New World , and Zamyatin’s We clearly champion a libertarian perspective in the face of totalitarianism and state control and demand the introduction of a more liberal ideology based on humanist notions. External criticism here equals the substitution of totalitarianism (object of critique) by democracy (externally imposed standard).

Dystopia’s means of libertarian criticism are of a narrative nature; showcasing the most despicable features of totalitarianism, these novels and their critique are often wrapped up in a didactic set-up that leaves little if any room for ambiguity. Classical dystopian texts resort to a handful of genre characteristics that have proven to work well in a didactic context: the character structure of both main character and antagonist, the distribution of sympathy, a plot structure based on hegemony and resistance, and the location of hope (usually) outside of the text.

Читать дальше