Dissociation from conventional philosophy

Conventional philosophy starts from ordinary language concepts such as “justice” or the “meaning of being”. Kant even says derisively that it “gropes about concepts”. It does not care about reality, but about what philosophers have said. As the experiment is to science, so is the quote to philosophy. Philosophy seeks wisdom—a wisdom, however, that is not based on knowledge, but is a shot in the dark.

The hypotheses of philosophy cannot be proved scientifically—there are only philosophers, whose thoughts can be studied. They have published at least a million printed pages over the centuries, in which the majority—in line with the nature of such philosophising—are concerned with refuting others; some even turn their backs on their own published works. Thus even studying them all does not lead to universally applicable knowledge.

Structure of the concept

The Concept of Uncompromising Humanism makes no assumptions about anything in advance, nor does it presuppose any specific knowledge. It proceeds on the basis of perception and comes to conclusions using intuitive logic which readers can reconstruct for themselves, including concepts such as the theory of relativity or the hypercycle (the origin of life).

Ludwig Wittgenstein,

1889–1951

Friedrich Hegel,

1770–1831

Before Kant, and to Kant himself, it was taken for granted that philosophy was able to acquire all available knowledge. However, at the start of the 19th century science began to move at a speed that philosophers could no longer follow—and even if they did, they were soon left behind by the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. They fell back on “the clarification of propositions”,Wittgenstein and some even resorted to mysticism, which is not what they should aspire to—rather, they should acquire the fundamental knowledge, move beyond it and perform their former tasks on the basis of this new, magnificent structure.

Consciousness radically expands the horizons of the conscious being—spatially, temporally and socially—especially as it includes the conscious being as the “self”. As expanded horizons offer both possibilities and threats, the consciousness has to interpret everything it perceives within them. If it lacks knowledge, it manages with assumptions and assertions; but as world history makes clear, it is knowledge that brings the greatest success. The selection criterion in the obtaining of knowledge is freedom from contradiction, firstly with regard to reality and secondly with regard to all verified knowledge. Ensuring the maximum possible freedom from contradiction serves two purposes, the force of a statement and its completeness.

The inevitable conclusion is that a model explains the whole or it explains nothing. It is only complete if it explains not only the world, but also the thinking behind the explanations. Despite all attempts at didactic concentration, the quantity of knowledge to be processed for conclusiveness is extensive. This is not all—anyone who embarks on it will only know once they have made the investment whether it was worth it.

A closed circuit of statements? Sciences explain circumscribed reality in terms of circumscribed reality, and thus have by now built up an exponentially increasing, enormous body of knowledge; and yet no-one feels responsible for the consistency of the whole. Philosophers after Hegel have capitulated before the task, even sneering at those small-minded people who attempt it despite their warnings.

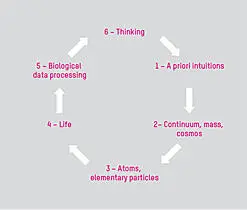

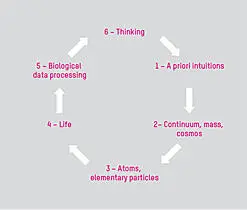

The basis for the Concept of Uncompromising Humanism is formed by the way in which the consciousness imagines the world to be; it ascends in stages towards the thinking that produced this imagining:

1. A priori intuitions. Kant Space and time ineluctably form the coordinate system in the human brain, within which it represents the world.

2. Continuum, mass, cosmos. A continuum logically and essentially fills the perceived space—from Anaximander to Einstein. In “deductive physics”*, on which the model is based, mass is derived as the dynamic of an appropriately-specified continuum, and this continuum carries the expansion of the universe.

3. Atoms, elementary particles. The interaction of dynamics of masses produces interference phenomena that are the basis of all that is perceived. Elementary dynamics are structured into atoms, and atoms into inorganic molecules and, under appropriate circumstances, into organic ones.

4. Life. The huge accumulation of organic molecules on Earth led in a single event to a hypercycle of mutually-determining molecules: the basis for life. As far as is known to date, this has occurred only on Earth.

5. Biological data processing. In the course of evolution, the interaction between cells and cell structures was increasingly augmented by meetings between simple representatives of biochemical states—by means of signals in conductive pathways, ganglia, brains.

6. Thinking. Biological data processing gave rise to thought, which cannot avoid perceiving the world as a body in the coordinates of a priori intuitions.

The ontological circle answers the question “what can I know?”, with which Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” is concerned. However, beings with the benefit of consciousness do not have ontology as their primary aim, but happiness in their own lives. They demand answers to the kind of questions posed by Kant in his “Critique of Practical Reason”: “How should I act? What can I hope for?”, and to the question of how societies should be organised politically, economically, culturally. The basis for answering these questions is the certainty of the existence of free will. Kant postulated this without further ado, while current research into the brain questions it. The Concept of Uncompromising Humanism recognises it by its indispensable function, that of evaluating and selecting the solutions that thinking produces for the world, where instinct alone is not sufficient. In the space opened up by free will the possibility of successful life emerges—“happiness”.

Ontological circle

The Concept shows what successful individual life is and what leads to it, and also what are the conditions for it: the “enabling state” and its prerequisite, “enabled citizens”. Each presupposes the other, both are derived from the preceding stages and form the foundations for the postulation that “all people could be equally happy”.Lichtenberg

Georg Christoph

Lichtenberg, 1742–1799

Each piece of scientific knowledge is based on a proposal that has “stood the test on the touchstone of real-ity”.Kant In the Concept of Uncompromising Humanism, this proposal is the whole. It passes the test, as each of its stages are proven science and each stage emerges strictly from the previous one. It thus becomes clear that knowledge is that which is built up by consciousness and not, as Plato would have it, items in an inventory of knowledge that predated humans, to which they gain access gradually.

Читать дальше