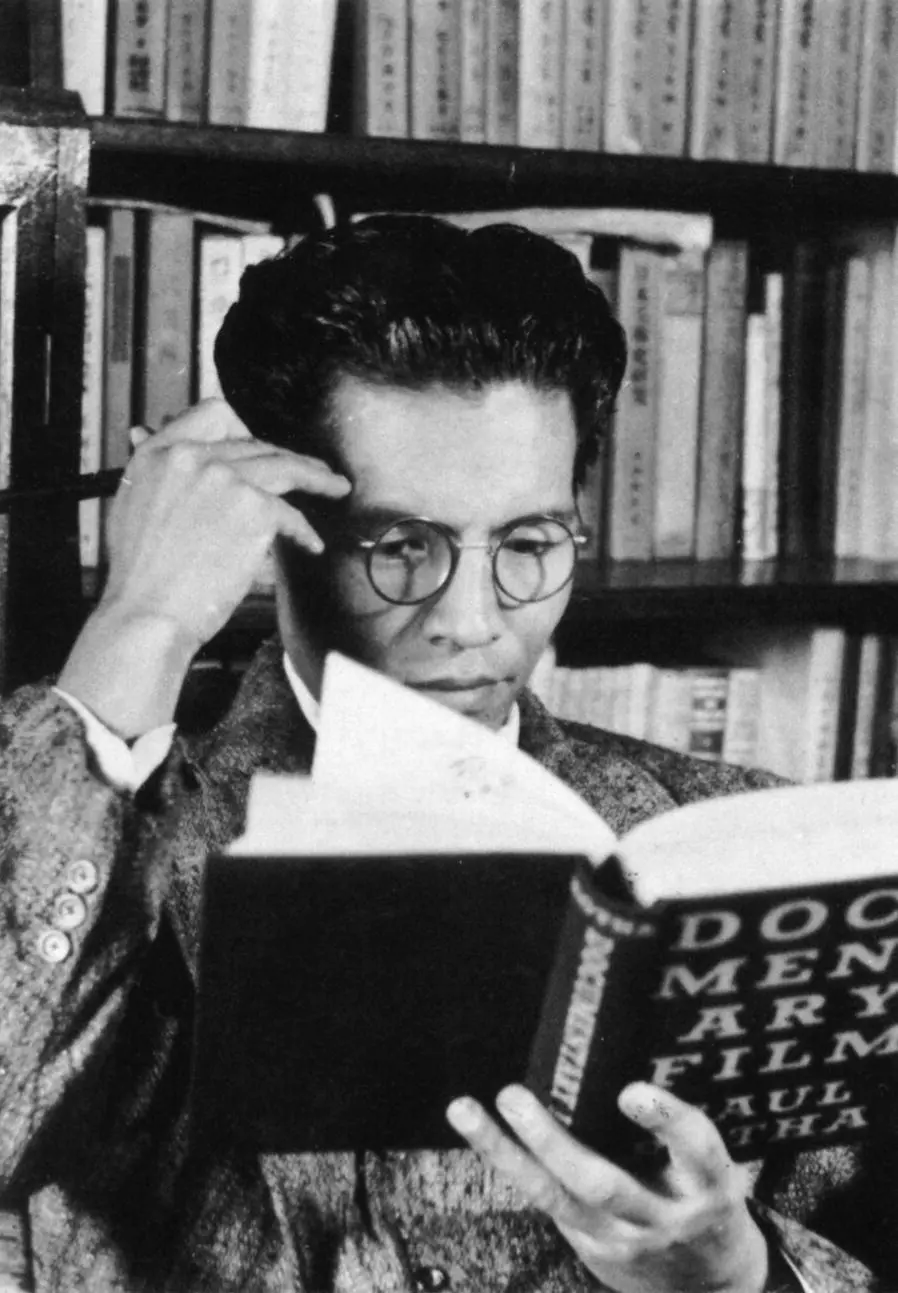

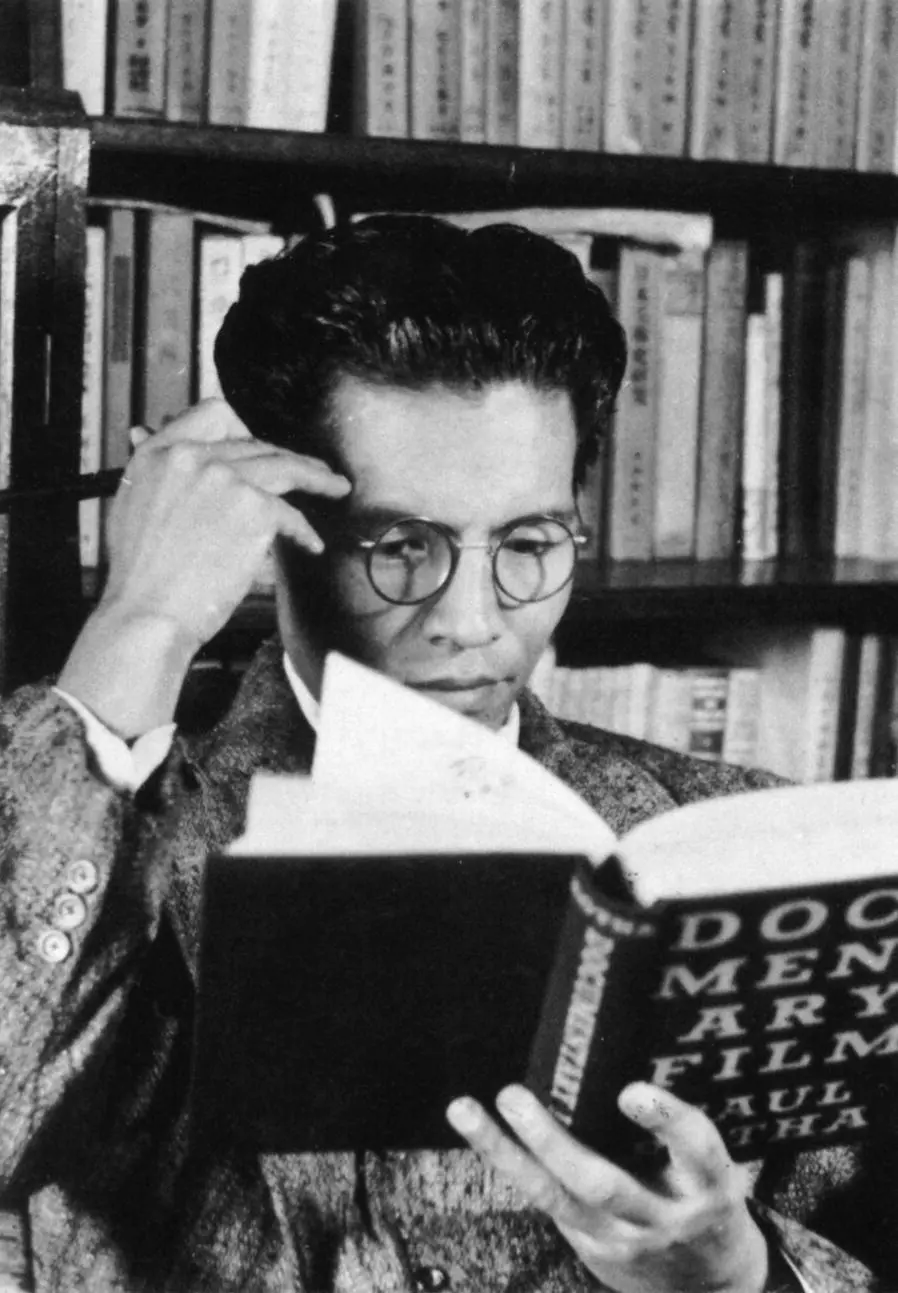

Figure 3.1 Imamura Taihei.

Imamura begins his chapter by pointing out his fellow Japanese critics' conventional misunderstandings of Rotha's documentary theory. While these local interpretations frame Rotha as a kind of “formalist” who rejected fiction film tout court , Imamura rightly reminds the reader that what Rotha criticized was not fiction film as a whole but the capitalist basis of the film industry that had privileged this genre as the most important form of film practice. Similarly, Imamura speaks highly of Rotha's promotion of documentary as the most effective tool for mass propaganda, writing that Rotha's documentary theory “reflects [his] strong social consciousness … and is based on the contemporary mass public's most urgent/real demand,” and that it thus should be respected above all for its unflinching aim to “enlighten the people politically, to turn their eyes to fundamental contradictions in the modern social system” (Imamura 1952: 153–154). Highly sympathetic to Rotha's promotion of documentary's mission of social reform, Imamura goes even so far as to declare that “under Rotha's opinions lies the idea of socialism, and in this sense his ‘documentarism’ shares commonalities with that of the Soviet Union” (Imamura 1952: 154). As a Marxist writing before Nikita Khruschev's critique of Stalin's cult of personality, Imamura uses a comparison with the legacies of Soviet Union's revolutionary model of film practice in the 1920s – which had huge impact on the Japanese left in prewar Japan despite severe state censorship – as the highest compliment for Rotha's political consciousness. 7

Despite these general accolades, Imamura is highly critical about Rotha's own theorization of documentary. For instance, he condemns Rotha's inclusion of Potemkin and other examples from the Soviet Union within the category of documentary, arguing that these films should be treated as what he calls “semi‐documentary.” Although they use some basic methods borrowed from documentary, films that present us with a reenactment or reproduction of historical events, he argues, must remain in the realm of fiction because “they did not record the facts [ jijitsu ] themselves” that took place in front of the camera (Imamura 1952: 160–161). Moreover, after concisely paraphrasing Rotha's idea of dramatization – “rather than showing the fact as it is, one should change it at one's discretion by filtering it through our subjectivity so that certain principles behind it are revealed” – he abruptly dismisses it by saying “this statement is so illogical that it is hard to grasp its meaning” (Imamura 1952: 166). Likewise, Imamura's unsympathetic judgment is applied to Rotha's application of dialectics. “It seems apparent,” he writes, “that this [Rotha's reference to dialectics] is nothing more than a mere repetition of Eisenstein's dialectic of collision, and in this instance, too, the term ‘dialectic’ serves as a magic spell. In depicting anything, this position deems it to be enough to see the collision of things, and, as a result of this collision, lead to the dialectical formula composed of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. This is the most foolish part of Rotha's Documentary Theory ” (Imamura 1952: 176). 8 Imamura concludes his reading with a highly self‐contradictory remark: “As I have shown, Rotha's Documentary Theory contains a lot of inaccurate terms used in an idiosyncratic manner, but if we try to understand what he meant to say as a whole, then we come to realize that it has very correct views” (Imamura 1952: 167).

Imamura's schizophrenic interpretation of Rotha's text was inseparable from his own determination to fight against domestic opponents of documentary film practice. In other words, he deployed Rotha as a mouthpiece through which his own theory of documentary could be disseminated. What are, then, main characteristics of his theory, and how do they differ from Rotha's? First, in contrast to Tsumura's discussion of the philosophical difference between actuality and reality, Imamura introduces a third term “fact” ( jijitsu ) as the foundation for what he considered to be kiroku eiga (Imamura uses this category in the same way as Tsumura, meaning nonfictional films in general). To be sure, Imamura does not ignore the creative intervention of the human agent in the capturing of the fact, as he likens the operation of montage to that of the human cognition in his earlier publications such as Theory of Documentary Film (Imamura 1940: 26). But his film theory in general repeatedly emphasizes that the factuality of filmic representation is guaranteed by the mechanical nature of the photographic image, which is able to capture what has been invisible or unknowable to the human perception, to grasp an object's motion as it simultaneously moves before the camera, and to reproduce identical images at all times. In Imamura's view, it is this mechanical nature of the photographic image that distinguishes cinema from the traditional arts, and, just like the late Kracauer, he argues that “one can understand film's property by knowing the features of the photography that constitutes this medium's basic units, structural elements, and historical origin” (Imamura 1957: 97–99). And as long as it makes use of those mechanical/photographic features properly, kiroku eiga – or what he now calls the “cinema of facts” ( jijitsu no eiga ) – must be placed higher than geki eiga – or the “cinema of fiction” ( kakū no eiga ) – in the historical development of film practice (Imamura 1957: 137). As expected, Rotha's documentary theory is evaluated only in this light; although Rotha clearly differentiated his conception of documentary from the descriptive and objective treatment of the facts found in newsreels or educational films, Imamura tactically interprets him as someone who “paid attention to the film's recording ability and came to believe that the real beauty lies only in the documentation of the fact” (Imamura 1952: 154).

Another, and perhaps most telling, characteristic of Imamura's documentary theory is his tireless effort to make generic distinctions between fiction and nonfiction films, and, ultimately, to defend the latter as a superior form of film practice. Like Tsumura's argument on the philosophical distinction between reality/fiction and actuality/documentary, Imamura's formula appears to be somewhat schematic, but with a different emphasis. In fiction film, Imamura argues, all aesthetic efforts are made “to exhibit the necessity [ hitsuzen ] as the contingent [ gūzen ],” whereas documentary film aspires “to reveal the necessity among the contingent” (Imamura 1955: 107). Imamura tries to prove the legitimacy of his formula by connecting it to recent trends in postwar film culture. After its long, indulgent tenure in the dream‐like world of fiction, he says, cinema is now consciously beginning to recuperate its social function through different uses of the medium, as represented by the recent upsurge of the so‐called “semi‐documentary” films such as Roberto Rossellini's Paisan ( Paisà , 1946), René Clément's The Damned ( Les maudits, 1947), and Jules Dassin's The Naked City (1948). One the one hand, this ongoing move toward a more concrete and down‐to‐earth filmic representation/documentation of the actual world outside the studio is a necessary result of the catastrophic destruction of reality as such brought about by the world war, for contemporary audiences “are eager to see in the movies not melodramas but vivid reflections of their own life due to radical changes in their living conditions” (Imamura 1955: 113). One the other hand, the continuous development and increasing availability of recording devices (e.g. small‐gauge cameras and cheaper film stocks) through mass production promises progress toward the perfect realization of what Béla Balázs once called the period of “visual culture.” In this period, he argues, individuals would no longer remain in the position of mere passive receivers segregated by language barriers but would begin to directly communicate with each other by becoming witnesses, reporters, and even protagonists of ongoing historical events. According to Imamura, a new and promising form of film art should arise from this “vernacularization of cinema” ( eiga no nichijōka ) as a personal mobile tool for the documentation of the everyday (Imamura 1955: 114).

Читать дальше