The disease involves dissemination of virus throughout the host and infection of the skin. Indeed, the pathogenesis of mouse pox described in Chapter 3provides a fairly accurate model of smallpox pathogenesis. The virus encodes growth factorsthat were originally derived from cellular genes. These growth factors induce localized proliferation at sites of infection in the skin, which results in development of the characteristic pox (see Chapter 18, Part IV).

Infection of an “accidental” target tissue leading to permanent damage despite efficient clearing

As outlined in Figure 4.2, some viruses can target and damage an organ or organ system in such a way that recovery from infection does not lead to the infected individual regaining full health despite generation of good immunity. A well‐understood example is paralytic poliomyelitis. Poliovirus is a small enteric virus with an RNA genome (a picornavirus), and most infections (caused by ingestion of fecal contamination from an infected individual) are localized to the small intestine. Infections are often asymptomatic, but can lead to mild enteritis and diarrhea. The virus is introduced into the immune system by interaction with lymphatic tissue in the gut, and an effective immune response is mounted, leading to protection against reinfection.

Infection with poliovirus, however, can also lead to paralytic polio. The cellular surface protein to which the virus must bind for cellular entry (CD155) is found only on cells of the small intestine and on motor neurons. In rare instances, infection with a specific genotype that displays marked tropism for (a propensity to infect) neurons (i.e., a neurovirulent strain) leads to a situation where virus infects motor neurons and destroys them. In such a situation, destruction of the neurons leads to paralysis.

It should be noted that paralysis resulting from neuronal infection does not aid the virus's spread among individuals; this paralytic outcome is a “dead end.” Perhaps ironically, the paralytic complications of poliovirus infections have had negative selective advantages, since if such a dramatic outcome did not occur, there would have been no interest in developing a vaccine against poliovirus infection!

A variation on the theme of accidental destruction of neuronal targets by an otherwise relatively benign course of acute virus infection can be seen in rubella. This disease (also called German measles), which is caused by an RNA virus, is a mild (often asymptomatic) infection resulting in a slight rash. Although infection is mild in an immunocompetent individual, the virus has a strong tropism for replicating and differentiating neural tissue. Therefore, women in the first trimester of pregnancy who are infected with rubella have a very high probability of having an infant with severe neurological damage from congenital rubella syndrome. Rubella is rare in the United States due to high acceptance of the vaccine, but vaccination of women who are planning to become pregnant is an effective method of preventing such damage during localized rubella epidemics in other parts of the world.

Persistent viral infections

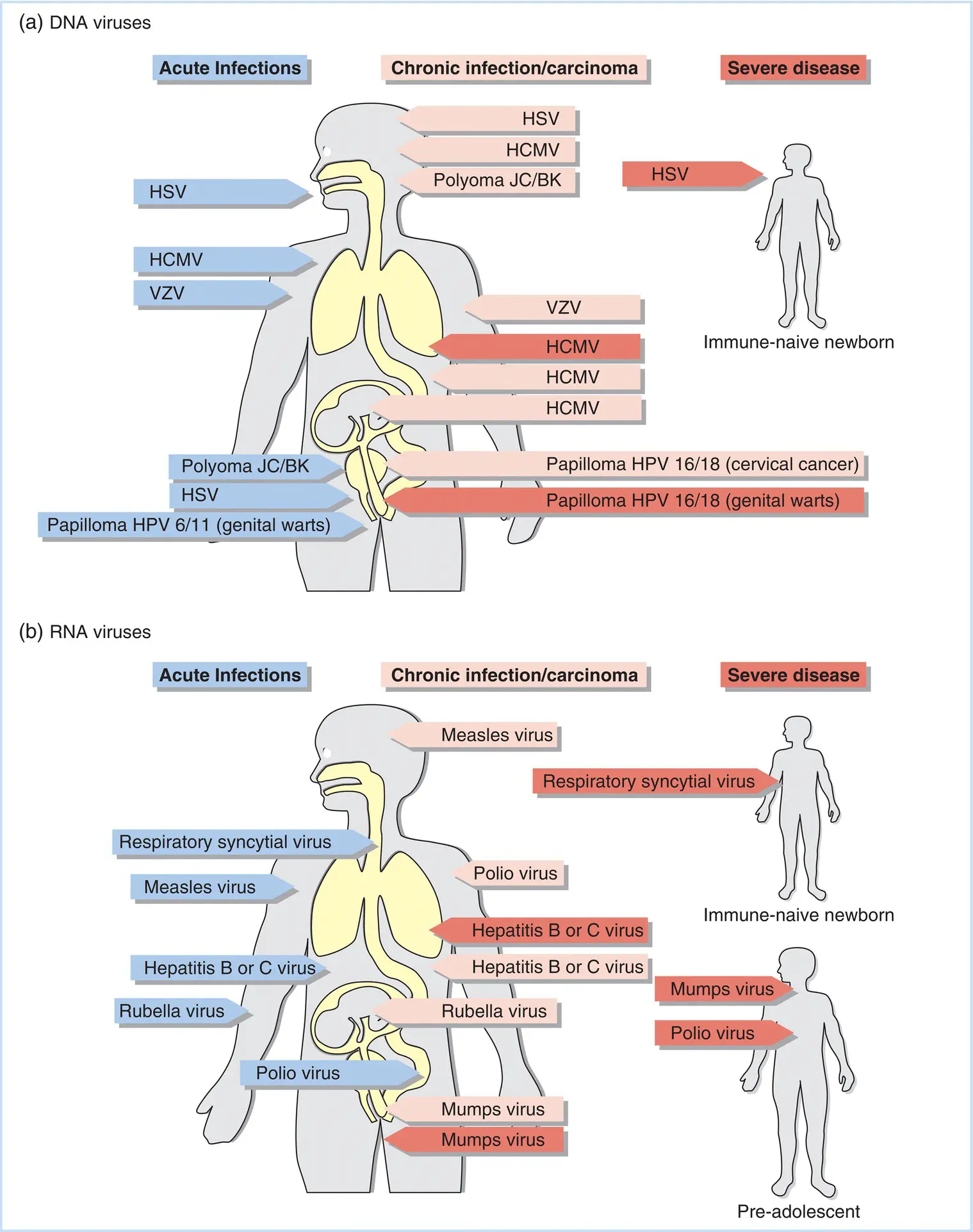

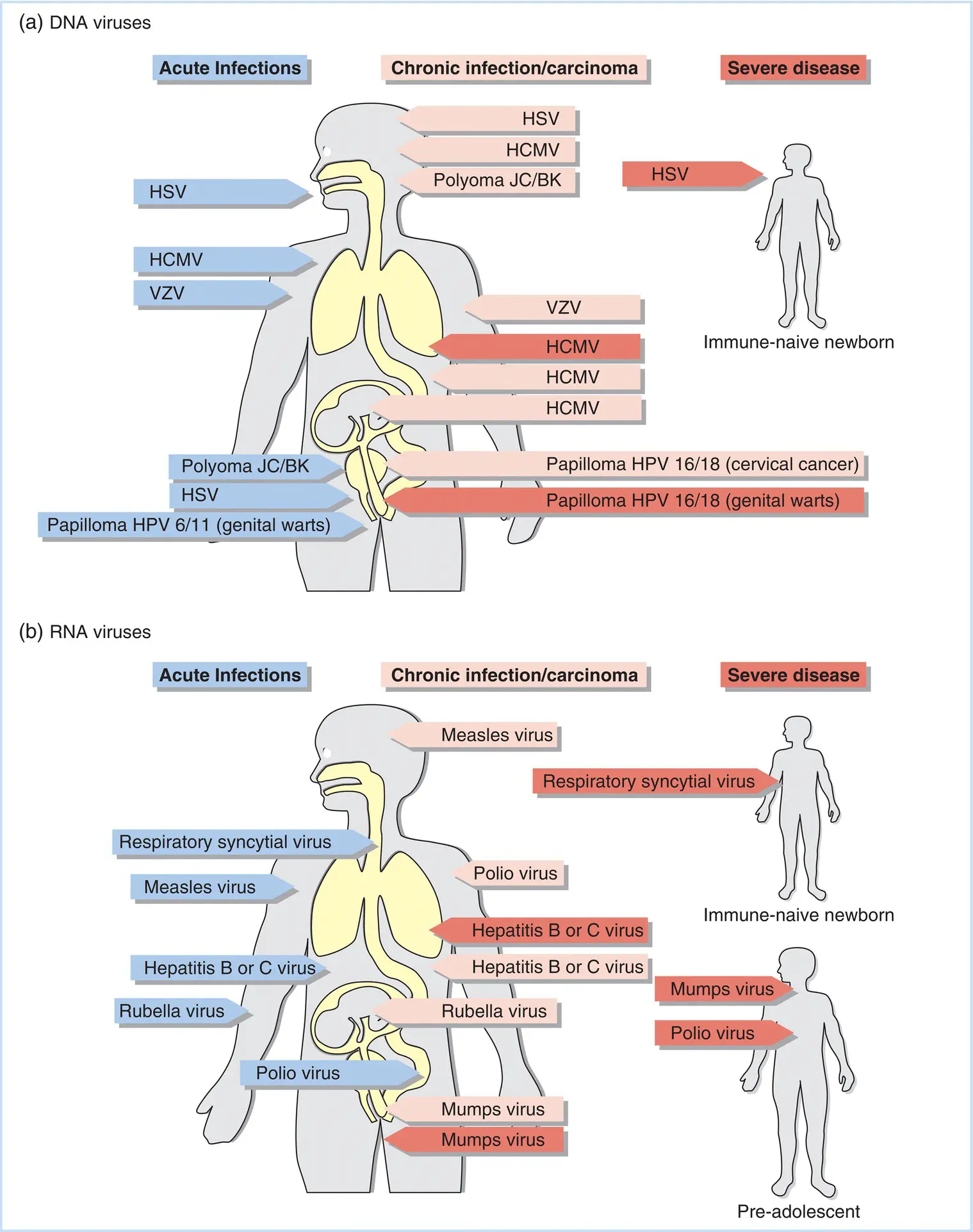

While persistent viral infections often indicate a long history of coevolution between virus and host, the lack of serious consequences to the vast majority of those infected does not mean that debilitating or lethal consequences are not possible. This is especially the case in situations where the immune system of the infected individual is compromised or has not yet developed. Some examples of persistent infections and the complications that can arise from these infections are shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Examples of virus infection of specific organs or organ systems. (a) DNA genome viruses. (b) RNA genome viruses. Blue labels indicate acute infections, while pink labels indicate infections that result in either chronic disease states or carcinomas. Red labels indicate acute infections that can result in severe disease.

Papilloma and polyomavirus infections

Some persistent infections are characterized by chronic, low‐level replication of virus in tissues that are constantly being regenerated so that damaged cells are eliminated as a matter of course. An excellent example described in more detail in Chapter 16, Part IV, is the persistent growth and differentiation of keratinized tissuein a wart caused by a papillomavirus. In such infections, virus replication closely correlates with the cell's differentiation state, and the virus can express genes that delay the normal programmed death ( apoptosis) of such cells in order to lengthen the time available for replication.

The distantly related polyoma viruses, the BK and JC viruses, induce chronic infections of kidney tissue. Such infections are usually asymptomatic and are only characterized by virus shedding in the urine; however, in immunosuppressed individuals, infections of the brain and other organs can be seen. Thus, these persistent viruses have a role in the morbidity of late‐stage AIDS and in persons undergoing immunosuppression for organ transplants.

Herpesvirus infections and latency

As detailed in Chapter 17, Part IV, hallmarks of herpesvirus infections are an initial acute infection followed by apparent recovery where viral genomes are maintained in the absence of infectious virus production in specific tissue. Latency is characterized by episodic reactivation (recrudescence) with ensuing (usually) milder symptoms of the original acute infection. Example viruses include herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), and varicella zoster virus (VZV).

In a latent infection, the viral genome is maintained in a specific cell type and does not actively replicate. HSV maintains latent infections in sensory neurons, whereas EBV maintains itself in B lymphocytes. Latent infections often require the expression of specific virus genes that function to ensure the survival of the viral genome or to mediate the reactivation process.

Reactivation requires active participation of the host. Immunity, which normally shields the body against re‐infection, must temporarily decline. Such a decline can be triggered by the host's reaction to physical or psychological stress. HSV reactivation often correlates with a host stressed by fatigue or anxiety. VZV reactivation leads to shingles, a very painful recrudescence throughout the sensory nerve net serving as the site of the latent virus. Unlike HSV reactivation, VZV reactivation results in destruction of the nerve ganglia and is associated with a generalized decline in immunity associated with aging.

Effective immunity is vital for controlling and maintaining herpesvirus latency and localizing its sites of replication. Newborns not protected by maternal immunity are subject to profound disseminated HSV infections of their central nervous system (CNS; see the “Viral Infections of Nerve Tissue” section) if they encounter the virus, for instance by infection from a mother carrying a primary acute infection. Disseminated human cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections are a major cause of death in individuals undergoing immunosuppressive treatment to facilitate organ transplants. Furthermore, CMV infections of the eye are a leading cause of blindness in patients with advanced immune deficiencies due to infection by HIV. Also, primary CMV infection of a pregnant woman is a leading cause of neurological abnormalities in developing fetuses.

Читать дальше