The establishment of the rival paper, the Citizen, was the signal for a war of words, waxing in bitterness from week to week, and ceasing only with the death of the Arizonian, which took place not long after. One of the editors of the Citizen was Joe Wasson, a very capable journalist, with whom I was afterward associated intimately in the Black Hills and Yellowstone country during the troubles with the Sioux and Cheyennes. He was a well-informed man, who had travelled much and seen life in many phases. He was conscientious in his ideas of duty, and full of the energy and “snap” supposed to be typically American. He approached every duty with the alertness and earnestness of a Scotch terrier. The telegraph was still unknown to Arizona, and for that reason the Citizen contained an unusually large amount of editorial matter upon affairs purely local. Almost the very first columns of the paper demanded the sweeping away of garbage-piles, the lighting of the streets by night, the establishment of schools, and the imposition of a tax upon the gin-mills and gambling-saloons.

Devout Mexicans crossed themselves as they passed this fanatic, whom nothing would seem to satisfy but the subversion of every ancient institution. Even the more progressive among the Americans realized that Joe was going a trifle too far, and felt that it was time to put the brakes upon a visionary theorist whose war-cry was “Reform!” But no remonstrance availed, and editorial succeeded editorial, each more pungent and aggressive than its predecessors. What was that dead burro doing on the main street? Why did not the town authorities remove it?

“Valgame! What is the matter with the man? and why does he make such a fuss over Pablo Martinez’s dead burro, which has been there for more than two months and nobody bothering about it? Why, it was only last week that Ramon Romualdo and I were talking about it, and we both agreed that it ought to be removed some time very soon. Bah! I will light another cigarette. These Americans make me sick—always in a hurry, as if the devil were after them.”

In the face of such antagonism as this the feeble light of the Arizonian flickered out, and that great luminary was, after the lapse of a few years, succeeded by the Star, whose editor and owner arrived in the Territory in the latter part of the year 1873, after the Apaches had been subdued and placed upon reservations.

Table of Contents

TUCSON INCIDENTS—THE “FIESTAS”—THE RUINED MISSION CHURCH OF SAN XAVIER DEL BAC—GOVERNOR SAFFORD—ARIZONA MINES—APACHE RAIDS—CAMP GRANT MASSACRE—THE KILLING OF LIEUTENANT CUSHING.

THE Feast of San Juan brought out some very curious customs. The Mexican gallants, mounted on the fieriest steeds they could procure, would call at the homes of their “dulcineas,” place the ladies on the saddle in front, and ride up and down the streets, while disappointed rivals threw fire-crackers under the horses’ feet. There would be not a little superb equestrianism displayed; the secret of the whole performance seeming to consist in the nearness one could attain to breaking his neck without doing so.

There is another sport of the Mexicans which has almost if not quite died out in the vicinity of Tucson, but is still maintained in full vigor on the Rio Grande: running the chicken—“correr el gallo.” In this fascinating sport, as it looked to be for the horsemen, there is or was an old hen buried to the neck in the sand, and made the target for each rushing rider as he swoops down and endeavors to seize the crouching fowl. If he succeed, he has to ride off at the fastest kind of a run to avoid the pursuit of his comrades, who follow and endeavor to wrest the prize from his hands, and the result, of course, is that the poor hen is pulled to pieces.

Nothing would give me greater pleasure than to describe for the benefit of my readers the scenes presenting themselves during the “Funccion of San Agostin” in Tucson, or that of San Francisco in the Mexican town of Madalena, a hundred and twenty-five miles, more or less, to the south; the music, the dancing, the gambling, the raffles, the drinking of all sorts of beverages strange to the palate of the American of the North; the dishes, hot and cold, of the Mexican cuisine, the trading going on in all kinds of truck brought from remote parts of the country, the religious ceremonial brilliant with lights and sweet with music and redolent with incense.

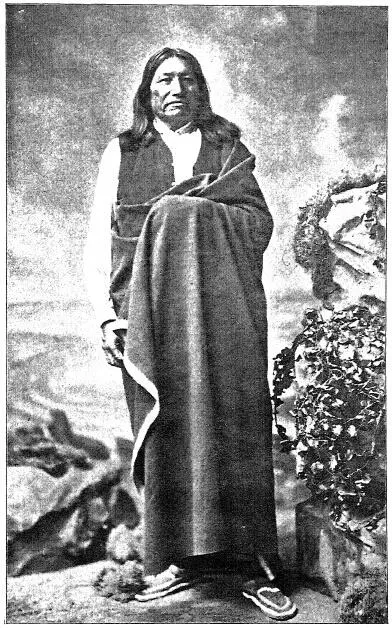

SPOTTED TAIL.

For one solid week these “funcciones lasted,” and during the whole time, from early morn till dewy eye, the thump, thump of the drum, the plinky, plink, plink of the harp, and the fluky-fluke of the flute accented the shuffling feet of the unwearied dancers. These and events like them deserve a volume by themselves. I hope that what has already been written may be taken as a series of views, but not the complete series of those upon which we looked from day to day. No perfect picture of early times in Arizona and New Mexico could be delineated upon my narrow canvas; the sight was distracted by strange scenes, the ears by strange sounds, many of each horrible beyond the wildest dreams. There was the ever-dreadful Apache on the one hand to terrify and torment, and the beautiful ruin of San Xavier on the other to bewilder and amaze.

Of all the mission churches within the present limits of the United States, stretching in the long line from San Antonio, Texas, to the presidio of San Francisco, and embracing such examples as San Gabriel, outside of Los Angeles, and the mission of San Diego, there is not one superior, and there are few equal, to San Xavier del Bac, the church of the Papago Indians, nine miles above Tucson, on the Santa Cruz. It needs to be seen to be appreciated, as no literal description, certainly none of which I am capable, can do justice to its merits and beauty. What I have written here is an epitome of the experience and knowledge acquired during years of service there and of familiarity with its people and the conditions in which they lived.

My readers should bear in mind that during the whole period of our stay in or near Tucson we were on the go constantly, moving from point to point, scouting after an enemy who had no rival on the continent in coolness, daring, and subtlety. To save repetition, I will say that the country covered by our movements comprehended the region between the Rio Azul in New Mexico, on the east, to Camp MacDowell, on the west; and from Camp Apache, on the north, to the Mexican pueblos of Santa Cruz and Madalena, far to the south. Of all this I wish to say the least possible, my intention being to give a clear picture of Arizona as it was before the arrival of General Crook, and not to enter into unnecessary details, in which undue reference must necessarily be had to my own experiences.

But I do wish to say that we were for a number of weeks accompanied by Governor Safford, at the head of a contingent of Mexican volunteers, who did very good service in the mountains on the international boundary, the Huachuca, and others. We made camp one night within rifle-shot of what has since been the flourishing, and is now the decayed, mining town of Tombstone. On still another evening, one of our Mexican guides—old Victor Ruiz, one of the best men that ever lived on the border—said that he was anxious to ascertain whether or not his grandfather’s memory was at fault in the description given of an abandoned silver mine, which Ruiz was certain could not be very far from where we were sitting. Naturally enough, we all volunteered to go with him in his search, and in less than ten minutes we had reached the spot where, under a mass of earth and stone, was hidden the shaft of which our guide had spoken.

Читать дальше