1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...33

| Information and cultural service |

Low (1) |

Medium (2) |

High (3) |

| Ecotourism |

Absence of locations with quality for ecotourism, such as hiking and diving |

Occurrence of at least one location with quality for ecotourism, such as hiking and diving |

Occurrence of more than one location with quality for ecotourism, such as hiking and diving |

| Historical/cultural tourism |

Absence of buildings or areas with known historical value |

Occurrence of at least one building or area with known historical value |

Occurrence of more than one building or area with known historical value |

| Recreation and leisure |

Low recreational quality |

Medium recreational quality |

High recreational quality |

| Scenic quality |

Absence of natural attractions (e.g. cliffs) |

Occurrence of at least one natural attraction (e.g. cliffs) |

Occurrence of more than one natural attraction (e.g. cliffs) |

Primary information collected by methodologies such as the ones applied by Santos and Silva [33], Seppelt et al. [35], and Souza et al. [34] is essential to enable researchers to perform environmental mapping and modeling. Chan and Ruckelshaus [37] reported efforts to map and model ecosystem services, such as the Multiscale Integrated Models of Ecosystem Services (MIMES), Artificial Intelligence for Ecosystem Services (ARIES), and Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST). However, these models are considered recent. Studies about them remain scarce in the literature [31]. The applicability and effectiveness of the adopted tools remain significantly questionable.

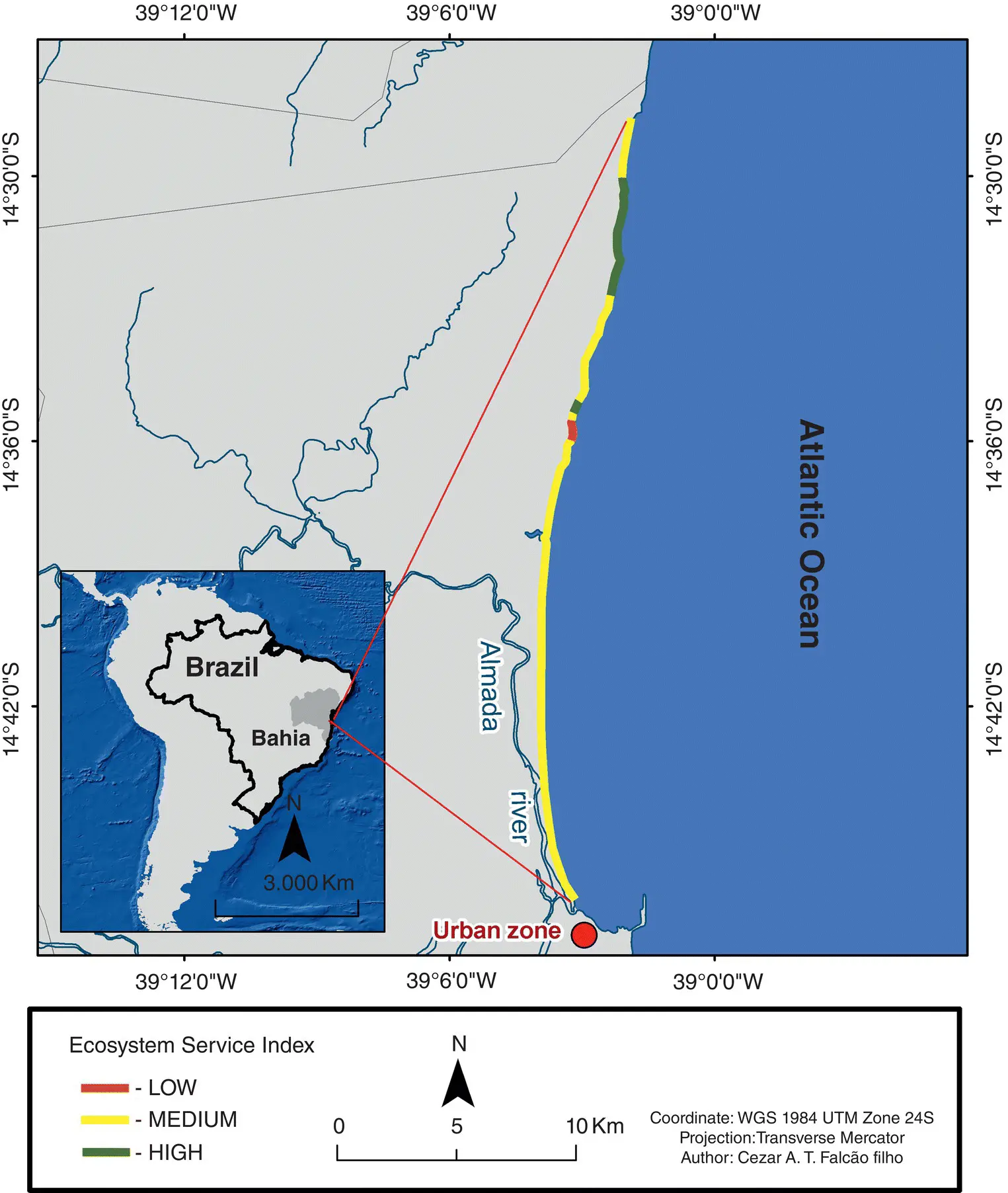

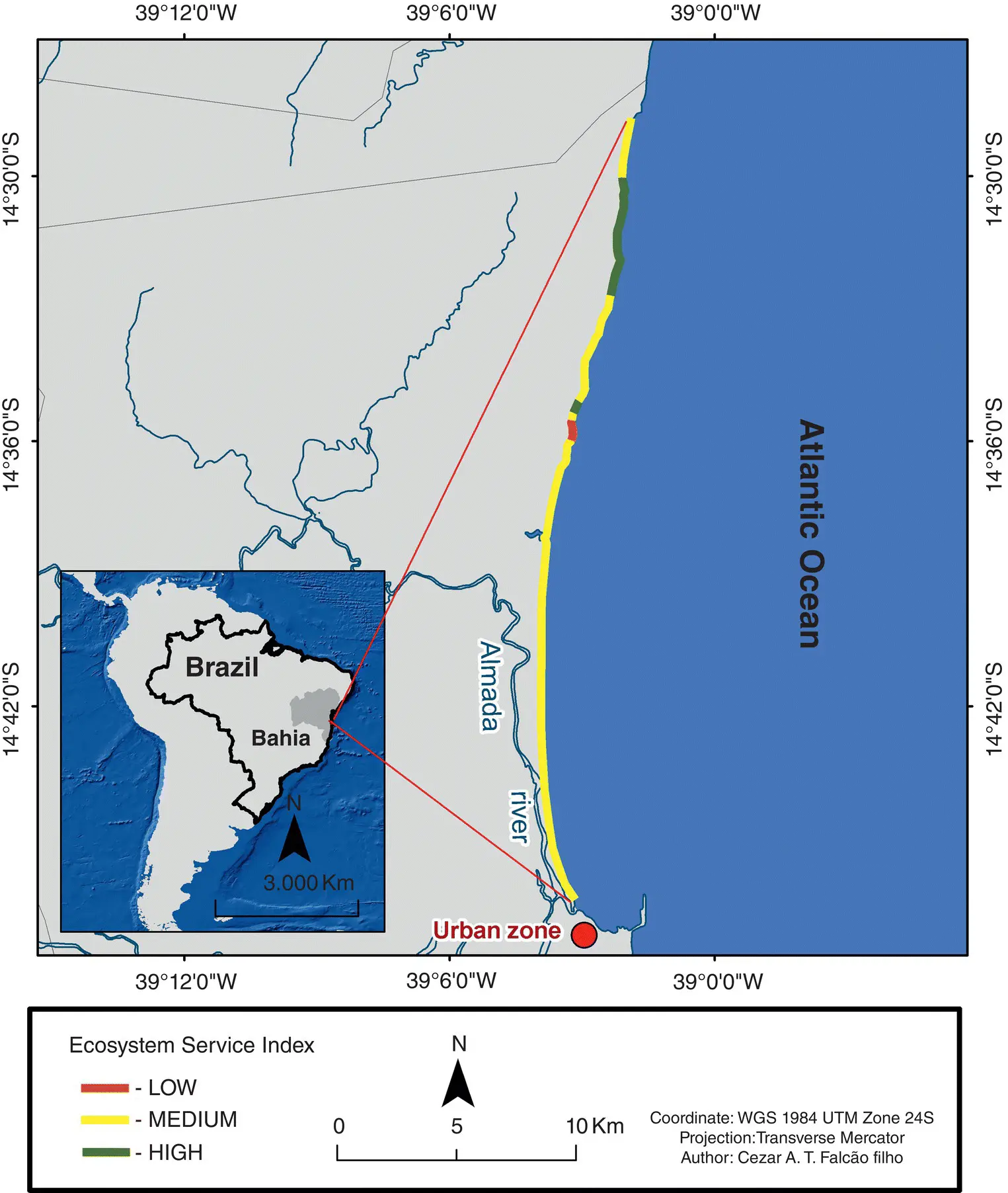

Figure 1.8 Ecosystem service index obtained for the northern shoreline of the municipality of Ilhéus, state of Bahia, Brazil.

It is important to emphasize that the analysis of ecosystem services applied to management and decision‐making processes does not need to include economic assessments [31], as shown in the study by Ruckelshaus et al. [38], who evaluated 20 pilot studies about the application of ecosystem services and concluded that many decision‐makers wished to examine the consequences of their actions for traditional market commodities in monetary terms, as well as the non‐economic benefits, including cultural aspects and biodiversity values. The misconception that the assessment of ecosystem services requires economic assessment can be a barrier to scientific development.

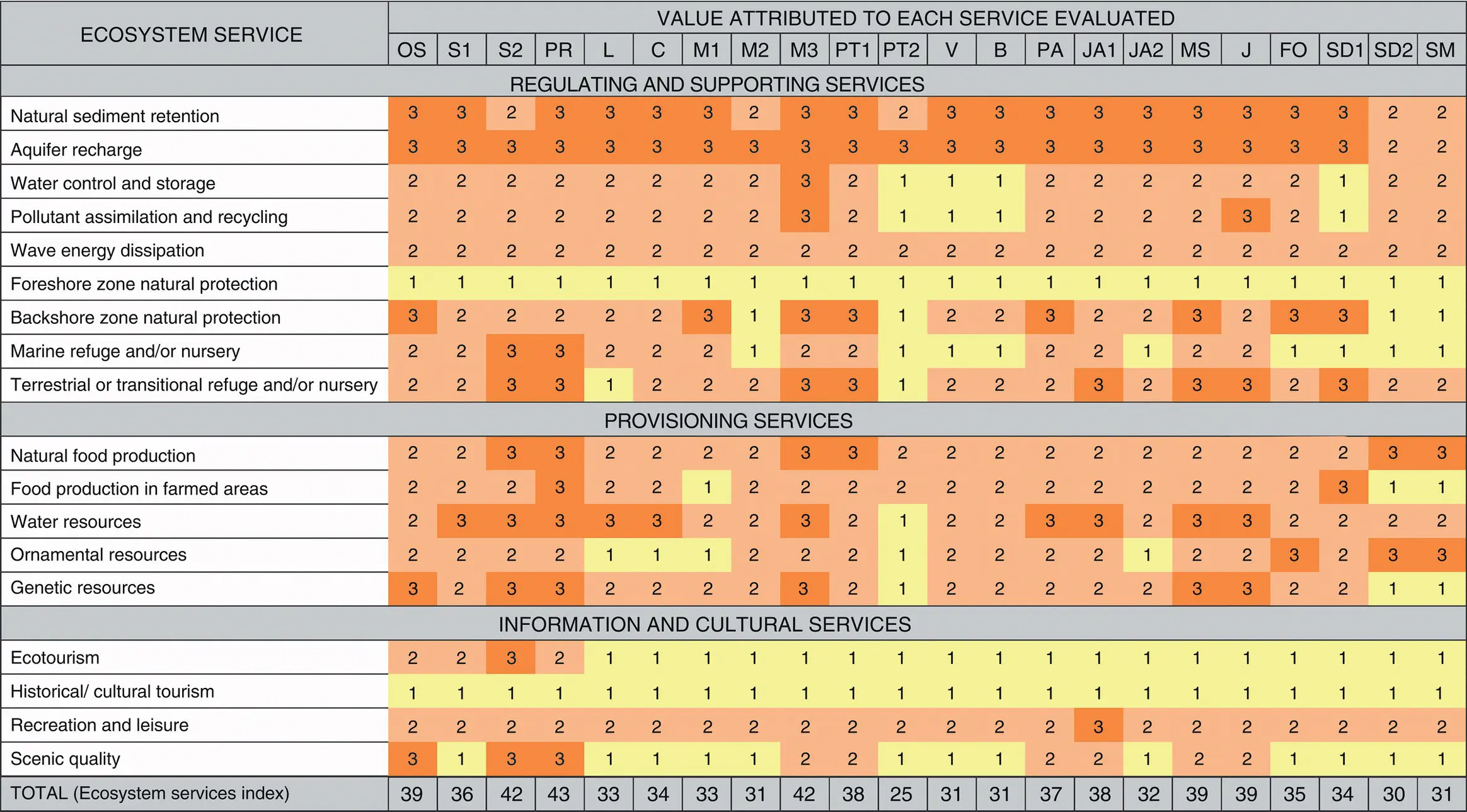

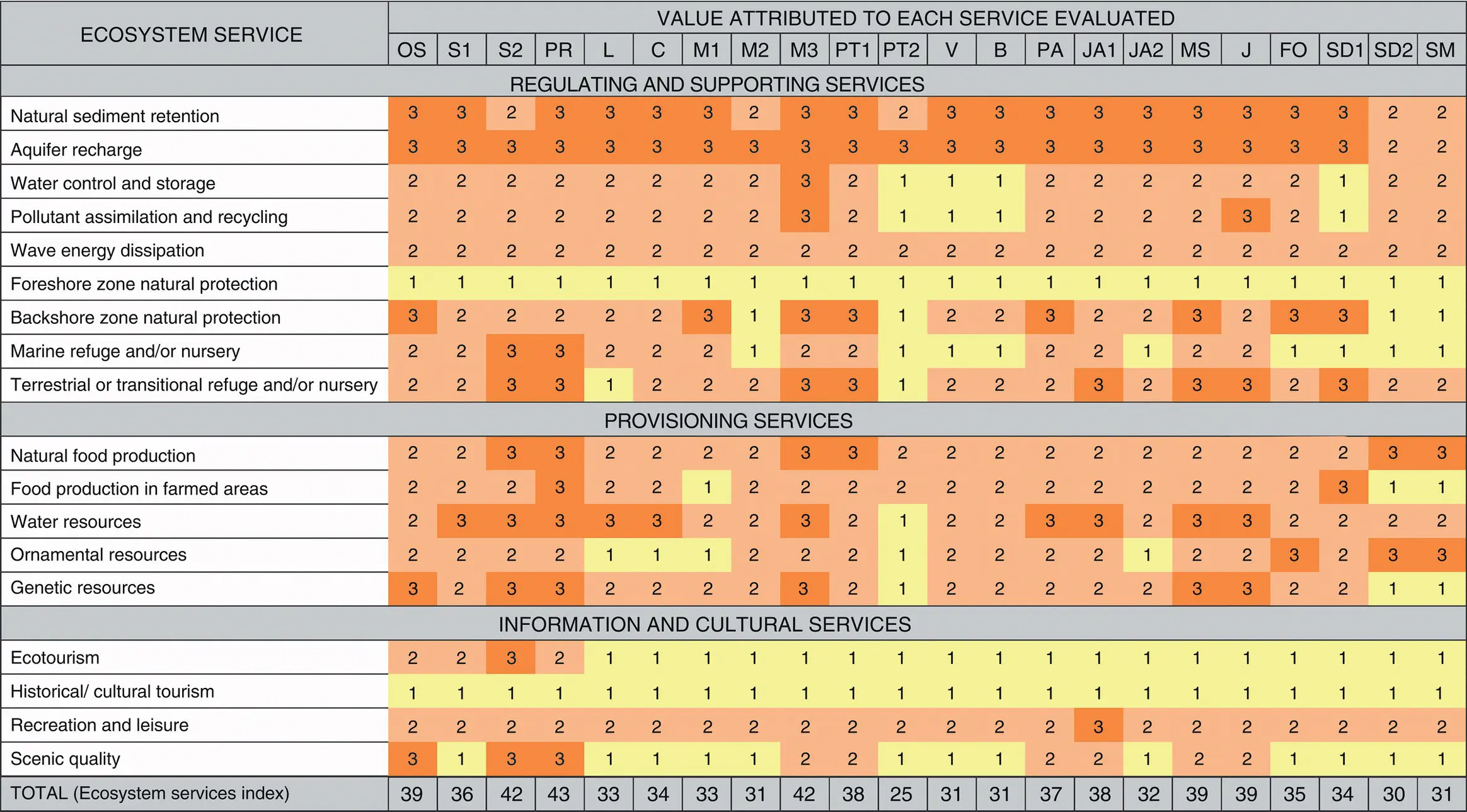

Figure 1.9 Qualitative assessment of ecosystem services by beaches in the municipality of Ilhéus, state of Bahia, Brazil. Northern shoreline beaches – PS: Pé de Serra; S1: Sargi – trecho 1; S2: Sargi – trecho 2; PR: Ponta do Ramo; L: Luzimares; C: Coqueiros; M1: Mamoã – trecho 1; M2: Mamoã – trecho 2; M3: Mamoã – trecho 3; PT1: Ponta da Tulha – trecho 1; PT2: Ponta da Tulha – trecho 2; V: Verdesmares; B: Barramares; PA: Paraíso do Atlântico; JA1: Jóia do Atlântico – trecho 1; JA2: Jóia do Atlântico – trecho 2; MS: Mar e Sol; J: Japará; FO: Fazenda de Osmar; SD1: São Domingos – trecho 1; SD2: São Domingos – trecho 2; SM: São Miguel.

As the concept of ecosystem service increasingly becomes an operational tool, it is necessary to explain the complexity of the relationships among production, ecosystem service appropriation [22], and impacts on different time and space scales. So far, there has been considerable focus on spatial patterns of ecosystem service provision and appropriation; however, the temporal dynamics have been little explored, as highlighted by Rau et al. [22], who proposed a new way of categorizing ecosystem services based on their temporal dynamics by differentiating linear from nonlinear dynamics in the provision and appropriation of these services.

The authors above have suggested that temporal dynamics can be better integrated into studies about ecosystem services through four stages: (i) defining the appropriate time limits of the system; (ii) identifying the primary types of ecosystem dynamics; (iii) evaluating the spatial scale at which the dynamics develop in the system; and (iv) developing measures to assess such dynamics.

Considering the temporal dynamics of ecosystem services by following the stages suggested by Rau et al. [22] is a way to better plan the management of ecosystem services.

1.3.2 Agriculture and Ecosystem Services

Agriculture is the most widely managed ecosystem globally since it covers approximately one‐third of the earth's surface. Therefore, given its importance, this item addresses agricultural systems, ecosystem services provided by these systems, and their issues, possibilities, and challenges.

Agricultural ecosystems provide food, fibers, fuels, and a range of products essential to human life; thus, they are classified as ecosystem provisioning services. However, agricultural ecosystems depend on many other support and regulation services – such as soil fertility, pollinating agents, and water supplies – to provide these services [16, 39].

There are so‐called ecosystem disservices to agriculture if one considers the most widespread definition of ecosystem services, according to which Nature provides services essential to human survival. All natural ecosystem processes that may reduce productivity or increase production costs – such as herbivory and plants' competition for space, nutrients, and water – are classified as disservices to agriculture [40].

The intensity of the impact that ecosystem services or disservices have on agricultural systems depends on the diversity, composition, and functioning of the landscape surrounding them [41]. Management of ecosystem processes began after humans stopped being hunter‐gatherers and became farmers, based on the degree of service or disservice to agricultural production increase. Management, or manipulation, of processes reached unprecedented levels due to the Green Revolution , 5 after which agriculture primarily started to follow a latifundiary monoculture model.

The idea that ecosystem processes must provide products necessary for human survival is dangerous since it makes room for individuals to understand that one can enjoy and interfere in processes that took thousands of years to exist in harmony on our planet. Conservationists and ecologists may see ecosystem management for agricultural purposes as an irreversible interference in natural processes. On the other hand, ecological engineers see changes caused by agriculture in the ecosystem and its services as a means of preserving the natural system and, at the same time, providing provisioning services. Thus, the core question appears to be: can there be a middle ground between the two approaches? In other words, is it possible to manage ecosystems so that all their ecological processes – if well investigated, interpreted, and understood – can be considered ecosystem services (excluding the idea that there are ecological processes acting as disservices to agriculture)?

In light of the current scenario, according to which food production accounts for approximately 69% of greenhouse gas emissions, 70% of freshwater use, and the annual loss of approximately 6 million hectares of agricultural areas due to soil desertification processes [42, 43], it is necessary to manage ecosystem services to provide food of the right amount and quality to the population without generating irreversible environmental burdens. From the moment when a given human activity starts imposing negative “feedbacks” on the population, this activity becomes unstable in the long term and may eventually destroy the population itself [44].

Читать дальше