Suppose I have made the three kinds of Karma, good, bad, and mixed, and suppose I die and become a god in heaven. The desires in a god body are not the same as the desires in a human body; the god body neither eats nor drinks. What becomes of my past unworked Karmas which produce as their effect the desire to eat and drink? Where would these Karmas go when I become a god? The answer is that desires can only manifest themselves in proper environments. Only those desires will come out for which the environment is fitted; the rest will remain stored up. In this life we have many godly desires, many human desires, many animal desires. If I take a god body, only the good desires will come up, because for them the environments are suitable. And if I take an animal body, only the animal desires will come up, and the good desires will wait. What does this show? That by means of environment we can check these desires. Only that Karma which is suited to and fitted for the environments will come out. This shows that the power of environment is the great check to control even Karma itself.

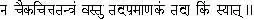

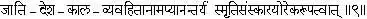

9. There is consecutiveness in desires, even though separated by species, space, and time, there being identification of memory and impressions.

Experiences becoming fine become impressions; impressions revivified become memory. The word memory here includes unconscious co-ordination of past experiences, reduced to impressions, with present conscious action. In each body, the group of impressions acquired in a similar body only becomes the cause of action in that body. The experiences of a dissimilar body are held in abeyance. Each body acts as if it were a descendant of a series of bodies of that species only; thus, consecutiveness of desires is not to be broken.

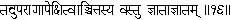

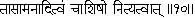

l0. Thirst for happiness being eternal, desires are without beginning.

All experience is preceded by desire for happiness. There was no beginning of experience, as each fresh experience is built upon the tendency generated by past experience; therefore desire is without beginning.

11. Being held together by cause, effect, support, and objects, in the absence of these is its absence.

Desires are held together by cause and effect; (The causes are the “pain-bearing obstructions” ( II. 3) and actions ( IV. 7), and the effects are “species, life, and experience of pleasure and pain” ( II. 13). — Ed.) if a desire has been raised, it does not die without producing its effect. Then, again, the mind-stuff is the great storehouse, the support of all past desires reduced to Samskara form; until they have worked themselves out, they will not die. Moreover, so long as the senses receive the external objects, fresh desires will arise. If it be possible to get rid of the cause, effect, support, and objects of desire, then alone it will vanish.

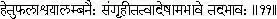

12. The past and future exist in their own nature, qualities having different ways.

The idea is that existence never comes out of nonexistence. The past and future, though not existing in a manifested form, yet exist in a fine form.

13. They are manifested or fine, being of the nature of the Gunas.

The Gunas are the three substances, Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas, whose gross state is the sensible universe. Past and future arise from the different modes of manifestation of these Gunas.

14. The unity in things is from the unity in changes.

Though there are three substances, their changes being co-ordinated, all objects have their unity.

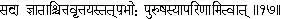

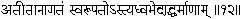

15. Since perception and desire vary with regard to the same object, mind and object are of different nature.

That is, there is an objective world independent of our minds. This is a refutation of Buddhistic Idealism. Since different people look at the same thing differently, it cannot be a mere imagination of any particular individual.

(There is an additional aphorism here in some editions:

“The object cannot be said to be dependent on a single mind. There being no proof of its existence, it would then become nonexistent.”

If the perception of an object were the only criterion of its existence, then when the mind is absorbed in anything or is in Samadhi, it would not be perceived by anybody and might as well be said to be non-existent. This is an undesirable conclusion. — Ed.)

16. Things are known on unknown to the mind, being dependent on the colouring which they give to the mind.

17. The states of the mind are always known, because the lord of the mind, the Purusha, is unchangeable.

The whole gist of this theory is that the universe is both mental and material. Both of these are in a continuous state of flux. What is this book? It is a combination of molecules in constant change. One lot is going out, and another coming in; it is a whirlpool, but what makes the unity? What makes it the same book? The changes are rhythmical; in harmonious order they are sending impressions to my mind, and these pieced together make a continuous picture, although the parts are continuously changing. Mind itself is continuously changing. The mind and body are like two layers in the same substance, moving at different rates of speed. Relatively, one being slower and the other quicker, we can distinguish between the two motions. For instance, a train is in motion, and a carriage is moving alongside it. It is possible to find the motion of both these to a certain extent. But still something else is necessary. Motion can only be perceived when there is something else which is not moving. But when two or three things are relatively moving, we first perceive the motion of the faster one, and then that of the slower ones. How is the mind to perceive? It is also in a flux. Therefore another thing is necessary which moves more slowly, then you must get to something in which the motion is still slower, and so on, and you will find no end. Therefore logic compels you to stop somewhere. You must complete the series by knowing something which never changes. Behind this never-ending chain of motion is the Purusha, the changeless, the colourless, the pure. All these impressions are merely reflected upon it, as a magic lantern throws images upon a screen, without in any way tarnishing it.

Читать дальше